Art Director VS Design Curator

Fabio Calvi and Paolo Brambilla are Flos’ design curators.

A few years back, we would have seen the term art directors on their business cards but, together with Flos’ CEO Roberta Silva, they decided that this job title, imported from the art scene, was more suitable.

“It may seem pretentious”, they say, “but we had reasons to support this decision”.

These reasons are worth investigating and sharing within the design community:

- on one hand because they mirror a very contemporary way of managing creativity within a design-oriented company;

- and, on the other, because they provide an interesting insight into what producers truly look for in professional designers today.

What is the difference between an art director and a design curator?

Calvi Brambilla: “In the world of furniture and interiors, art directors are the professionals whom companies identify with: they give a direction for all collections, design most products and also direct and supervise communications in print, digital and stores.

This works perfectly for brands who go for a total style: which nowadays is most of them, especially when you think high end (B&B Italia, Cassina, Minotti, Flexform and so forth).

We differ very much from this approach in many ways.

We do not design lamps but select projects made by others that fit into the Flos’ brand positioning.

The brand does not go for a total look or style but aims to create as much variety as possible while retaining a Flos’ element to each project.

We are also responsible for the story that the company creates to bring all this to market.

So our role is very similar to that of a curator in the art world: someone who has a tale, selects artists and pieces to illustrate it and shares it with the world”.

The key seems to be the story. What are its ingredients?

Calvi Brambilla: “The common denominator of all Flos lamps is not related to style but how to how they are conceived and made: its design spirit.

The design spirit is something intangible that you feel when you interact with something.

In Flos’ case, it has to do with the attention to how light is emitted, to the high degree of technology used, to the relentless determination in revisiting product types and classifications: every product needs to go beyond what’s known somehow.

In the last few years, we have also developed a design-for-disassembly approach that ensures that all lamps need to be repairable, hence more long lasting”.

Is this approach more contemporary somehow or just more suitable to the lighting business?

Calvi Brambilla: “What is very contemporary in this approach is the fact that it’s a team effort.

Creatively speaking, Flos is directed by a steering committee that includes the CEO, the head of global marketing, the top engineers of the technical office and ourselves as design curators.

Most design focused companies actually work in this way but tend to be authored-centered when it comes to decision making.

Making decision making a shared and transparent responsibility and giving technology, marketing and design an equal weight through an overall curatorship is indeed a new thing which we feel mirrors contemporary times better than other management practices”.

Flos was a family company, now it’s in a large group: have these changes got to do with this?

Calvi Brambilla: “Yes, because these changes come with size.

When you are truly big you can no longer manage things by gut feelings,

however brilliant they may be and however romantic this notion can be.

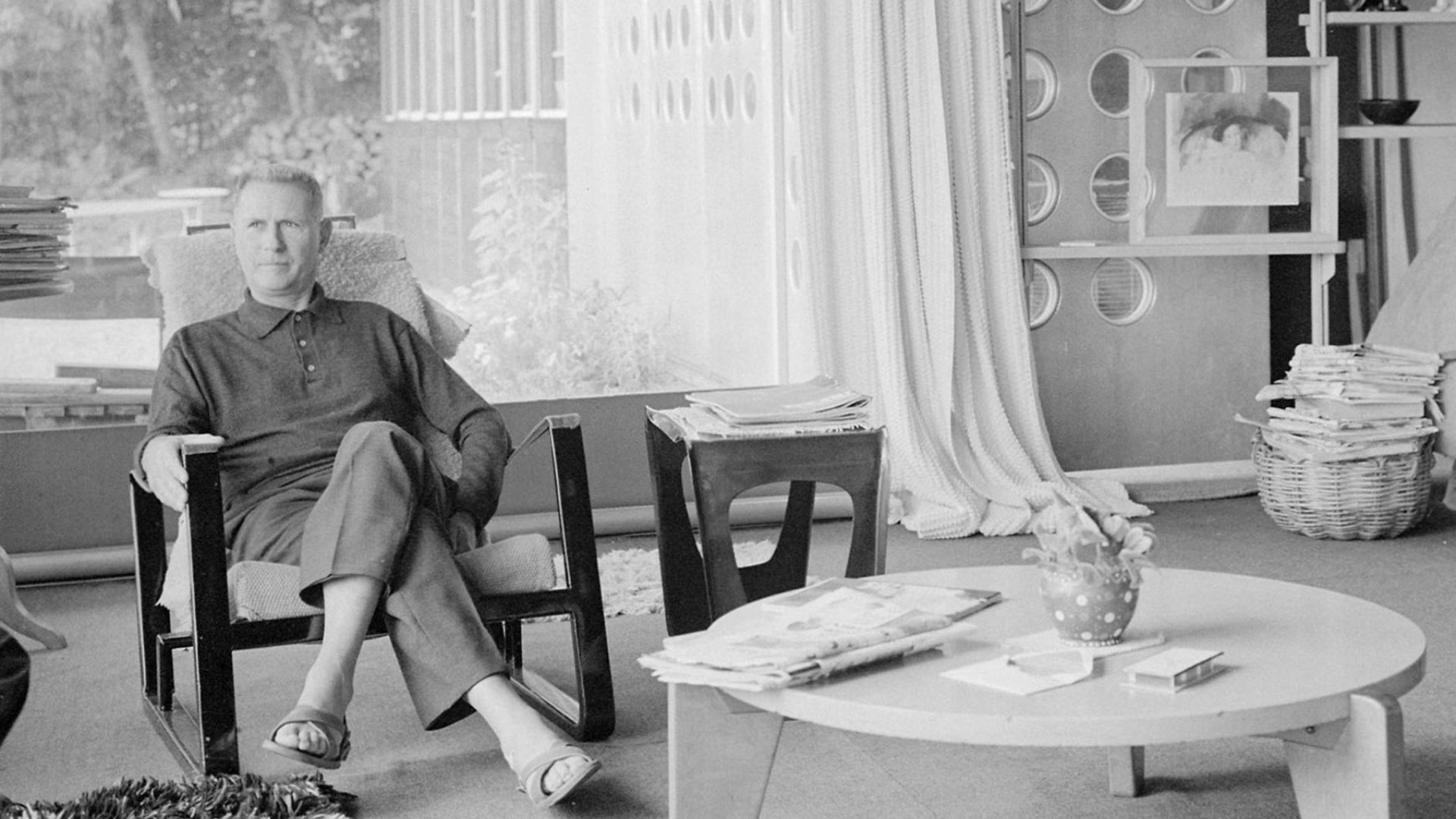

Flos was led for decades by visionary and extra-ordinary personalities: the founders Dino Gavina and Cesare Cassina first, then entrepreneurs Sergio and Piera Gandini, architects Achille Castiglioni and Tobia Scarpa, and finally Piero Gandini who brought Flos to its international standing and who was the overall decision-maker from the ’90.

But when you become a global brand you cannot rely on a single person’s view, however grand that is. Contemporary creativity, production and distribution requires stable and shared processes”.

What are the skills of a good design curator and how do they come to being?

Calvi Brambilla: “The greatest skill for a design curator is the capacity to see things from above, see the potential value in a variety of inputs, and think out of the box to mix it all creatively.

In order to do this, you need to go beyond the specialized approach that most Universities provide.

Mostly, you will learn this skill through personal growth and work experience. Focusing on how you do things rather than what you do”.

What are your suggestions towards young professionals to go about this personal growth?

Calvi Brambilla: “The main ingredients are a sincere passion for design, a relentless drive to deepen knowledge beyond what’s widely offered, a child-like curiosity towards everything.

Basically you have to consider your personal education as your own responsibility and be creative with the way you go about it.

Most product designers are for instance collectors of objects: physical items or catalogues, where – by putting information together – one can get to understand the actual history of how they came to being.

What is important for designers to know is not what is openly communicated by brands but what’s hidden: how things really came to being, figuring out which dynamics generated certain results, understanding that some masterpieces were actually generated by mistakes.

Another key learning is to do away, as soon as possible, with the idea of the genius creator: everything works better in teams and being able to respect other people’s knowledge is fundamental.

At the same time, other creative worlds – think art or fashion – are also an endless stimulus for designers.

Merging disciplines and influences is vital to creative industries and still not so many people can do it.

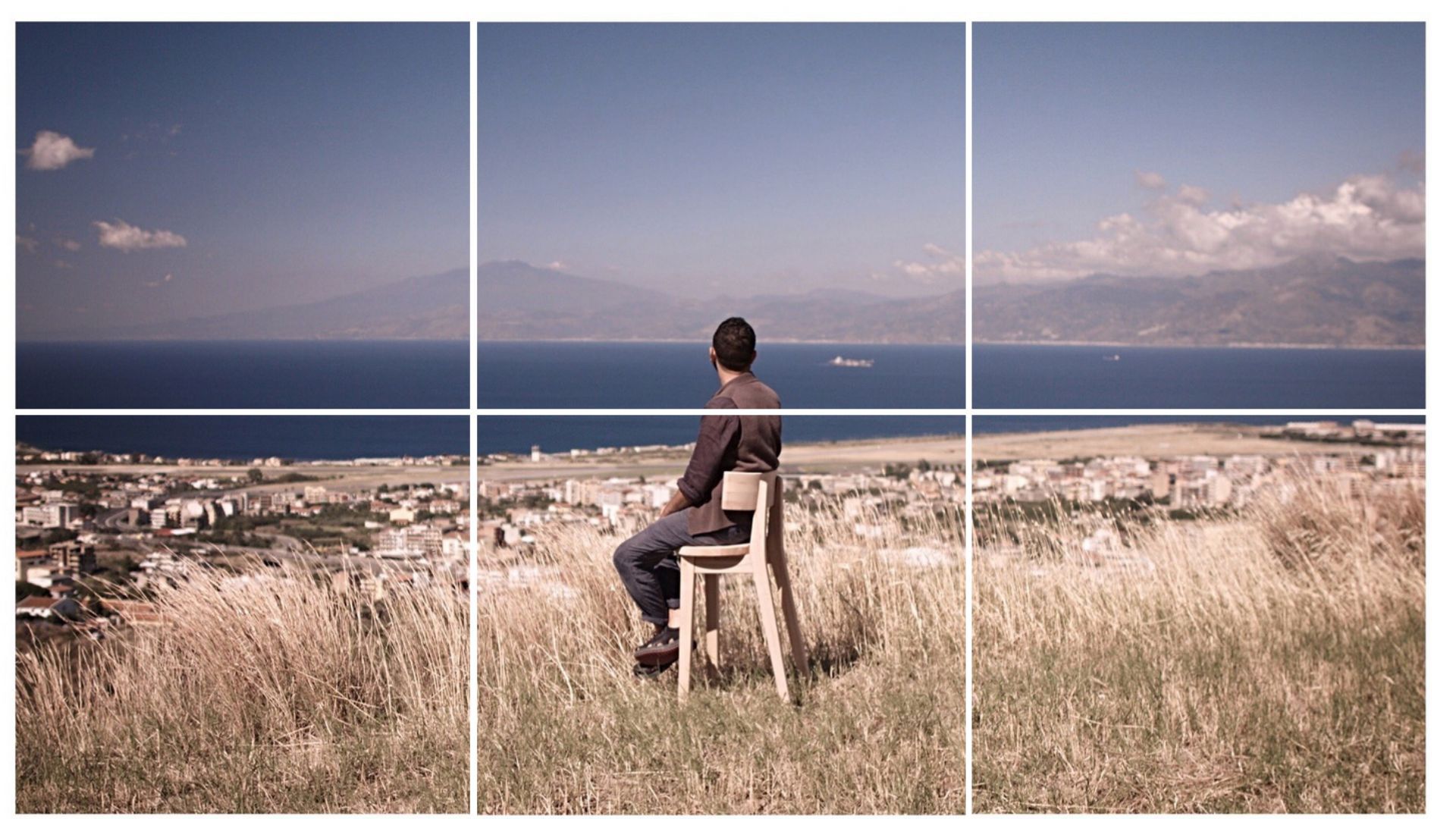

© FLOS, Skynest by Marcel Wanders – ph Francesco Caredda

The good news for young designers is that the tools to do this are nowadays at everyone’s fingertips: most information is accessible online if you know how to go beyond the surface.

The bad news is that what’s required in such an abundance is the capacity to isolate what matters: and that comes from personal knowledge which you can only build with time.

Patience is a very rare quality but still a very important one. Now perhaps more than ever”.

If you learn on the job, what is the best one to have if you aim at becoming a design curator?

Calvi Brambilla: “In our case what did it was our work for Flos as exhibition and booth designers.

But, again,

what matters is not just what you do but how you do it.

When you design the set that the company will use to show its products you need to know them intimately and find ways to make them shine, while at the same time creating a compelling overall story in which they all somewhat fit.

Many designers cannot help putting a signature style in their interiors and that is also a valid approach but one that we never pursued.

We are real design-addicts, in awe in front of things and how they are made, and always focus, when we design a booth, in giving objects (rather than ourselves) the central role.

Tackling booth design with a sincere passion for objects and for the history of a brand gives a designer an amazing head start to turn, one day, into design curatorship”.

You also talent-scout for Flos. What do you look for in young designers?

Calvi Brambilla: “We are interested in designers who do their own research.

People who are happy to grow by little steps and who can teach us things, even if that is just a slightly different angle to something we know.

We look for coherence, transparency, sincerity and seriousness.

We do not appreciate those who think they have invented something new (mostly, it’s not the case) but designers who have the humility to know what’s come before them and what’s relevant to move forward”.

An example of a product that you put in production, designed by a young designer?

Calvi Brambilla: “The lamp To-Tie by Guglielmo Poletti. His personal research is focused on materials and on bringing their mechanical possibilities – such as tension or stress – to the limit.

And his lamp is built exactly on this: it’s a glass cylinder with a cable holding the light source that is kept in tension. It’s honest, transparent, coherent and sincere”.

How much does a design company need to be marketing-driven in order to be economically sustainable?

Calvi Brambilla: “A creative company cannot be marketing driven.

We get great insights from marketing about what works but their input is always related to what exists and cannot be visionary due to the very nature of the profession, which is based on data.

So marketing inputs are key but need to be associated with that of the R&D engineers and of the freelance designers whom we work with.

All these inputs are partial and our role, as design curators, is like that of a film director: we need to put all this together and ensure that what comes out is interesting”.