Insights on disability help designers design for all

Most products are designed by people who can move, see, experience objects and life with no issues whatsoever for people who are the same as them.

Every industrial designer should experience a disability of some sort. It sounds like a harsh way to learn. Yet if it came to be, many problems related to accessibility and ease of use would never come to exist. This is why insights on disability are key to help designer design for all.

Most products, though, are designed by people who can move, see, experience objects and life with no issues whatsoever for people who are the same as them. Disability becomes central in briefs only when a team is designing very particular (often medical-related) categories of items.

Which, of course, doesn’t make sense: there is statistical certainty that a majority of the population will experience some form of disability at some point in their lives, with aging as the most likely cause. If disability affects everyone, why isn’t it naturally a part of our human-centered creative process? What positive change can occur if we make it so?

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

We asked Emily Siira, a professional industrial designer who also happens to be a person with disabilities. Emily applies her unique perspective in design practice every day.

What has been your career trajectory?

Emily Siira:

“I am currently an industrial designer at Milwaukee Tool, with a focus on the ergonomics of professional power tools. Previously, I worked at GE Healthcare, where I focused on patient experiences with medical equipment. Because of my personal background as a person with disabilities, universal design and accessibility are always front-of-mind when designing”.

How did disability shape your profession as an industrial designer?

Emily Siira:

“Prior to having a series of strokes at the age of 20, I didn’t have much awareness of the variety of disabilities which exist; I also had no idea that such a large portion of the world’s population is affected. Disability is universal because it can affect anyone at any point in life and statistically it will, whether by injury, disease, or components of aging; it is one of the only demographics which can be spontaneously entered by any person.

This is critical information to have as an industrial designer, because a significant portion of the users you’re designing for either are disabled, care for someone who is disabled, or will become disabled as their lives progress. Truly comprehensive design must consider the full spectrum of user experiences, and this includes the needs of people with disabilities.

Suddenly becoming disabled made me aware of this demographic while at the same time re-directing my career. I was originally studying engineering, and I shifted my focus to industrial design because I wanted to make a difference in the everyday experiences of others with disability-related obstacles like the ones I had faced”.

Awareness aside, why do you think considering disability helps design?

Emily Siira:

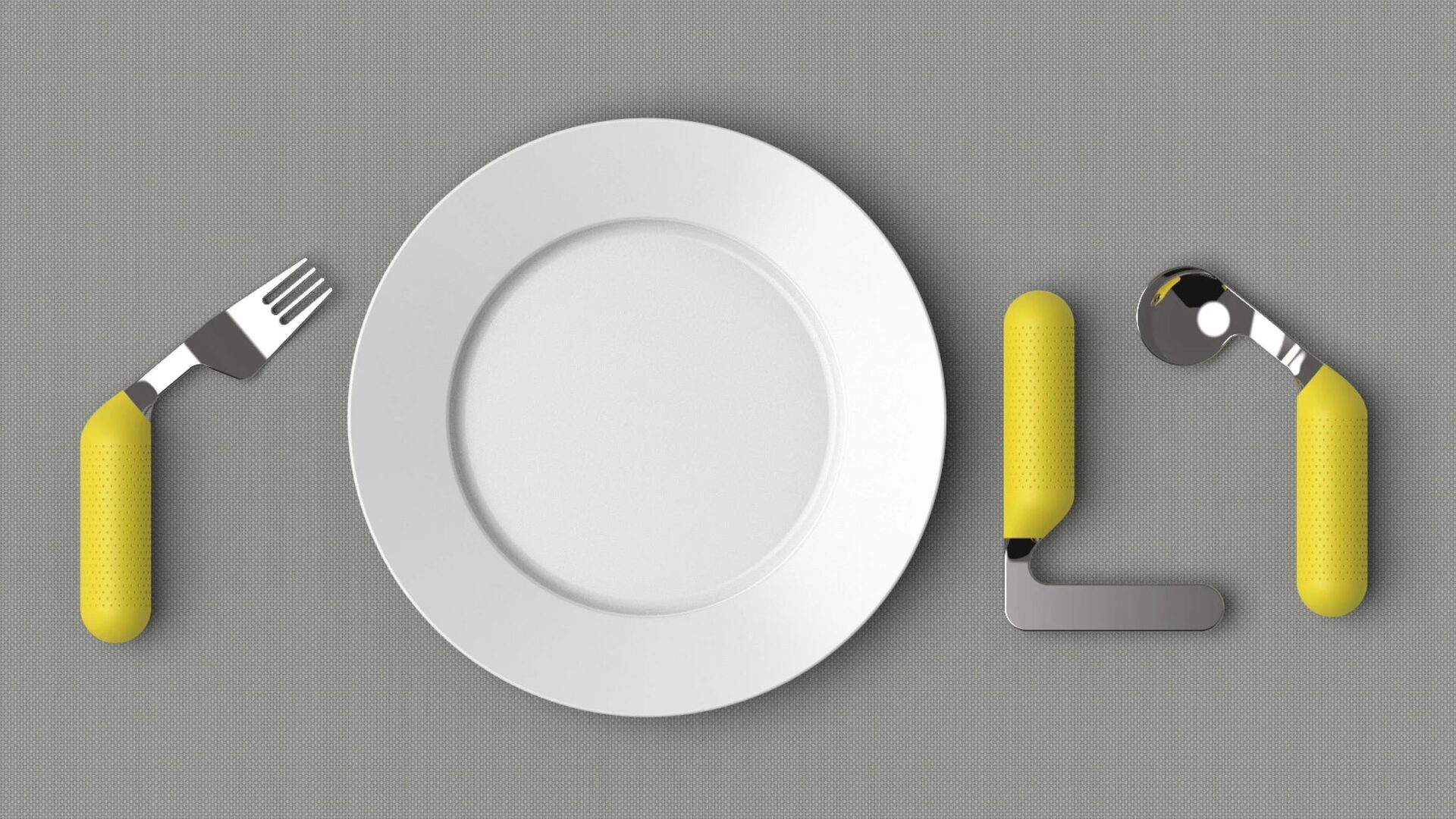

“It provides invaluable perspective. People with disabilities have a unique first hand understanding of the needs of a vastly under-represented and under-considered demographic. Referencing our background provides insight into unaddressed problems which need solving, while sharing our stories with other designers initiates the learning and empathy necessary to practice universal design.

People with disabilities are also expert problem-solvers, out of necessity. On a daily basis, we devise creative ways to navigate environments, systems and products which weren’t designed with us in mind.

Discovering these attributes sparked curiosity about how I could apply insight from living with disabilities to make future products and experiences more inclusive and accessible, and that is how I discovered the powerful intersection of disability & design”.

How do you channel your insights on disability into the design process?

Emily Siira:

“In essence, I am able to directly practice one of design’s primary mantras, which is to put yourself in a variety of users’ shoes, because I have years of hands-on experience with both neurological and mobility-related disabilities. When applicable to a project, I also make a point to share my story and make myself available to the team as a resource for research, insight, and ideas surrounding disabilities and human factors.

I of course cannot speak for all people with disabilities, and I have developed a network of people within this demographic who have a variety of perspectives. When I was working at GE Healthcare, I would interview a variety of other patients, technologists, and medical personnel to compare / contrast their thoughts with my own”.

How do you share your approach and insights with the design community?

Emily Siira:

“My current approach is multi-faceted, and it continues to evolve the more I apply it in the design world. Whenever possible, I strive to help other designers become familiar with the network of people with disabilities that I have developed.

In addition to practicing as a designer, I serve as an in-house connection to these necessary perspectives, which streamlines phases of the design process which involve human factors, user research, feedback, and testing.

I also connect online with a group of other designers who have disabilities. This group has become increasingly involved with IDSA (Industrial Designers Society of America) and its Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives.

IDSA has broad visibility within the Industrial Design profession, and we have been able to host and share articles, speaker panels, events, and resources to a large audience of designers through the channels of this organization”.

The goal of these efforts is to generate awareness, learning, and empathy surrounding disability and accessibility within our field, which will contribute to more universally inclusive and accessible design.

How should designers approach disability in their creative process?

Emily Siira:

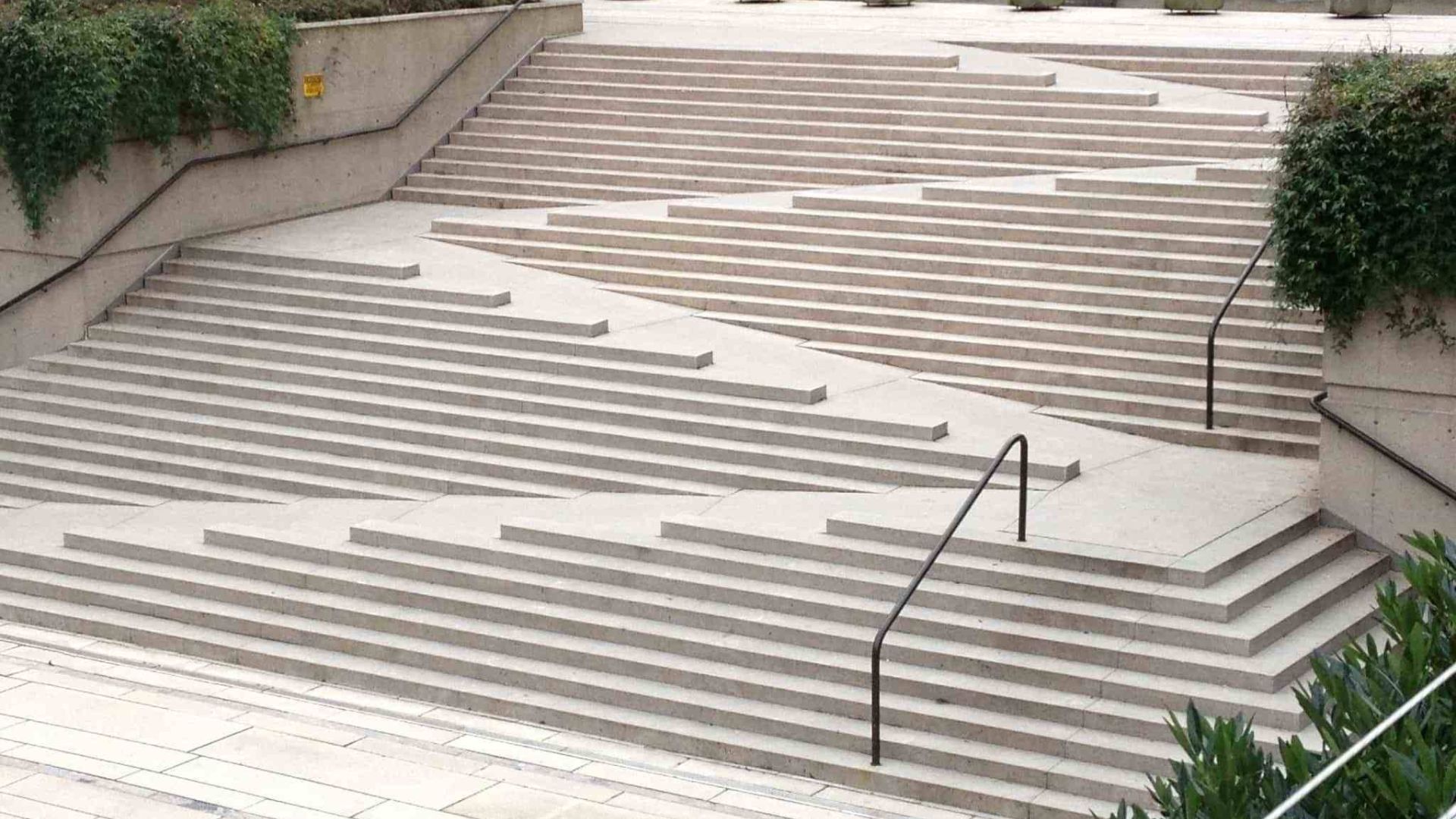

“Industrial Design is a human-centered profession that has the potential to ignite significant change and equity for the disabled community through the incorporation of inclusive design practices. Despite comprising such a significant portion of the world’s population, individuals with disabilities overwhelmingly perceive themselves to be unseen and overlooked with regard to the products, spaces, and interactions encountered in daily life.

People with disabilities are eager to help designers solve this problem! Many of us are open about our situations; all that’s needed is to hear us and include us. Involve us and our perspectives in your design practice, and it’s guaranteed that you will learn something new which can improve experiences for many peripheral demographics;

you’ll also walk away with strengthened allyship to a group which might very well control a quarter of your market’s purchasing power. Participatory design is key to achieving universal and accessible solutions.

To be effective, this process must involve all sectors of a product’s potential user demographic, including those assumed to be marginal; people with disabilities are often assumed to be so, yet the opposite turns out to be statistically true”.

How do you include disability-related input in the design process?

Emily Siira:

“In short:

1. INVOLVE: Involve people with disabilities early in the research / investigation phases of the design process, as we have unique power to reveal undiscovered problems which need solving.

2. PRIORITIZE: Prioritize the feedback of people with disabilities on aspects related to ergonomics and human factors, since we have increased sensitivity to these considerations. Weigh feedback from people with disabilities the same as any other demographic in product testing.

3. DON’T MAKE ASSUMPTIONS: Never, as a non-disabled person, make assumptions about the needs and opinions of people with disabilities; anything but direct input is purely conjecture”.

Is design the best discipline to improve the lives of people with disabilities?

Emily Siira:

“Designers can certainly be powerful stakeholders in this. Empathy is in our job description, from a standpoint of understanding the user. In my experience, designers make excellent allies to the disabled community because they’re a group driven to learn and understand by nature and by training.

Some of the greatest support that can be offered to the disabled community is akin to the design process we already know; listen, learn, and adapt. If a person opens up about a disability or other factors of diversity in their life, they are taking a chance by exposing a very personal side, because they feel that the benefits outweigh the risks for impactful collaboration and design.

From an interpersonal standpoint, it’s important to apply the same empathy and insights on disability used in design practice to everyday interactions with everyone, not just those you know to be in the disabled community. Many disabilities and other life challenges are invisible, and it’s impossible to know what someone is experiencing behind the scenes. Broadening understanding with new and different perspectives will only benefit design practice, which will result in better products and experiences for all!”.