An industrial designer’s unexpected view on plastics

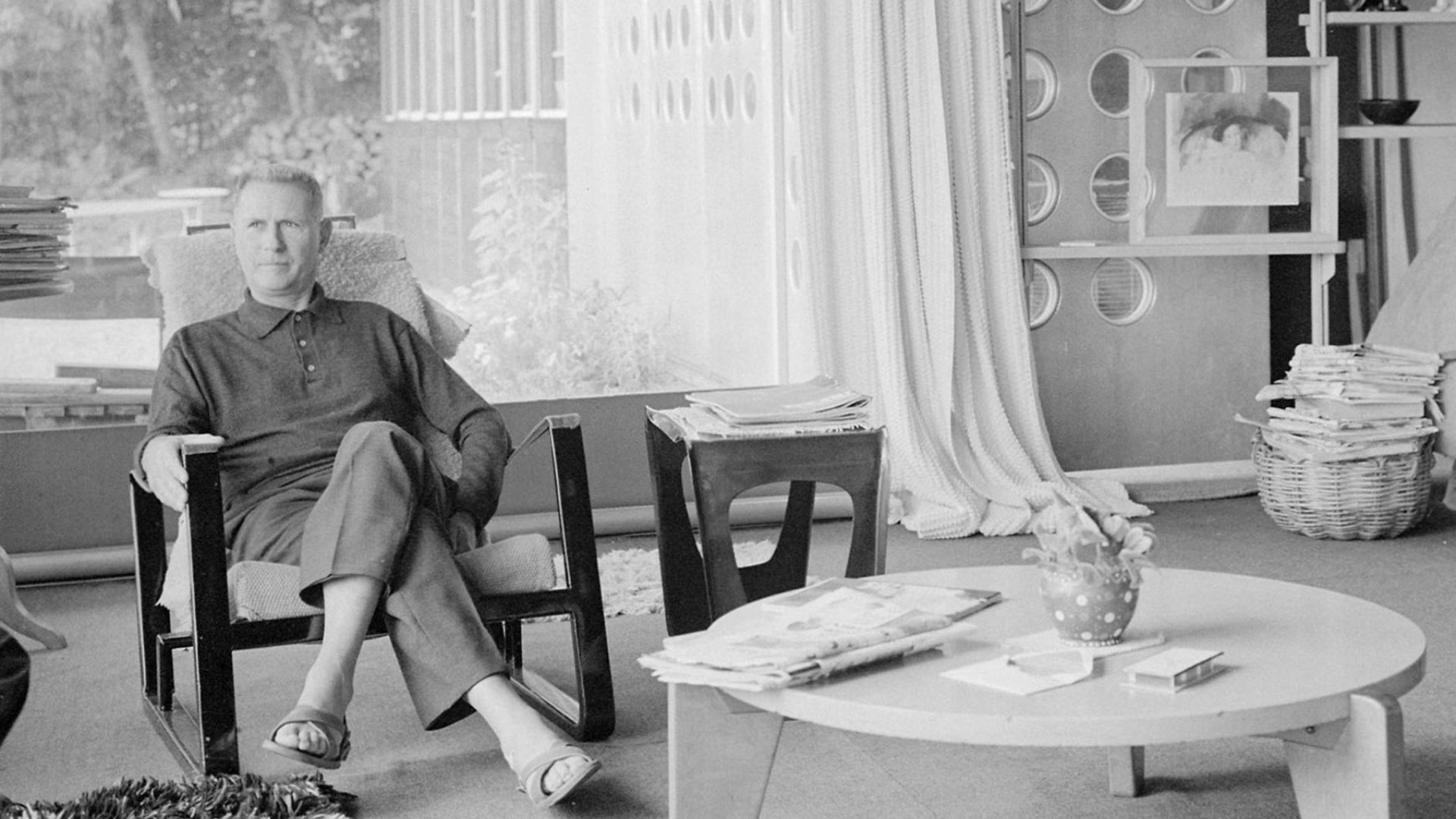

Odo Fioravanti works as an industrial designer since 1998 and opened his studio in 2003.

Since then, he earns his living on royalties: the chairs he has designed for Pedrali sell in millions.

Some of them (like Snow, one of the first ever monoblocks chairs manufactured with gas-aided injection molding) are made of plastic, a material that he knows intimately, in its good and bad aspects, which he shared with us.

Because, like he says in this interview, “there is a great future for designers who understand the key issues of sustainability and a somber one for those who just surf superficially on global crusades, even if well-meant”.

Plastic is seen as evil. Is it?

Odo Fioravanti: “The crazy use of plastic is abysmal, obviously.

But now we are in panic mode and most people make no distinctions.

I work in the furniture design industry and in my field all companies now respond to this panic by providing seemingly relevant solutions.

For instance by stating they use recycled plastic or that their plastic products are 100% recyclable.

Or, again, by trying to reduce the amount of plastic they use.

These strategies would all be good if they were true (most of the time, they aren’t if you read between the lines).

But my point is: they require costly and long processes to implement at industrial level which may not be worth it.”

Do you mean using plastic in the design industry is ok regardless?

Odo Fioravanti: “No. I am saying that it all depends on what you do and how you do it. How much plastic actually gets to the dump comes from well-designed furniture?

No-one has ever seen a branded designer chair abandoned on a beach: if it was, it would be immediately collected and re-used.

While food and beverages packs are everywhere and no-one collects them.

Yet, following the crusade against plastic that allows no distinctions, the design community, especially young designers, seems obsessed with alternatives to plastic.

The so-called bio-materials.

It makes total sense to experiment with them, obviously, if you are designing a disposable packaging.

If you want to make a difference as a designer, though, you should realize that your best take is on making things last.

For instance by designing a correct, timeless form that will not go out of fashion quickly rather than make them bio-degradable.

And use single materials with a “design for disassembly” approach so that separate waste collection and recycling is a real option.

Good quality plastic, in these cases, can be a very valid option”.

How hard is it to reduce the amount of plastic used in a product?

Odo Fioravanti: “It is very hard, and sometimes it’s actually a less sustainable option.

Take for instance the Monobloc, the typical cheap white plastic chair sold world-wide by the millions.

It uses less plastic than a designer chair and it is very light yet it breaks and doesn’t last because it’s made in the cheapest possible way. It’s like a throw-away object.

In such a case, a slightly heavier chair that is sturdy and also – allow me – more pleasing to the eye is a much more sustainable choice.

Because the issue is durability which is at the heart of the Reuse strategy.

Which is the least impactful in environmental terms (not by chance, the 3Rs of the circular economy are ordered as Reuse, Reduce, Recycle)”.

Most design companies now focus on using recycled plastic. What’s your take on that?

Odo Fioravanti: “Most of what is said to be 100% recycled, in the design industry, isn’t (also because are no independent, government-related bodies that go out and verify such statements).

If you use truly recycled plastic and nothing else, you will get a brown or gray substance.

So unless your item features one of those colors, it has a certain percentage of new plastic.

Furthermore when you make a chair with recycled plastic and you want a certain quality – which you need in order to make it durable – you have to use production waste: plastic that comes from molding other items that hasn’t been used or exposed to the sun and rain.

So yes it’s recycled but it’s not tackling the issue of left-over plastic from throw-away packaging – which is the real problem, world-wide.”

What about recyclability?

Odo Fioravanti: “In theory, all plastic is recyclable as long as it doesn’t contain other materials.

So you could make a chair out of high quality secondary plastic, sell it and then recycle it to make a new one.

But this circle only works if you have a system in place by which the owner gives back to the company the chair after its end of life, so that the proper technology can be used in a specifically designed system and give life to another similar chair.

This presents two issues.

First of all, the new chair – if truly made only with used recycled plastic – will never have the same quality as the first one. Secondly, how do you deal with the logistics to make it economically sustainable?

If you are in the US and you sold 2000 chairs in South Africa to 20 big clients: the costs of sending the chairs back should be charged to the client, to the retailer, to you? How much is the shipment going to cost, in carbon footprint terms?

In most cases, today, recycling costs are charged to local governments, hence to all citizens because customers just bring items to the local dump.

Which is unfair on the collectivity and doesn’t result in proper re-use of the secondary material.”

It all sound a bit hopeless…

Odo Fioravanti: “Quite the opposite. It’s very challenging for designers.

For those who understand Life Cycle Assessment, those who figure out when you should use plastic and when you should certainly stop abusing it, those who reject a signature style and fancy shapes and embrace good, long lasting design, those who will be able to define the services and the processes to address the issues related to recyclability… “

What should a designer know about plastic in order to work with it in the best possible way?

Odo Fioravanti: “It’s important to keep in mind that this is a complex material whose behavior, even when you are very experienced, is hard to predict in total. This is because of some inherent characteristics of plastic.

- Plastic cuddles up on itself

The first one is that it tends to cuddle up on itself, like a ball, when it cools down: which means that you must find ways to keep it in place when it starts deforming as you take it out of the mold.

Once you figure out in which way it deforms you can design against it although this also goes as a trial and error process.

Because what can happen is that if you change an angle even very slightly plastic curves in one or the other way: it’s all a matter of finding the perfect balance and it can take time and effort.

- Plastic loves even thickness

The second characteristic of plastic is that it loves to be at a constant thickness so that the heat is evenly distributed.

If you have a full leg, ie one with no hollow inside, while the outer part cools down the inner one keeps the heat and thus starts deforming.

Which is why making a plastic chair, legs included, in a single mold has been a challenge for years.”

Yet we see many plastic chairs with thick legs…

Odo Fioravanti: “They are either made with two molds and then assembled or manufactured with gas-aided injection molding.

This is actually the technology that I grew fascinated with as a student and which led me to design and produce my Snow, my first chair with Pedrali and one of the very first ones ever made with gas-aided injection molding.”

“Monoblock plastic chairs have been a challenge for years due to the cost of a large mold and the issue with the deformation of full legs that we just discussed.

In 1967, Vico Magistretti came up with a solution: an S-shaped leg, similar to a curved sheet of paper, that would guarantee the sturdiness while retaining the same thickness all along its surface.

It was applied on the chair Selene, produced in 1969 after 2 years of work with the Artemide technicians.

It was only in 2000 that Magis applied to the Air Chair by Jasper Morrison the new gas-aided technology to monoblock plastic injection molding: this works by forcing gas into the central part of the leg in the mold so that a hollow element is created the external part – the one that is stuck to the steel of the mold – remains and hardens.

So, you see, changing the rules of the game, when it comes to plastic, is not as easy as it seems.

There are lots of variables to keep in mind.”

What should young designers consider when it comes to plastic?

- Odo Fioravanti: “They should definitely know all the ins-and-outs of this material: the only way to do it is to actually see where plastic is molded and possibly follow some cycles.

- They should also figure out where there are risks of greenwashing, ie communicating fake or misleading information to consumers about products that they design. Designers should oppose this with all their might because once your name is mixed in something shady it will be very difficult to get it clean.

- They should also know what is technically possible to reduce the quantity of material used without compromising stability and results: again it’s a knowledge that you develop by doing.

- Last but not least, they should avoid extra-fancy aesthetics that don’t last. It’s always tempting to leave your signature on something you love. When you are tempted, keep in mind that there is a great future for designers who understand the key issues of sustainability and a somber one for those who just surf superficially on global crusades, even if well-meant”.