Using boundary objects for enhanced design perspectives and insights

What are boundary objects? In the context of Star and Griesemer’s theoretical framework, they are envisioned as inclusive and shared spaces, either physical or virtual, that are activated through interactions.

April heralds springtime in Cambridge, Massachusetts, bringing with it a welcome warmth. During my brief winter break, I had the opportunity to collaborate with Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME) in Budapest, Hungary, and Macromedia University of Applied Sciences in Stuttgart, Germany. These interactions, along with my ongoing design research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, spurred some reflections and early ideas. Particularly captivating was my encounter with the concept of boundary objects, a theory first introduced by sociologists Susan Leigh Star and James R. Griesemer in 1989.

Boundary objects:

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

What are boundary objects?

The term “boundary” often links to notions of peripheries, constraints, clustering, and limitations. Similarly, “objects” typically evoke thoughts of tangible items, possessions, and physical entities.

In the context of Star and Griesemer’s theoretical framework, however, boundary objects are envisioned as inclusive and shared spaces, either physical or virtual, that are activated through interactions. These interactions may be enabled by individuals or communities from various backgrounds to react to the object or to the interplay between objects themselves.

Far from being just physical entities, boundary objects serve as catalysts, fostering environments where individuals or groups from diverse spheres can converge. Here, they offer their unique perspectives and engage in collaborative dialogue, without the prerequisite of agreement.

A map is a boundary object

Maps exemplify the concept of boundary objects by catering to varied interpretations and uses. Individuals consult maps with distinct intentions: some seek navigational guidance, others pinpoint specific locales, and still others interpret virtual maps to grasp the nuances of their surroundings, environmental features, or intricacies of local political climates.

Maps also serve as pivotal tools for aggregating diverse perspectives, aiding in the synthesis of collective understanding. They facilitate collaboration, such as trip planning with family or friends. As boundary objects, maps embody multifaceted significance, reflecting the diverse objectives and levels of different needs from their users.

Immersive technology, Michelin-starred restaurant, and longevity planning

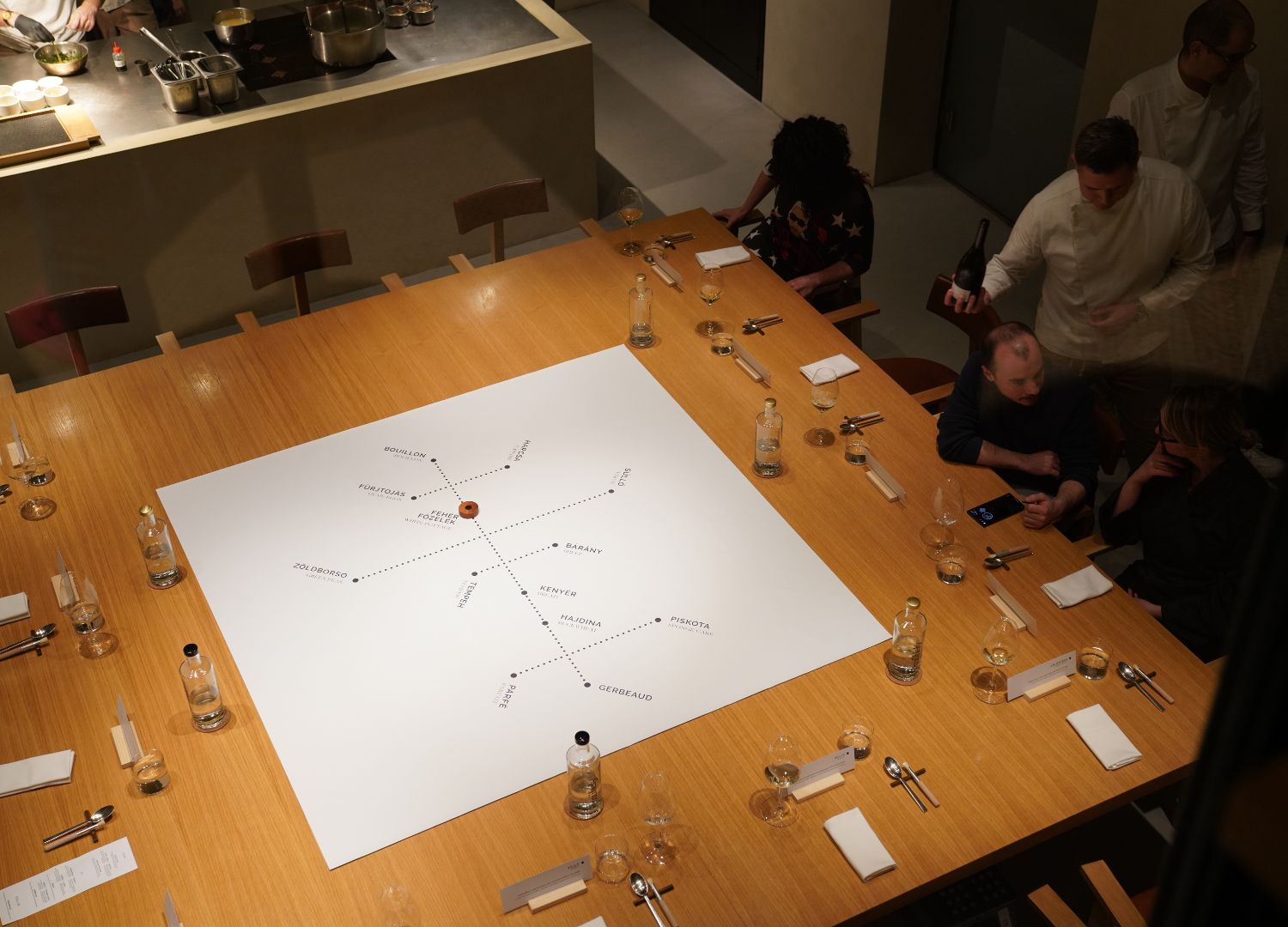

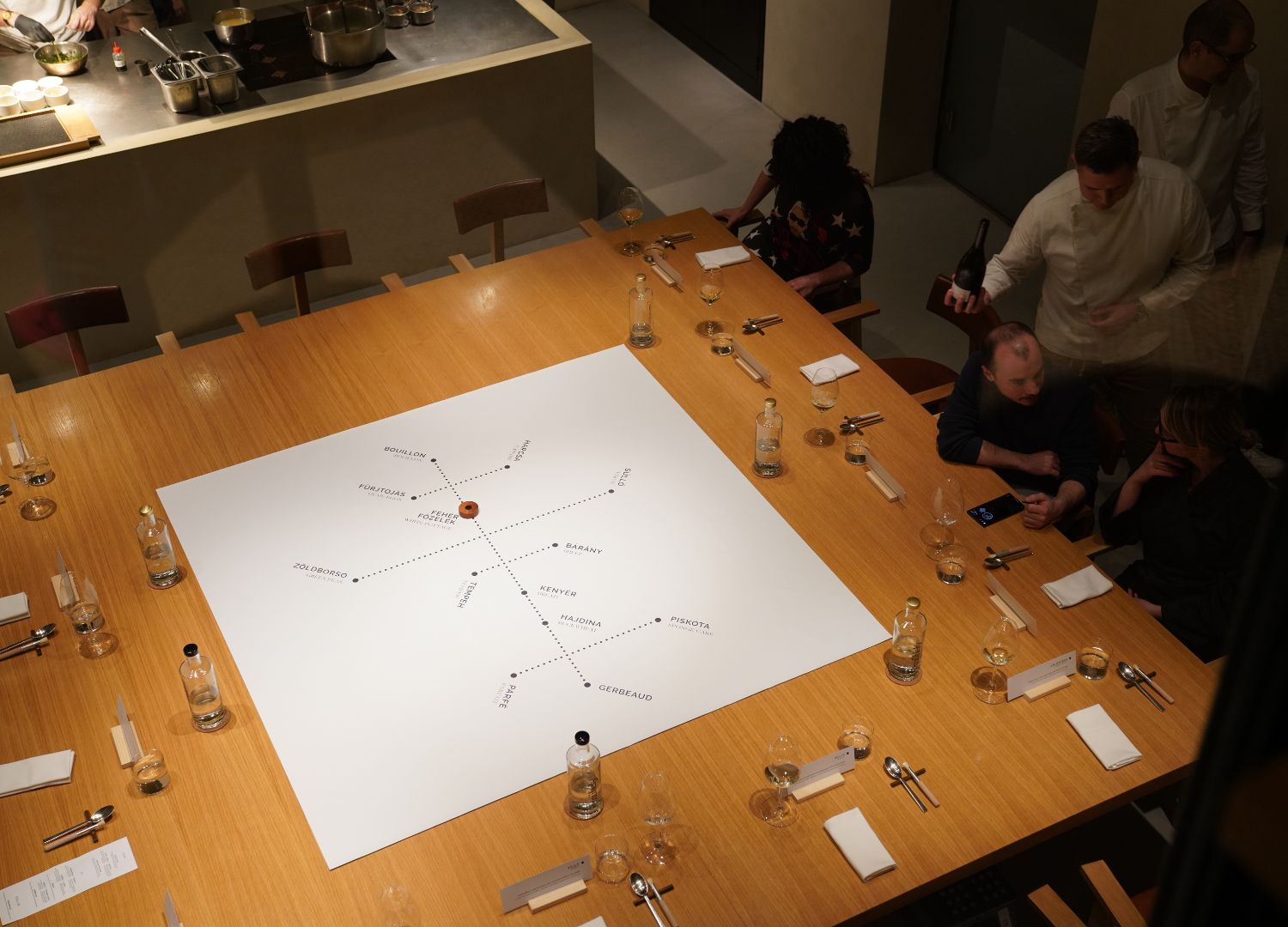

This article examines how boundary objects shape our understanding of daily experiences by exploring three case studies: the Apple Vision Pro retail experience zone, a food-journey-and-gaming map at Onxy restaurant (Figure 1), and the use of 12 tangible artifacts: Longevity Planning Blocks (LPBs).

How might the concept of boundary objects be leveraged to create and curate immersive customer experiences? In what ways can boundary objects enhance our understanding of key stakeholders’ objectives and their decision-making processes?

Furthermore, how can engagement with boundary objects facilitate the learning of new knowledge, such as longevity planning, through interactive and meaningful play (Figure 2)?

Boundary object key takeaways

- Boundary objects help diverse team cooperation without consensus.

- Boundary objects create a shared inclusive space to invite different voices.

- Boundary objects aren’t just objects. They act as a medium to create a condition to welcome individuals or communities from various backgrounds to provide suggestions and to enable collective sense-making.

Case 1—Vision Pro in-store experience zone at Apple store

I scheduled a 30-minute in-store session to experience the latest Vision Pro at the Apple Store in Cambridge. In this context, I pondered: What are the boundary objects? The responses may vary. I consider the boundary object is a Vision Pro in-store experience zone in the physical Apple store (Figure 3).

Upon my arrival, an Apple staff member guided me to this zone, fostering an environment conducive to open dialogue between staff and customers like myself. In that specific Vision Pro Experience Zone, the staff helped me navigate the XR experience through the standardized yet flexible instruction familiarize me with the new coordinate system with new interface and gesture control.

The staff scanned a QR code and reviewed my reservation details to ensure the provision of the correct prescription lenses before I tried on the Vision Pro. This experiential zone encompasses various service design touchpoints, including the Vision Pro itself, a comfortable seating area with sofas, a tablet for guidance, clear instructions, and the guidance of the staff.

Within this zone, the staff adeptly guided me through the XR experience to acquaint me with a novel coordinate system, complete with an innovative interface and gesture controls. In conversing with the staff, it became clear that they, too, are in a process of co-learning alongside the users. This is largely because the Vision Pro is a relatively new product for them as well.

The dedicated experience zone, serving as a boundary object, has the potential to enable and facilitate ongoing learning for both service recipients (users) and providers (Apple staff) over time.

Case 2—A food-journey-and-gaming map at Onyx restaurant

Onyx is a distinguished Michelin-starred restaurant nestled in the heart of Budapest, Hungary. The establishment is renowned for delivering an exquisite customer experience that encompasses the food, ambiance, branding, service, and customer engagement.

Ingeniously designed, the restaurant weaves a thematic narrative through the dimension of time—past, present, and future—across three separate dining spaces. Guests are led through a series of unique dining spaces, each offering an experience themed around a specific era of time.

In the space focused on the past, both the presentation of the dishes and manner of savoring them, or even the music, and the way that guests are served different significantly to evoke a unique memorable experience. The Onyx website advises guests to allot at least three hours for this immersive social dining experience.

A remarkable aspect of the experience at Onyx is the provision of an expansive map detailing six to seven steps, laying out the culinary experience in a sequential manner (Figure 4). For each dish, the chef presents the stories behind it, guiding diners on what to consider and savor throughout their meal.

To my delight, I found myself seated next to Angéla Góg DLA, an art director and food designer for Onyx, and senior lecturer and supervisor at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME), leading the MA program.

During the meal, she and the chef participated in the full dining experience as if they were normal customers, enjoying the food, storytelling, dessert, and wine tasting, to fully experience the customer journey.

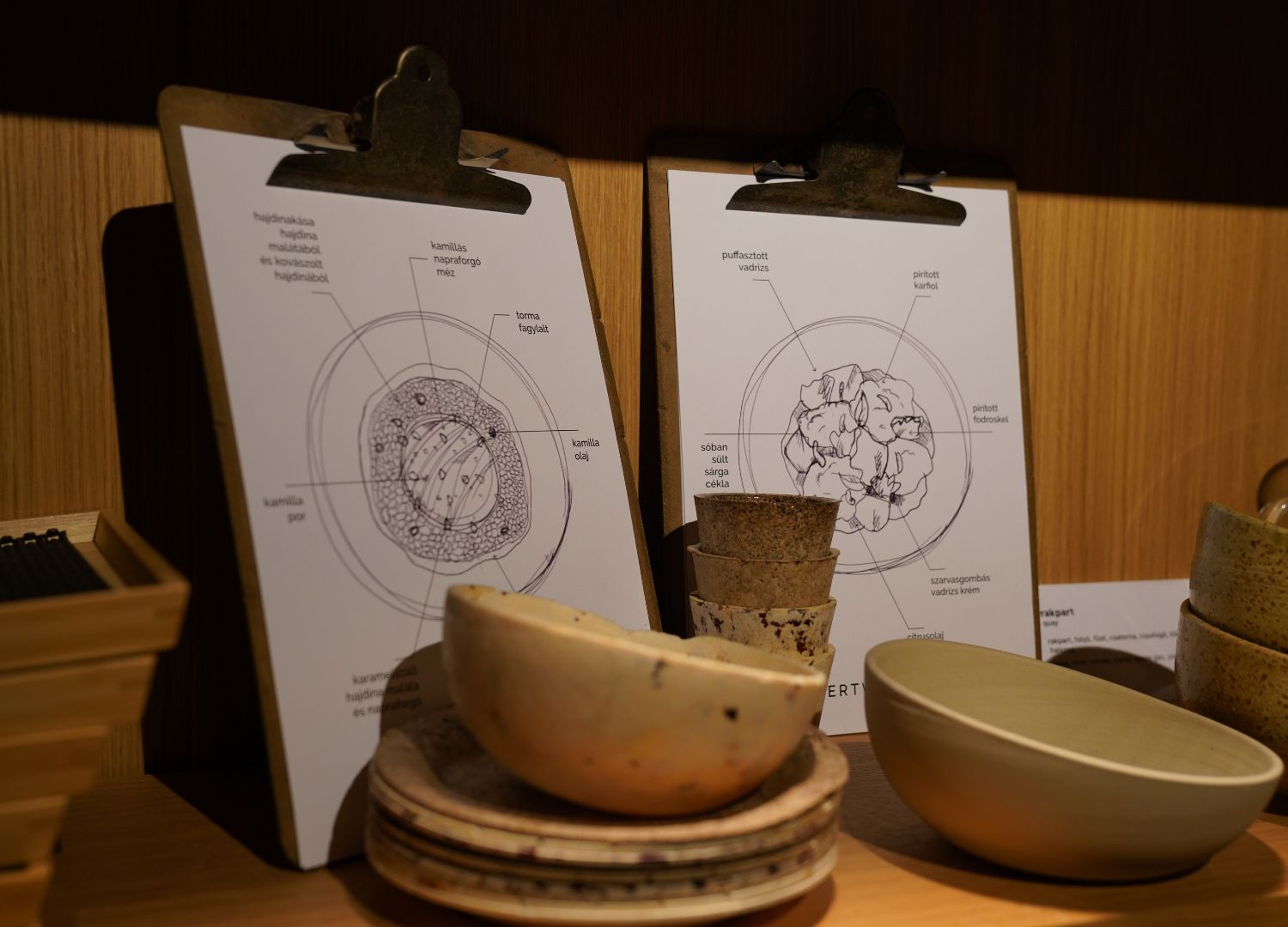

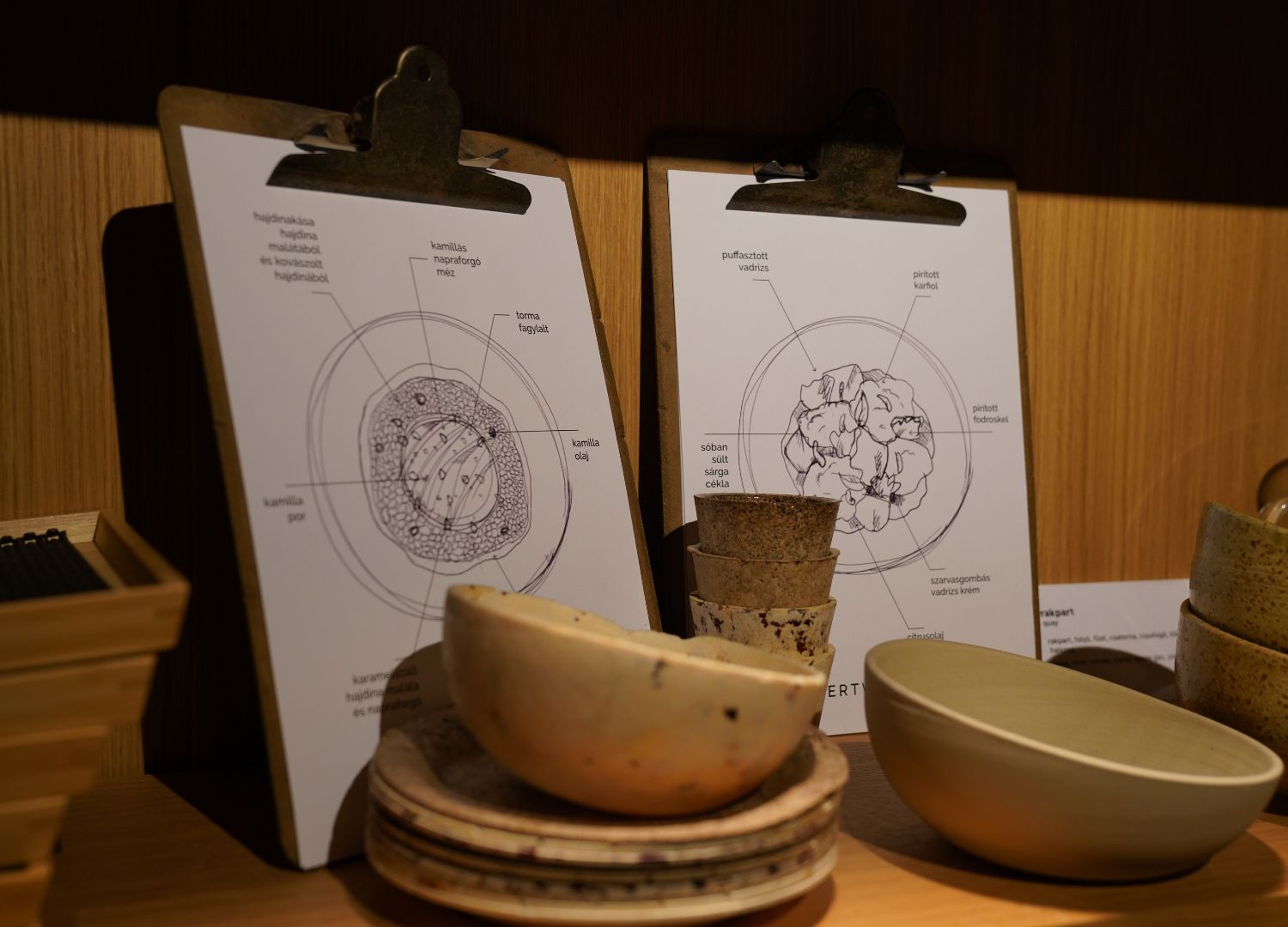

Following the three-hour dining experience, she shared with us an insightful overview of the restaurant’s design philosophy. She elaborated on how she integrated the creative output of her students into the restaurant’s utensil design, such as the imbalanced bowl and playful plate. Angéla explained using her creative process to develop new dishes from initial idea and sketches through experimentation with raw materials to the final presentation (Figure 5).

I was impressed by her comprehensive supervision of the dining experience as a form of social engagement that facilitates celebration and interaction among guests and service providers like chefs and waiters.

Observing the environment, I identified the grand “gaming map” sprawled across the rectangular table as the boundary object. The 12 diners encircle this big map. This map provided guests with a visual cue of the dining sequence and the names of each course (Figures 1, 4, and 7).

The process didn’t require guests to concur with the chef’s ideas; rather, it nurtured an atmosphere conducive to personalized experiences. Guests were encouraged to exchange opinions on the dishes, beverages, and desserts, either with their companions or with other diners, further enriching the communal aspect of the meal.

Case 3— Tangible artifacts: Longevity Planning Blocks (LPBs)

In the realm of financial planning, we have innovatively introduced Longevity Planning Blocks (LPBs), a suite of 12 tactile elements, complete with guided instructions designed to prototype a new approach to longevity planning services (Figure 6).

Developed from the foundational principles of Coughlin’s 8,000-day framework, this pioneering methodology structured retirement into four distinct stages: managing ambiguity, making big decisions, managing complexity, and living solo.

The LPBs aim to facilitate individuals or communities from different backgrounds in expressing their thoughts, ideas, and concerns in a constructive manner through engaging, thoughtful serious play.

Each LPB features a question pertinent to life experiences, accompanied by a relevant photograph and symbol. Examples include contemplations like “How do you obtain an ice cream cone?”, “Who will provide care for you?”, and “How do you change a light bulb at home?” These questions are instrumental in sparking dialogue and reflection on sensitive and challenging topics.

As boundary objects, LPBs are indispensable for initiating and guiding conversations on delicate and often complex subjects such as financial planning, investment strategies, education, family, community, risk management, and other personal factors linked to one’s longevity planning.

Financial advisors or longevity coaches can employ LPBs to gain insight into the evolving necessities faced by individuals of diverse backgrounds, thereby facilitating understanding without the need for agreement.

Summary

In this transformative age, marked by advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and mixed reality (XR), humanity grapples with unprecedentedly complex and systemic problems, such as climate change, aging, sustainability, and design for social impact. Thus, the concept of boundary objects has become very valuable to solve these difficult social-technological challenges.

Learning 1—Make collective sense-making from diverse communities

The concept of boundary objects is instrumental in facilitating collective sense-making among individuals or communities with diverse backgrounds. They support cooperation by providing a shared space that encourages contributions from different voices, even in the absence of consensus. Boundary objects act as tools for collaboration, fostering understanding and cooperation without necessarily achieving agreement.

Boundary objects become invaluable in this context of change; they gather, facilitate, and celebrate innovative thinking and creative initiatives. They serve as a bridge linking people, intentions, products, procedures, and platforms across a spectrum of communities and backgrounds, fostering a collective, creative synthesis.

Learning 2—Trigger creative tensions

The three case studies have enabled me to think of the value of boundary objects. The benefit lies in their capacity to inspire us as designers to navigate and harness the creative tension among objects, services, and experiences within complex and varied social contexts.

It motivates us to shape our thinking process comprehensively, considering the interplay between the foreground and background, the service providers and the recipients, as well as the overarching strategy and immediate actions, and not least, the relationship between people and their purpose.

Learning 3—Consider political, cultural, and social dimensions

When we consider everyday objects, such as our interactions with individuals, or various behaviors, as boundary objects, it encourages us to contemplate the political, cultural, and social dimensions that these objects may embody.

Reference link: