A contemporary look at Jean Prouvé’s heritage

There is a lot that designers today can learn from Jean Prouvé’s approach.

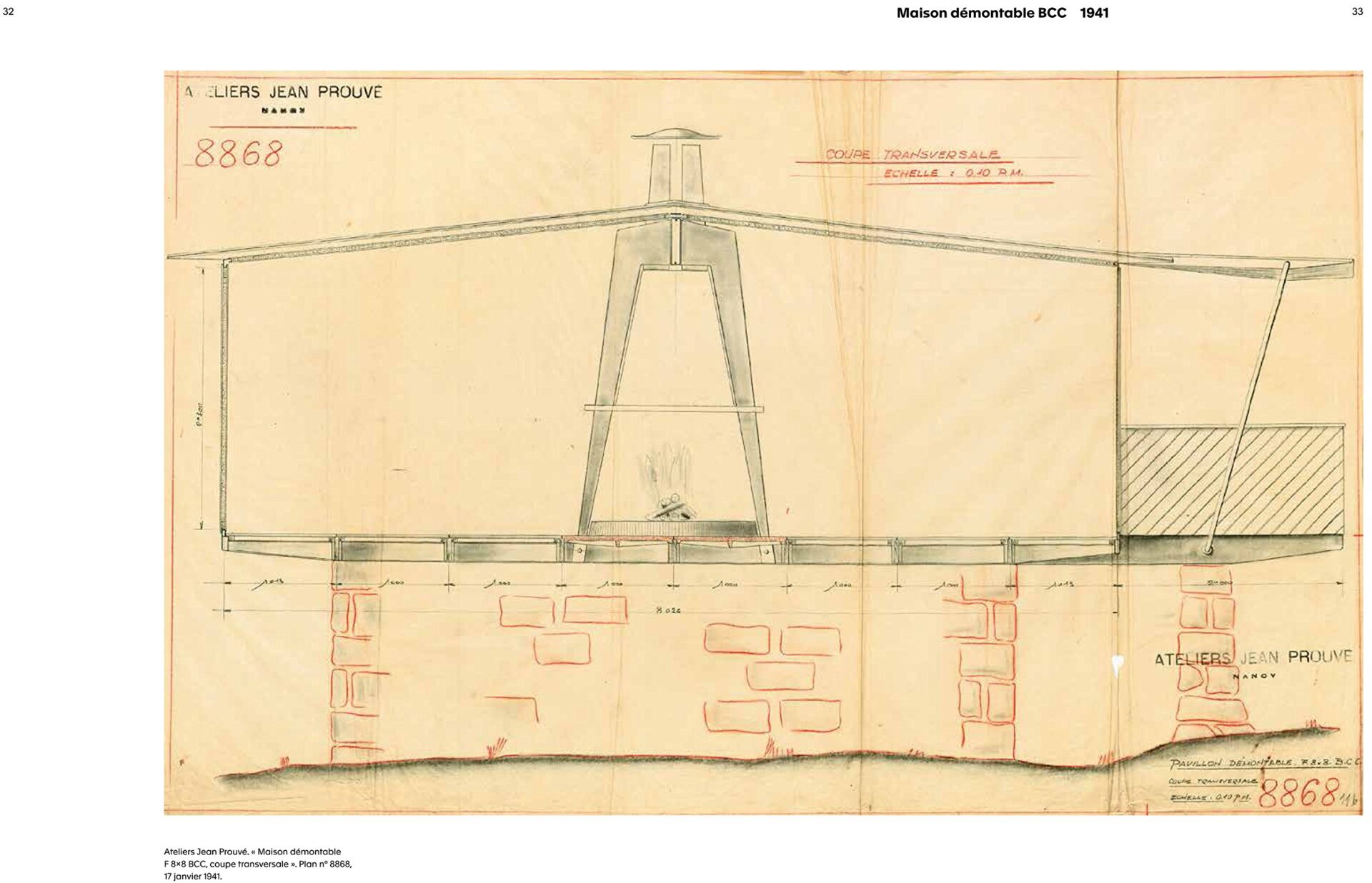

The French designer and architect (1901-1984), educated as a blacksmith and gifted with an engineering mind, has authored some of the most iconic pieces of furniture, namely the Standard Chair (in production with Vitra), and disruptive architectures, such as the Tropical House (inexpensive, ready to assemble home to transport to French African colonies engineered in 1949).

If you don’t know who he was, here a useful biography.

Jean Prouvé’s design is still very much appreciated today: his pieces are best-sellers and featured on most home styling magazines. But beyond the global accolade by interior enthusiasts, there are actual reasons why his work should still be considered central by product designers of this day and age. And that is related to the fact that

his design approach is perfectly suitable to face contemporary issues.

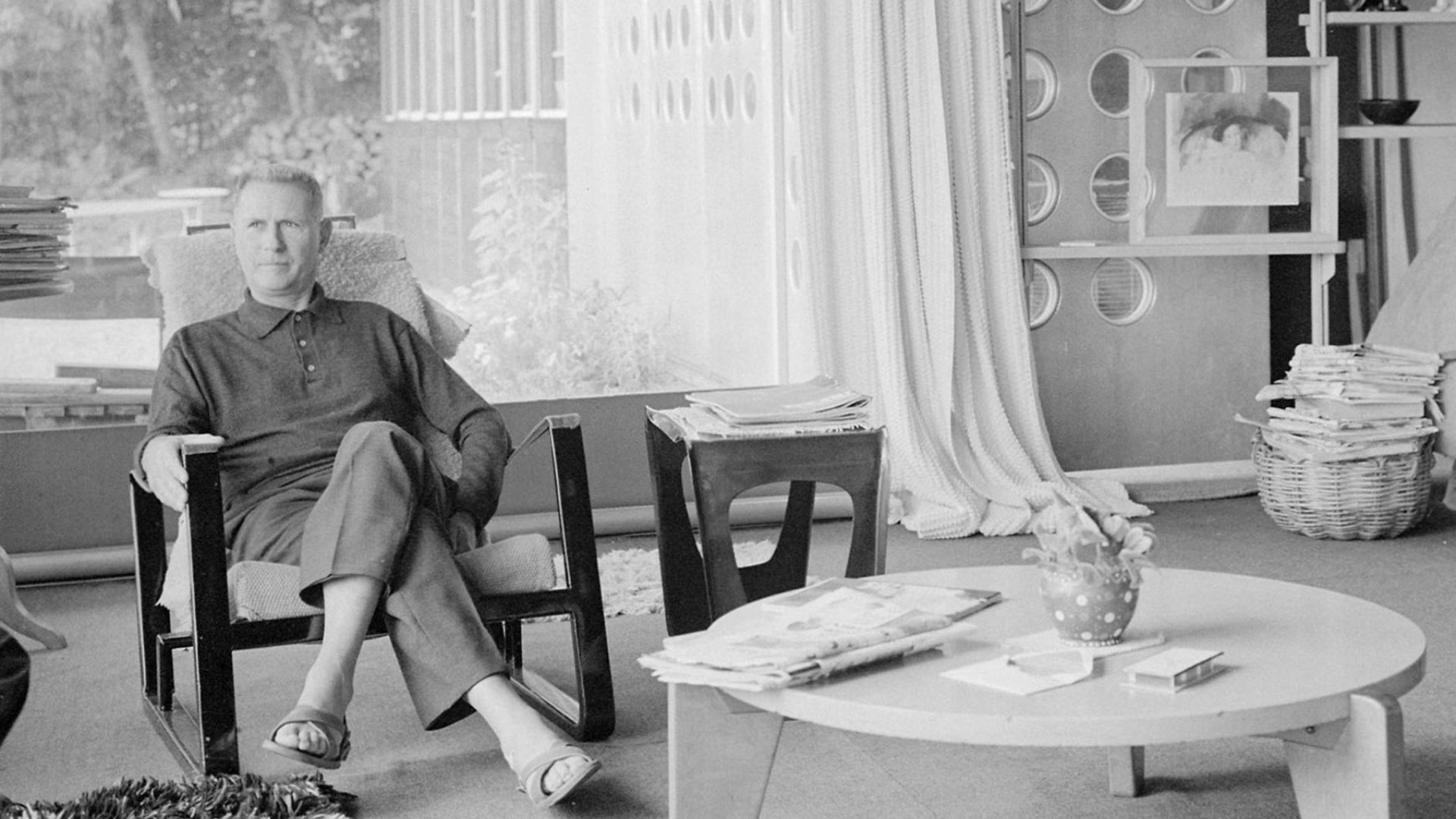

We spoke to Stine Liv Buur, a scholar who manages the Classic Collections at Vitra (the owner, Rolf Fehlbaum, is the greatest collector of Jean Prouvé’s work). Buur has studied Jean Prouvé’s work extensively, in partnership with the Jean Prouvé Foundation.

She helped us single out 5 key points to Jean Prouvé’s design:

- He knew materials intimately

- He used locally available materials

- He wanted to show how objects function

- He knew when to stop designing

- He lived as part of the community that he designed for

Let’s now see

how these key points fit in the contemporary designer’s toolkit.

1. Jean Prouvé knew materials intimately

When we say Jean Prouvé was very close to materials we mean he actually worked with them with his own hands.

Jean Prouvé was trained as a blacksmith in Paris: he learnt modern metalworking and welding techniques under the wrought-iron craftsman Szabo and was extremely skilled at it.

“He was in love with steel”, explains Buur. “Having worked the material for so long as a blacksmith, he instinctively knew what he could do with it, how he could use it to achieve new forms and functions”.

The knowledge you can get from working directly with materials is missing, according to Buur, in today’s educational paths.

“We use computers to figure out forces, shapes, resistances, and that’s great. Yet we have lost touch with materials in action. Very few young designers work materials with their hands, check out how they change as a response to what is done to them, observe how they behave. These are activities that, also because they occur through a longer time span than making a simulation, get more imprinted in our brains”.

“Working materials with your hands gives the emotional understanding that is needed to make relevant designs today”

And it is something that could be achieved by training in a hands-on studio or a craftsman’s workshop. It is not by chance that so many great furniture designers of today also trained as ebenistes.

2. Jean Prouvé used locally sourced materials

Amongst all metals, Jean Prouvé worked mainly with steel.

“This was because for Jean Prouvé everything started through physical experience and manual practice: and he knew that in order to know a material intimately, it needs to be readily available nearby”, explains Buur. “Steel, in particular, was widely available in the Nancy areas where Jean Prouvé was born and where he practiced”.

He basically applied a km-zero approach to materials which is very relevant today.

Beyond the obvious ecological implications, focusing on what’s around, on the materials that relate to one’s personal story would help today’s designers become experts: achieving a competitive vertical edge on a topic that is very close to home.

Something that both in the production arena as well as in the limited edition-galleries world is very much sought after.

3. He wanted to show how objects function

Jean Prouvé’s signature element is, indeed, the bent metal sheet: the so-called airplane-wing sheet.

“He didn’t appreciate the Bauhaus approach of using tubular steel because it hides the structural forces of objects. When you talk about a chair, the tube must have the same size throughout its profile – hence the strongest possible, to withstand the weight. But the weight, as we sit, is distributed in different ways and the designer could use less material where less force is applied”.

He, on the contrary,

wanted to show where forces were and use only the material that was needed.

It was experimenting with steel that he came up with the airplane wing shape: a sheet of steel that he bent and welded with another element to get to the required stability.

His love for designing honest objects, also drove him to show all connecting elements, keeping materials strictly separate:

everything in Jean Prouvé’s furniture is easily dismantable.

“This characteristic is key today, when design-for-disassembly is vital for promoting durability (to allow for repairs and eventually recycling”, says Burr.

4. He knew when to stop designing

“It took Jean Prouvé a decade to bring the Standard chair to perfection: which is using as little steel as possible, only where it’s required”, continues Buur.

Knowing when to stop designing is no easy task.

Prouvé mastered it because he had an engineering mind: searching for essentials and discarding useless extras. Having an artistic background (he grew up in the workshop of his dad, an acclaimed art nouveau painter) helped him keep a high aesthetic and emotional value in the objects he designed.

For Jean Prouvé

when an object achieves as much as possible with as little as possible, it is finished.

Doing so today is a challenge. Styling and overproduction force designers to push the limits. Being spotted on social media often means overdoing things and shouting out loud skills or exaggerations.

“Yet when you want to work with sustainability in mind – something we should all do now, imperatively – learning to stop designing is vital. A mental approach that designers should practice consciously, relentlessly”, says Burr”.

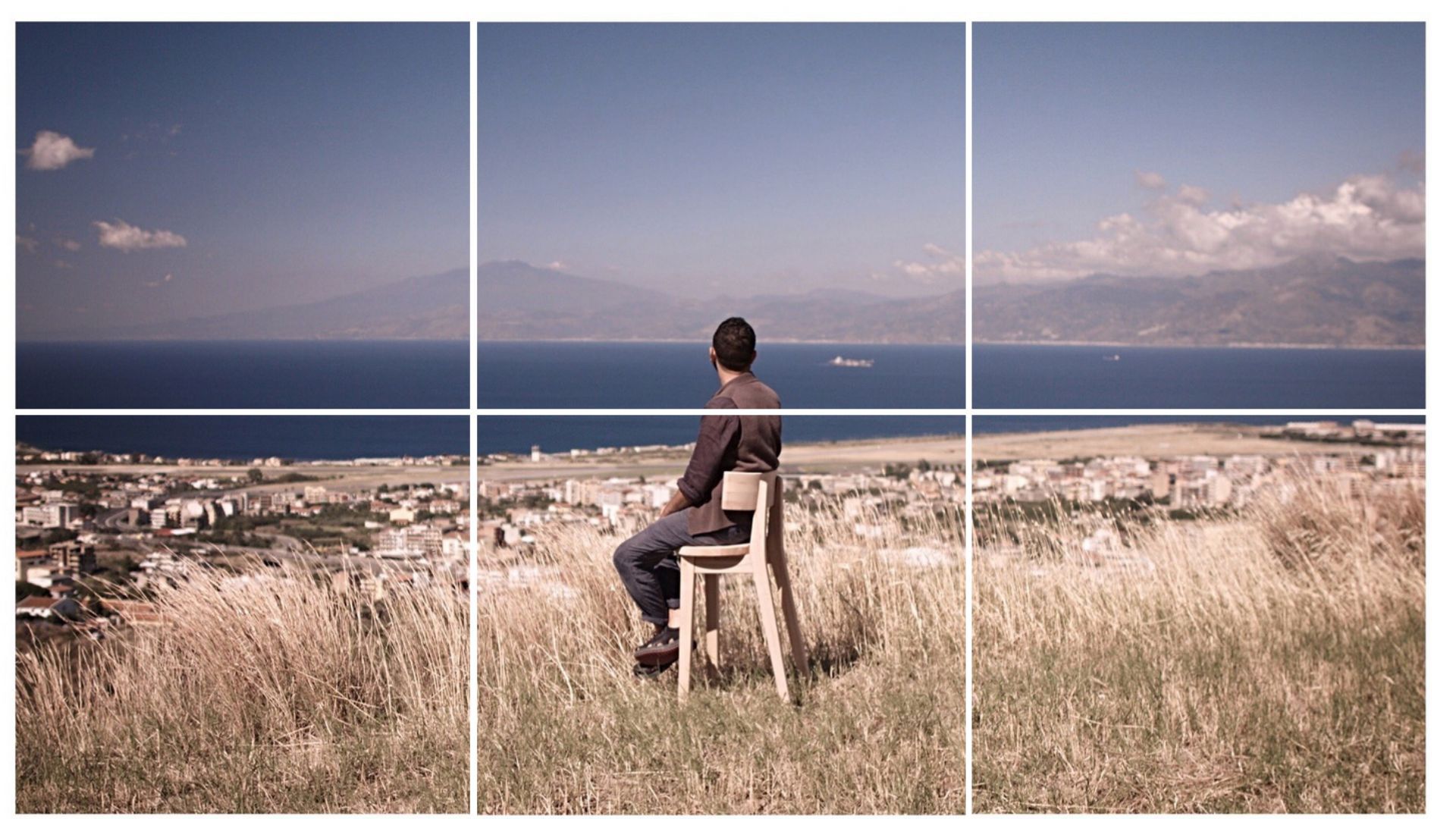

5. He lived as part of the community he designed for

This details of Jean Prouvé’s personality is particularly relevant for those who run their studio.

When Jean Prouvé got back to Nancy from Paris, he worked as a blacksmith and started making some furniture. He was basically alone and doing everything by hand or with very few machines, in a small workshop.

But after winning a competition to design the furniture for the Cité Universitaire de Nancy his business grew.

His Atelier Jean Prouvé was founded, he got many machines, employed a lot of people.

He was, basically, an entrepreneur running his own factory.

All employees of Atelier Jean Prouvé received the same wages: the same that he would also get.

All extra earnings were invested in machines and in the business.

We are used to thinking that this is a communist approach that destroys the individuals entrepreneurial spirit and desire to achieve greater objectives.

But in Atelier Jean Prouvé the results were opposite.

“Blacksmiths, steelworkers, architects, designers, engineers were all struggling to make things better because they felt as part of an overall community, pushing what machines allowed them to do to the very end of experimentation”, explains Burr.

Should design studios today choose to do the same?

Clearly, it all depends on how you do things. Do you flatten the hierarchy to push people down and control them or to allow them to truly feel part of one organism – the company – in which everyone has a vital part to play?

“Being an integral part of the community one lives in helps living a better life and can also teach you how to run your own studio as a community”, says Burr. “The Jean Prouvé experience witnesses what great results such approach can give”.

Results that highly depended on this

flat and egualitarian approach and communal commitment.

In 1949 Aluminium Français bought into the Ateliers Jean Prouvé with its subsidiary STUDAL given exclusive sales rights for all architecture-related pieces and changing the wages and responsibilities structure (while also imposing the use of aluminum over steel).

“In 1951, Jean Prouvé resigns as CEO of the company also due to disagreements related to the management approach and the forceful use of aluminum where not needed”, says Burr.

Without his vision and his approach, Atelier Jean Prouvé didn’t last for long and, in 1956, was turned into Ateliers de construction préfabriquée de Maxéville (ACPM), focusing solely on prefabricated architectural elements.