Circular architecture: can used PVC pipes become a beautiful façade?

Pretty Plastic is challenging how architecture thinks about its materials, reevaluating waste as a design resource to create unique and sustainable cladding tiles.

As the construction industry grapples with mounting plastic waste, Pretty Plastic has emerged as a pioneer in circular design for architecture. The Amsterdam based company transforms PVC construction materials into architectural cladding, proving that sustainability and aesthetics are not mutually exclusive.

With projects spanning from temporary pavilions to permanent municipal buildings, Pretty Plastic represents a fundamental shift in how designers and architects can approach both material sourcing and material selection.

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

At the heart of the company is PVC waste. The material is sourced from construction sites across the Netherlands and Belgium, collecting discarded window frames, gutters, downsprouts, and piping systems that would otherwise be destined for landfills or incineration. As most public recycling systems only tackle HDPE and PET plastics, it is essential for private companies to focus on the other thousands of kinds of polymers that currently do not have a second life.

PVC in particular is one of the harder plastics to recycle, as it contains chlorine derived from salt, along with many additives including stabilisers, plasticisers, and pigments that complicate the process. When melted down, PVC can release harmful chemicals if not properly stabilised. These challenges have relegated the material to landfills, despite it representing approximately 20% of all plastic produced globally.

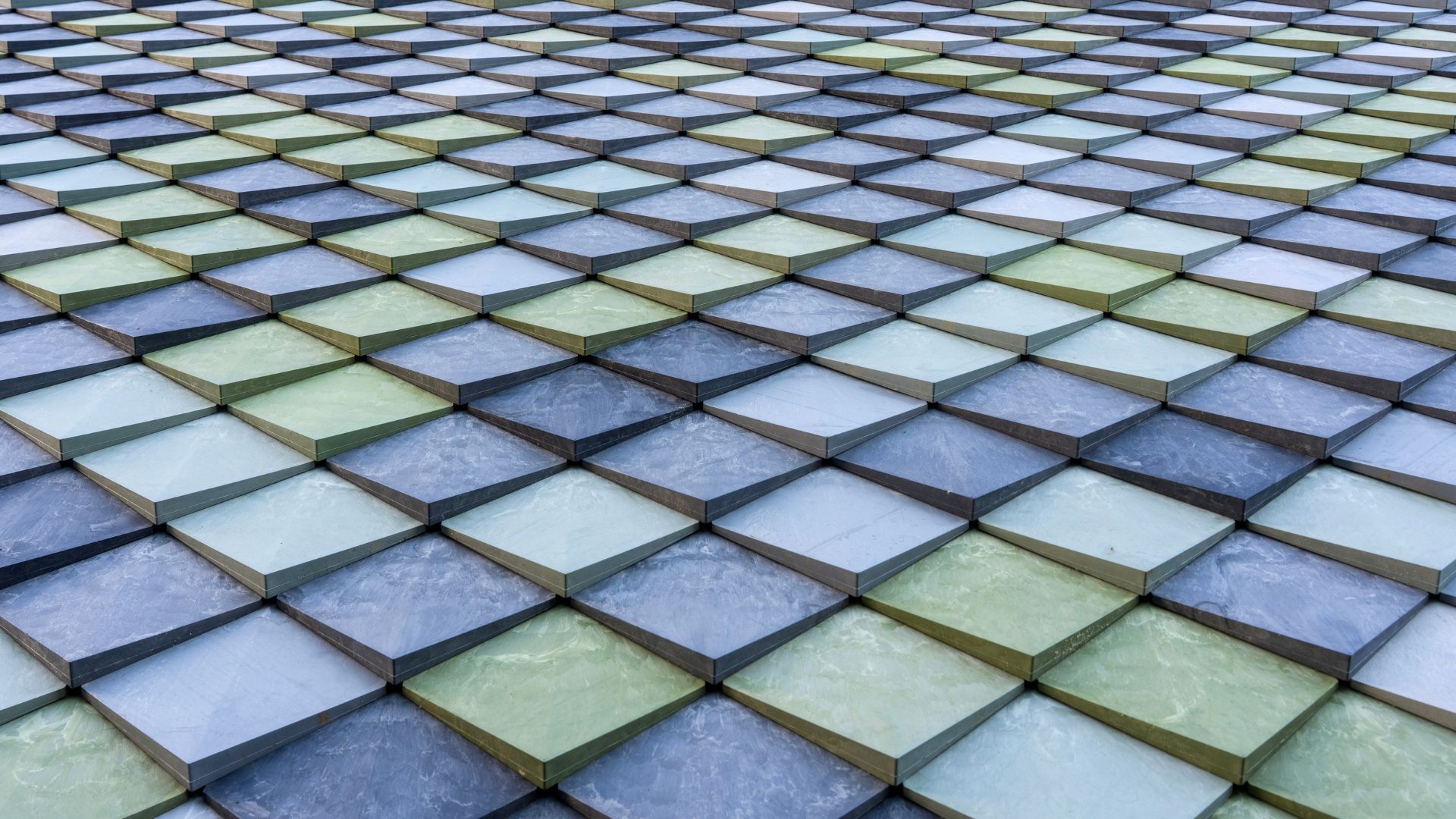

At Pretty Plastic, the tiles are manufactured through advanced injection moulding. Careful sorting of the waste by type and colour during collection creates the tiles’ distinctive marbled look, each one is unique, embodying the visual heritage of its previous incarnation. The production also achieves environmental efficiency, generating just 0.2 kg of CO2 per kg of material produced, in contrast with the 2.6 kg associated with virgin PVC.

The material’s architectural applications can be traced back to 2017, in the People’s Pavilion at Dutch Design Week in Eindhoven. Created by architects from Bureau SLA and Overtreders W, the temporary structure was built using 100% of borrowed materials, a statement for the emerging circular design path. The pavilion challenged conventional construction in every aspect: concrete foundation piles served as columns, steel rods from a demolished office building provided cross-bracing, and glass elements were borrowed from a greenhouse supplier and another demolished building. Everything was put together using industrial ratchet straps, no screws or glue were permitted, in order to disassemble the pavilion at the end of the event.

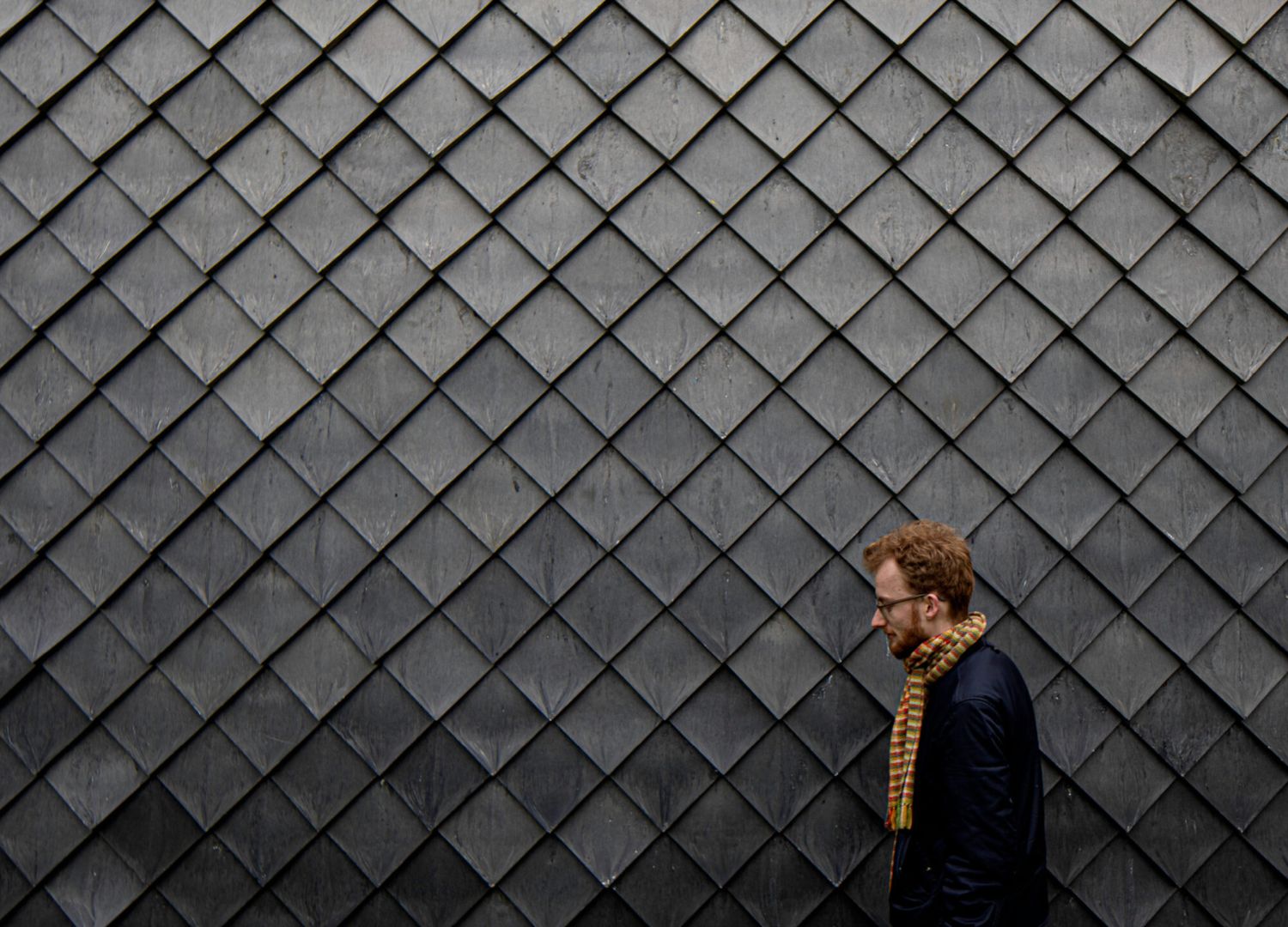

One of the company’s latest projects is MVRDV’s MONACO offices, a six-story structure developed for Rock Capital Group, planned to be completed during 2026. The building is made of two distinct architectural volumes, designed to express the duality between work and play. ‘Work’ is a cubic block clad in reclaimed bricks sourced from regional demolition, while ‘play’ is a dynamic façade clad in colourful Pretty Plastic tiles, in six shades of grey, green, and ochre in a fish scale pattern.

Despite the company’s success, significant challenges remain in scaling circular construction materials. For example, traditional Life Cycle Assessment methodologies prioritise minimising material usage, and can therefore disadvantage products like Pretty Plastic, which intentionally use more material to maximise waste diversion. This shows the tension between simplified sustainability metrics and the need for more nuanced frameworks that can account for specific scenarios.

Looking forward, Pretty Plastic continues expanding its product range with new colours, patterns, and tile designs, creating new creative possibilities for architects. By reimagining waste as a design resource, the company challenges industrial norms around material sourcing, aesthetic preferences, and environmental responsibility, offering a template for other future sustainable materials.