Designing in a time of scarcity: a lesson from the 1930s

If you are passionate about design you probably know a lot about Franco Albini who authored some of the most iconic furniture pieces as well as architectures and urban projects (should this not be the case, there is a useful biography here).

While Albini’s life achievements are well known, his design approach isn’t, mainly because he never codified it despite working rigorously with it.

His son Marco recently did though.

After working for years with his father, he came up with the 5 points recipe which is the focus of our story: because the way Franco Albini designed almost a century ago gives food for thought to us today, living in a time of scarcity yet still mentally bound to a time of abundance.

We have reached Paola Albini, Franco’s grand-daughter and president of the Foundation that is entitled to him, to discuss.

Franco Albini’s design approach consisted of 5 points:

- Take things apart

- Look for their essence

- Re-compose them

- Verify the outcome

- Act throughout with a sense of social responsibility

Which bring us very close to the 4Rs of the Circular Economy: Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Recycle.

1. Take things apart

Albini would famously open up objects in his home and dismantle them to discover how they were made and think of how they could be made better. It would drive his wife a little crazy, apparently.

“When you have a problem, you will find out that it’s easier to solve it if you can break it up in small chunks and then face them one at the time”.

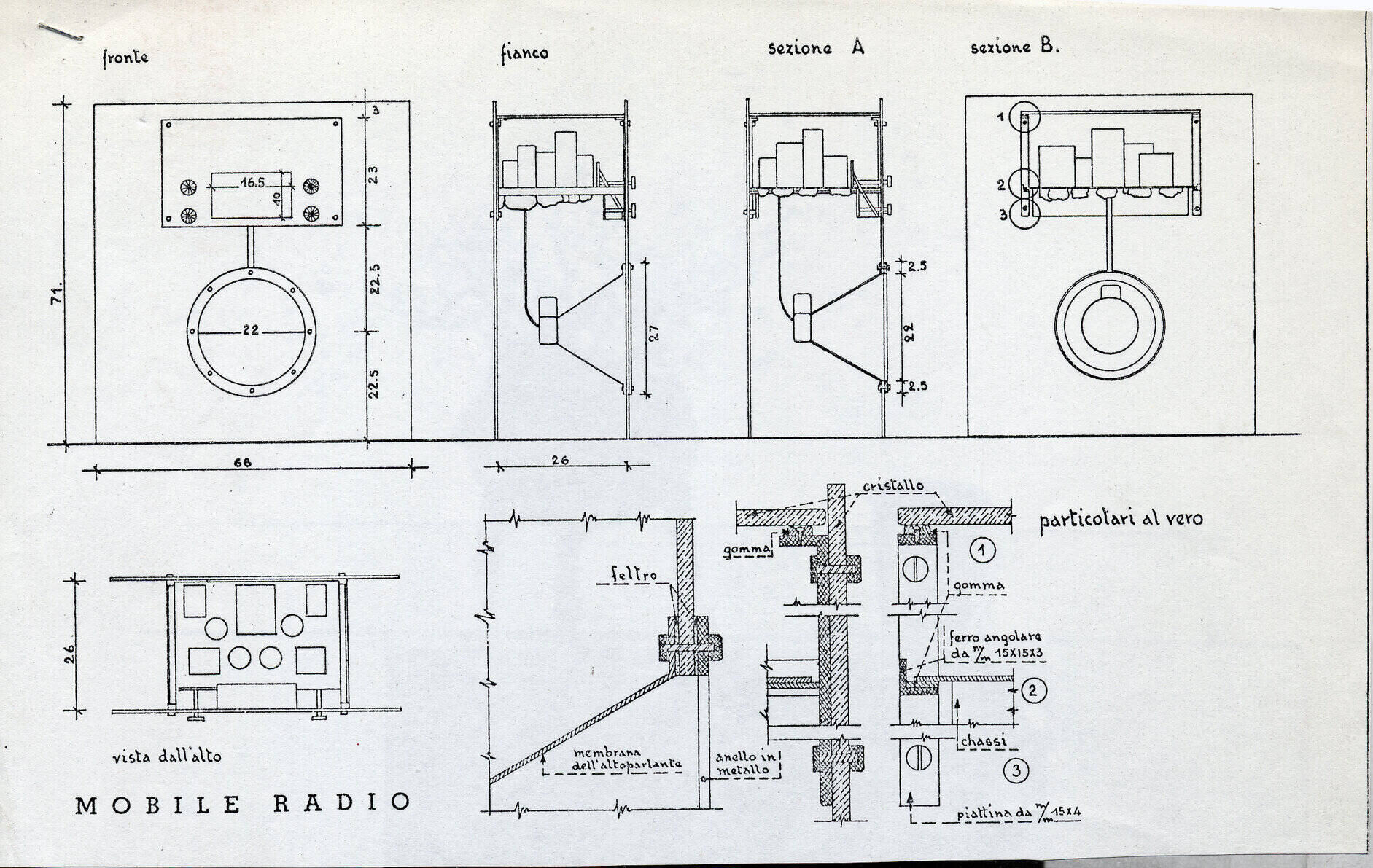

He did so, in 1938, with a radio.

At that time, radios were embedded in a box and placed in pieces of wooden furniture.

Albini opened the mantlepiece, took the box away and basically stripped the radio down to its components.

It is during dismantling that you get to know an object intimately: what each component is for, how (and if) it contributes to the overall function.

Taking things apart to learn from them requires a particular mental approach: “your purpose should be to expose what’s hidden, to turn what’s invisible in something obvious”, explains Paola Albini.

“Your focus is on understanding who does what, and why something is where it is. It’s a discovery journey or a dialogue between you and the object. You will often realize that a lot of stuff is, indeed, redundant. An issue that a better design can solve.”

2. Looking for the essence

As most designers of his time, Franco Albini was convinced that function was the primary objective of design: he wanted to make things work.

They had to do so using a little material as possible, though, and making the smallest effort (today we would say: using as little energy as can be). While providing the lightest and most aethereal visual experience that could be achieved.

“The attitude towards dismantling that I explained earlier is key to search for the essence of objects”, continues Paola.

But how do you find this essence?

“You start from the purpose of the object: why does it need to exist? What is its function?” says Paola Albini.

The essence is what makes the object be what it is: if you take it out, it would cease to exist or to work as such.

Finding the core of an object may be easy in theory. Yet in practice it requires technical skills that are of utmost importance for industrial designers.

In the case of the radio, for instance, the heart of the object are clearly the technological components. But you cannot decide which ones to keep unless you have some knowledge of electronics (or your partner with someone who does).

While if we were talking about a bookshelf – another object that Albini worked on, for instance with the Veliero, as we will see later – some knowledge of mechanics and statics would be required.

3. Re-compose them

This is the most “creative” part of the process. But also the one in which the designer has to be super careful not to be carried away.

“What I admire the most in my grand-father’s work is his strict refusal, throughout his life, to follow fashions and trends”, recalls Paola.

“He lived throughout the 20th century and styles came and went slower than they do today but were perhaps more pervasive in people’s minds. First of all because they lasted longer. Secondly because they often stemmed from actual philosophical or political thinking”.

“Despite this, Albini stuck to his original idea of reduction to the essence and re-composition. And never added anything to his projects that was not strictly required for function”.

When you re-compose an object starting from its essence, you will necessarily have to add something.

Albini would add materials only on the loading points and brought the elements that made the core of the object to the front,

to show off their role as supporters of the main function.

With the radio, he placed components on two crystal sheets and made them visible, delivering a design that look astonishingly contemporary today and probably out of this world back then.

“If you were engulfed in styling, you would end up adding something more than just the essential, thinking it would give more character to your object”, says Paola. “Yet

items turn timeless only when they are totally oblivious of fashionable aesthetics,

those, for instance, that help curators place them in a certain moment in time”.

Actually the Albini radio is very difficult to date: it could easily be a 21st century object…

4. Verify the outcome

Since the function is key, ensuring that everything works is paramount.

In Albini’s case, it sometimes didn’t because he pushed the boundaries of what was possible too far.

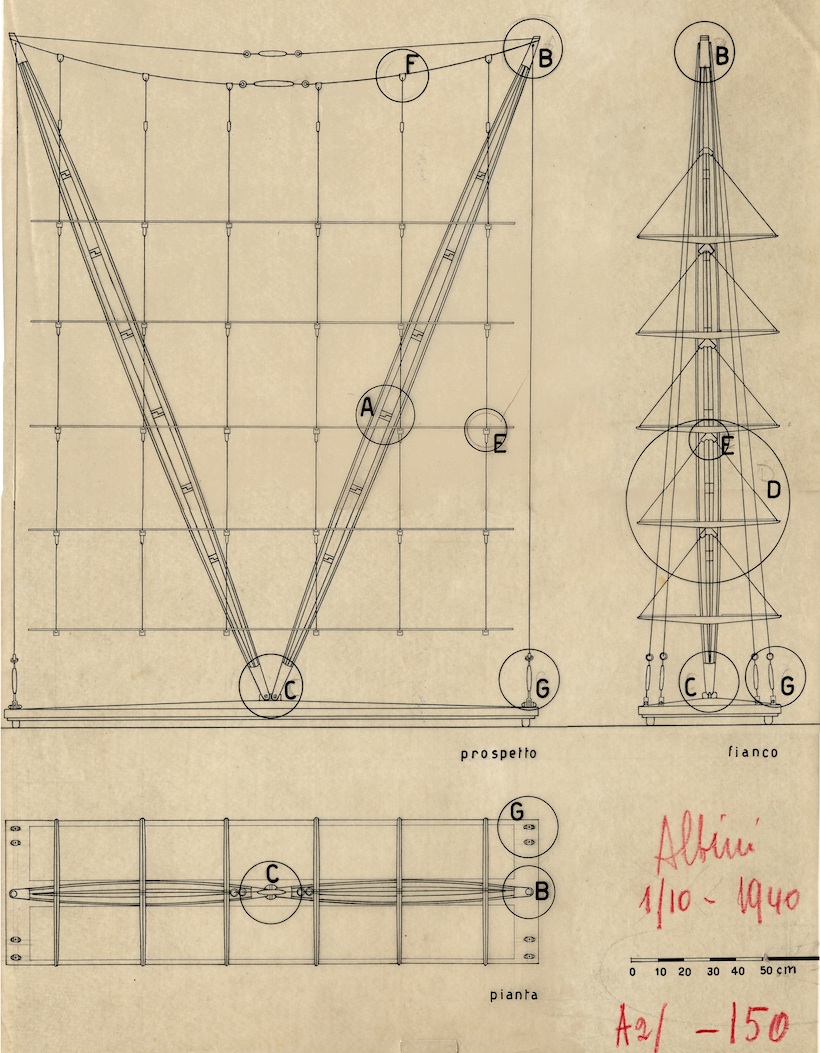

It happened for instance with the Veliero bookshelf.

“The purpose of a bookshelf is to show books. So he deconstructed the piece of furniture, and created an exposed structure: two ash wood rods onto which laminated glass shelves are suspended through a system of 4 mm steel rods”, explains Paola.

It was a total revolution, tapping into the world of civil engineering (think bridges) and nautical design (think of the systems of pulls in a sailing yacht).

“Yet one night the prototype collapsed in his own living room shuttering the glass shelved in thousands of bits and Albini abandoned the design”.

It takes some courage to leave something you worked so hard on but there was no point in carrying of if it didn’t work.

“Nothing was wasted, though, also intellectually”, says Paola.

“His design approach was very much hands on which also means that errors are part of the learning curve. Many other projects by Albini, indeed, kept some of the thinking that he originated through the dismantling and re-constructing of bookshelves which resulted in Veliero”.

Which, by the way, turned into an actual product in 2011, when, also thanks to new technologies, Albini’s son and Cassina engineers were able to make the original pulling system it work.

5. Act throughout with a sense of social responsibility

When Albini lived, there were no climate issue or raw material shortages. When he talked about social responsibility, he meant to underline the role of the designer in creating relevant objects (or spaces, building and urban projects, as he did).

“There was no space for redundant, useless stuff in his agenda”, says Paola. “Each one of his creations had to serve a function and have a social impact: support the creation of new habits, moving towards modernity.

What does it all mean for today’s designers?

Following the 5 ingredients of the Albini recipe today can be extremely useful:

- It helps us getting down to basics and build from there, focusing on necessity

- It brings us to use a minimal amount of materials while achieving functional results

- It teaches us the importance of knowledge in terms of materials and mechanics: skills that are often passed on as engineering-related while they are key also for designers

- It leads to design-for-disassembly which facilitates recycling at the end of life

- It fosters collaborations: Albini himself was never working alone on projects but was extremely active within the design community of his time. When trying to solve complex issues, more heads think better than one. Today, when talking about sustainability, multi-disciplinarity is key.

What about aesthetics?

The best part of this story is that while following a very rational method, Albini managed to achieve exceptional results also in terms of aesthetic.

“This is because he aimed at reducing but at doing so in a poetic way”, explains Paola.

“Poetry doesn’t come from abundance but by focusing on what matters and has a meaning. And on being able to bring all this to the outside for all to see”.

This, also, is a very contemporary sentiment, especially after the pandemic and its side-effects on our life styles and appreciation of nature, of closed contacts and of our homes.

Reduction should thus not equal to giving up on beauty but, rather, to finding a better, most lasting and sustainable beauty in all we do as designers.