Uncomfortable insights into plastic and bioplastic

The images illustrating this article are part of an artistic project called Life in Plastic by Scottish artist David Gilliver. More on this after the article

A giant jet crashes near Heathrow; the most disastrous traffic jam in its history occurs in central London; a nuclear submarine disappears in the Atlantic. These three apparently unrelated incidents are connected by a mysterious thread, soon revealed in all its terrifying gravity: plastic fails to do its job, eaten away by a bacterium.

Doctor Who enthusiasts will probably recognize the plot of Mutant 59 The Plastic Eater a sci-fi classic published in 1972 by Gerry Davis e Kit Pedler (the latter one being the unofficial scientific advisor for iconic TV series during the late William Hartnell and early Patrick Troughton eras).

The story of Mutant 59 is Marinella Levi’s fav to quote to plastic haters, a cohort that – as the Materials Science and Technology professor and Director of the Department of Chemistry, Materials and Chemical Engineering “Giulio Natta” at the Politecnico di Milano says – “is larger than ever, sadly blinding the public at large in front of the real issue when it comes to plastic and sustainability”.

And the issue is: we should use plastic with respect, dispose of it properly, clean it up where the damage is already done, and design things differently.

Can we live without plastic?

“No, we cannot”, says Professor Levi. “Without plastic and rubber, we would go back a century. We wouldn’t be able to land planes, drive cars, run hospitals, have computers or smartphone (since chips are placed on printed circuit boards). This is a material that also recently – think masks during the Covid outbreak – saved lives”.

Yet plastic is the enemy number one when people talk about sustainability.

According to Levi, this is a global scam. A distraction from the key issue: we are the bad guys, not plastic.

She claims this numbers at hand. “Plastic is highly necessary to do almost everything that’s why it’s everywhere. Yet its production accounts for only 5% of all oil used world-wide. The global crusade against plastic is not due to the fact that it uses a lot of oil, or it pollutes by emitting CO2 during manufacture (transportation + heating and cooling have a far higher impact). It’s related to the fact that plastic is visible, abandoned on beaches, sucked in by oceans, cluttering cities, spoiling landscapes. But who brought it there?”.

Surely some of you will now be turning up their noses. Plastic is a super controversial issue especially in the design world.

“The issue is us and how we use plastic (for instance for mono-use items, also when other options are available) and leave it around. We should reduce the amount of new plastic we make, yes, when possible: as we should do with all materials. We should conceive and design materials and products to really enter circular economy processes that guarantee environmental sustainability.

We should be serious when we select recycled or bioplastic materials: and serious means

choosing, for example, what allows us to consume less energy than we would using virgin materials and with costs acceptable to the market.

And we should start a global campaign to teach people to see plastic as a resource, stop wasting it and chucking it around, learn to recycle it and reuse it properly”.

If you ask most people, though, especially Gen Z, they are convinced that we should get rid of all plastic and replace it with bioplastic options.

“Most people don’t know how bioplastics are manufactured, nor understand that their mechanical qualities are not always comparable to those of traditional plastic.

Furthermore, the suffix bio is very alluring and confusing, especially when coupled with adjectives such as degradable, biodegradable and compostable.

It makes people think that they are more natural than plastic and that they dissolve”, explains Levi.

So let’s clarify it all.

Are bioplastics natural?

Marinella Levi:

“They are just as normal plastic is. Both are created using natural resources (biomasses and microorganisms or fossils, hence mineral waste) but both require an equally complex chemical process (hence energy) to come to life.

Do bioplastics dissolve?

Marinella Levi:

“It depends on many factors and on which bioplastic we are talking about. So first we need to explain the meaning of the adjectives biodegradable, compostable and degradable, that are different characteristics of materials.

- The word BIODEGRADABLE refers to the ability of a material or substance to be decomposed and broken down into natural substances by living organisms, such as bacteria, fungi and microorganisms, in environments such as soil, water or air. Biodegradation can occur through natural chemical and biological processes, with the use of enzymes and microorganisms.

- COMPOSTABLE means that a material can be decomposed in a controlled environment, such as a composter, where thanks to the action of microorganisms, such as bacteria or fungi, it is transformed into humus, a substance rich in nutrients, which can be used to fertilize the soil and plants.

In general, compostable materials are also biodegradable, but not all biodegradable materials are compostable. For example, a biodegradable material can be decomposed in water or air but is not necessarily capable of being transformed into humus which can subsequently be used as a fertilizer.

- DEGRADABLE: this word is often wrongly used as a synonym of biodegradable. It is therefore important to note that the following materials are NOT biodegradable:

- Plastics: Most plastics are very resistant to degradation, and can persist for many years in the environment.

- Glass: Although glass can be broken into small pieces, it does not decompose naturally.

- Metals: Metals are not degradable by living organisms and can persist for many years in the environment.

- Cans: Metal cans, such as beer and soda cans, are sturdy and do not decompose naturally.

- Ceramics: Ceramics are very resistant to degradation, and can persist for many years in the environment.

These types of materials can cause environmental problems if not handled properly and can be considered persistent waste.

However, these materials can, indeed, must be recycled, undergoing processes that transform them into secondary materials that can still be used over and over again.

When it comes to the biodegradability or compostability of bioplastic, it’s useful to refer to the definitions of the European Environmental Agency,

- Biodegradable plastics are designed to biodegrade in a specific medium (water, soil, compost) under certain conditions and in varying periods of time.

- Industrially compostable plastics are designed to biodegrade in the conditions of an industrial composting plant or an industrial anaerobic digestion plant with a subsequent composting step.

- Home compostable plastics are designed to biodegrade in the conditions of a well-managed home composter at lower temperatures than in industrial composting plants. Most of them also biodegrade in industrial composting plants.

So coming back to your question, does bioplastic dissolve?, the answer is: only compostable bioplastic does, and only in certain conditions. The human factor, how we get rid of plastic (also bioplastic) is key avoiding pollution.

How do you make bioplastic?

Marinella Levi:

“Bioplastics are first and foremost plastics, but in this case they are obtained from renewable biomass or microorganisms instead of fossil raw materials (such as oil).

The process to make bioplastic is as follows:

- If you use renewable resources such as corn starch, sugarcane, or cassava you can get PLA (polylactic acid). The production process for PLA typically starts with the raw materials being fermented and then converted into lactic acid. The lactic acid is then polymerized to form a long chain of molecules, creating a polymer known as PLA, which you then need to process in the same way as you do with the oil-based one

- If you use microorganisms you can get PHA (polyhydroxyalkanoates). They are produced by microorganisms through a process called fermentation. During fermentation, microorganisms such as bacteria metabolize sugars or lipids, converting them into PHA through a series of enzymatic reactions.

What are the pros and cons of using bioplastic?

Marinella Levi:

“Bioplastics are appreciated because they reduce the amount of oil used, the can have a smaller carbon footprint and decompose faster. On paper, it all looks really good.

But saying what is sustainable requires a high intellectual honesty and a great environmental culture in the people who make decisions: the use of shared indicators that are often very complex.

A very rigorous methodology to obtain some of these shared indicators is the Life Cycle Assessment, an engineering and data-based process that measures the environmental impact of the whole life cycle of a product (or even a business) against different impact categories such as: climate change, ozone depletion, eutrophication, acidification, human toxicity (cancer and non-cancer related) respiratory inorganics, ionizing radiation, ecotoxicity, photochemical ozone formation, land use, and resource depletion.

Research has shown that the use of fertilizers and pesticides in crop production and the chemical processes required to turn them into plastic generated a greater number of pollutants and damaged the ozone layer more than traditional plastic, while also requiring extensive land use (land that could be used for producing food for people).

Another big issue has – again – nothing to do with the material but with us being unable to recycle properly.

Even if bioplastics typically made from starch, cellulose, and lactic acid are biodegradable, the way the biodegrade, as we said earlier, depends on their specific composition and production process.

Besides that, in order to break down properly (hence leaving no toxic waste), they require, for example, composting facilities and most cities in the world are not equipped with one.

So waste management is the biggest issue with bioplastic as it is with traditional plastic. In some ways, it could be worse.

If bioplastic ends in the landfill (it may happen) and it is not kept in the right environment to biodegrade (i.e. 50°C+ and humidity) when deprived of oxygen, it degrades under other trash and releases methane. This is 23 times worse as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

If bioplastic is discarded with normal plastic, its not fossil nature contaminates the rest of the plastic which cannot undergo the normal recycling process. The result is that the yield of the recycling process can be greatly worsened.

When is it useful to use bioplastic?

Marinella Levi:

“Bioplastic should replace traditional plastic in single-use items. In some types of packaging, for instance. For shopping when (hopefully rarely) we do not have our own reusable bag), for party glasses, plates, cutlery. But consumers should be properly informed about how to recycle them: they have to be recycled in wet waste to avoid a sort of cross contamination between plastics and bioplastics.

What we should keep in mind is that

there is no black or white solution: a variety of different options, when it comes to plastic, will have to coexist to tackle the environmental issue.

When is it not useful to use bioplastic?

Marinella Levi:

“When we consider the types of bioplastic we have at present, there is no point in using them for long lasting items. In those cases, it’s much better to opt for traditional plastic or, even better, recycled plastic which, at the end of its life span, can be easily recycled again and again.

One has to bear in mind that recycled plastic can have worse properties compared to virgin plastic, and cannot be recycled ad infinitum, but, for sure, at the end of its life cycle, it can be incinerated and the energy contained therein can be recovered.

In the last few years, a lot of designers (and even companies) have been experimenting with bioplastics and used them to produce items that are supposed to be durable: furniture, sneakers, fashion garments, home decorations… This truly doesn’t make sense. Quite the opposite, it sends the wrong message:

it taps into the idea that we can buy things at no impact and throw them out quickly.

When this is truly not the case. Thankfully, it seems that this trend is slightly slowing now”.

Should designers experiment with bioplastic?

Marinella Levi:

“Yes. Getting to know all materials that are available, and figuring out their qualities, is important to understand when it’s good to use them and when it is just a PR exercise. But a much more positive impact would be achieved if designers focused on something else”.

What can designers do if they want to contribute to the plastic issue?

Marinella Levi:

“Focus on making design circular, applying the Rs of the circular economy. These Rs are not mutually exclusive, they are interconnected and implementing them will create a circular economy where resources are kept in use for as long as possible, and waste is minimized.

The Rs of circular design are:

- Rethink: Encouraging businesses to reconsider the entire lifecycle of a product, from design to end-of-life, and to consider the entire value chain.

- Refuse: Avoiding products or packaging that are not necessary or will not be used.

- Reduce: Reducing the amount of resources used in production, packaging and distribution.

- Reuse: Identifying ways to reuse a product or package, rather than discarding it.

- Repair: Encouraging the repair of products instead of disposing of them.

- Refurbish: Refurbishing products that can no longer be repaired, to extend their useful life.

- Re-manufacture: Breaking down products and remanufacturing them into new products.

- Recycle: Recycling materials at the end of their useful life.

- Rot: Composting biodegradable products to convert them into useful resources.

- Continuous Rethink: Continuously rethink the entire process and make adjustments as necessary to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and maximize the circular economy benefits.

[ Read also An industrial designer’s unexpected view on plastics ]

There is a lot designers can do to make the Rs actionable. For instance:

* Design to reduce the amount of materials (not just plastic, obviously), opting for recycled ones whereas durability is not impacted, preferring single materials rather than mixed ones to facilitate recycling

* Apply design for disassembly techniques so that objects can be easily dismantled and repaired (by anyone) and parts eventually recycled

* Educate people to respect plastic and see it as a resource (to properly dispose of) rather than a cheap throw away thing. Designers are great at communicating complex concepts and should be involved by governments and institutions in changing people’s mentality on these issues

* Tackle the microplastics issue. Microplastics comes from a variety of sources:

_ Personal care products: Microbeads, plastic beads found in some toothpastes, body washes, and other personal care products

_ Industrial abrasives, such as those used in blasting, polishing, and cleaning

_ Plastic packaging such as plastic bags, bottles, and packaging (that are broken down by physical processes such as UV light, wave action, or mechanical abrasion, and chemical processes such as photo-degradation).

_ Clothing: Microfibers from synthetic clothing released when washed and entering the water system

_ Vehicle tires: When the tires are worn down, tiny fibers can be released

_ Paints, Marine coatings, Agrochemicals

Lots of work should go into figuring out ways to stop this invisible pollution.

* Promote new food habits: if we buy fruit and vegetables in supermarkets, where logistic chains are long, plastic must be used to lengthen the life of products. Locally grown and sold fresh foods are the way to go and educational campaigns can help

* Experiment with bioplastics: bearing in mind when and how they should be used, as we saw above.

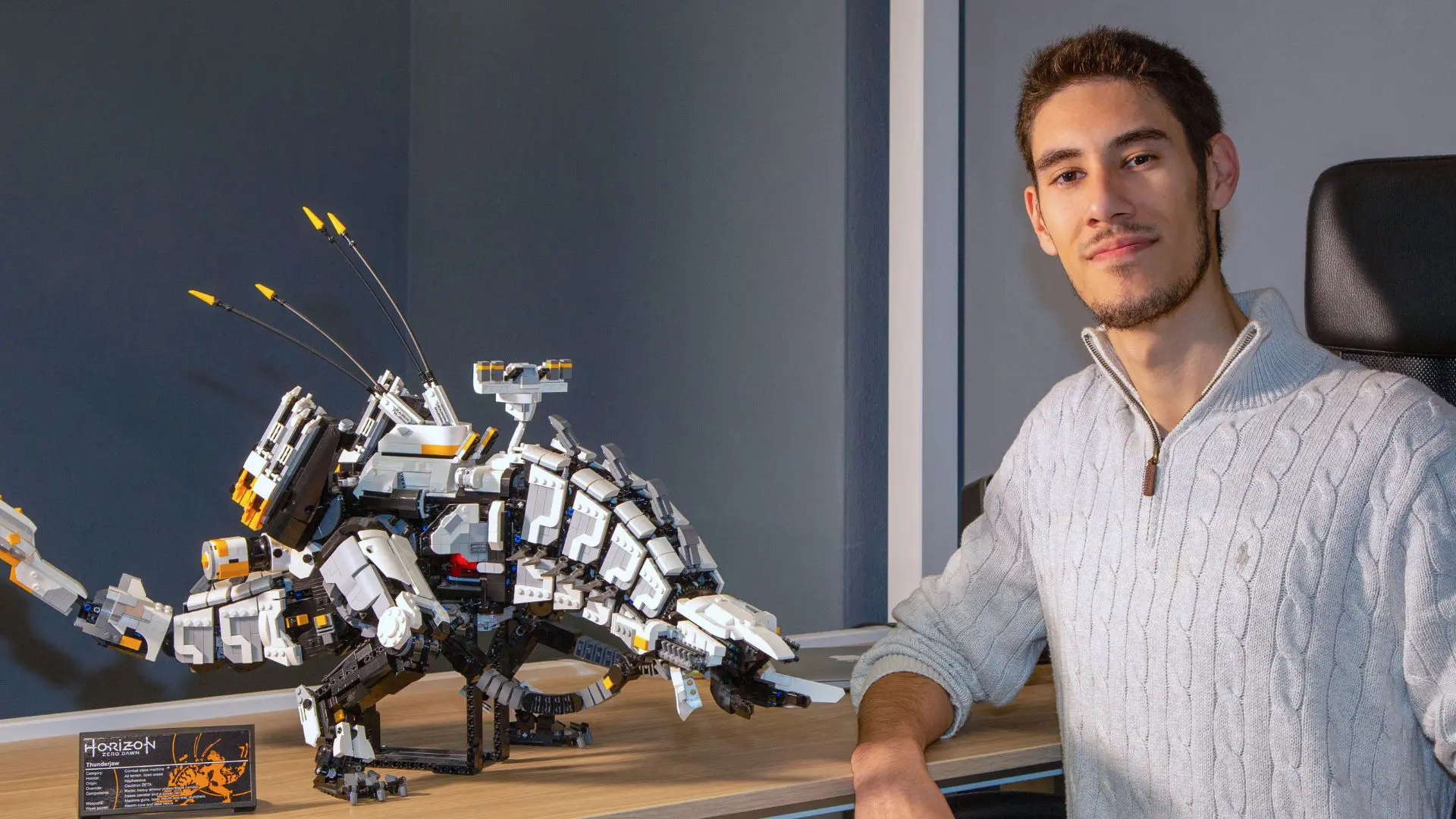

LIFE IN PLASTIC BY DAVID GILLIVER is a project that the Scottish artist started in 2018 to bring to the world’s attention the big issue of plastic littering. In the shots, he placed his signature “little people” in natural settings furnished with discarded plastic found on the beaches and in the lochs of the West Coast of Scotland. We thank David to grant us the use of his beautiful and meaningful images. To know more visit David Gilliver Photography on Facebook or Instagram