A self-reflection on research ethics and design process

ChatGPT, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), 4D printing, and Metaverse are not just buzzwords anymore in this era of digital and organizational transformation, but have also impacted our research methodologies, thinking processes, and theoretical frameworks.

With these external changes in emerging technologies and socioeconomic shifts, finding adaptable and scalable solutions has become increasingly important. And how we find suitable solutions in an ethical, inclusive, and respectful way is also critical, since we need to put more effort into taking essential desires, needs, and core topics around people and with people into account.

Therefore, the purpose of the article is to discuss the intersection between research ethics and the design process in facing these complicated and systemic social-technological problems and how we can ethically identify people’s new needs, adapt our behavior, modify the study process, and prepare and envision the foreseeable future.

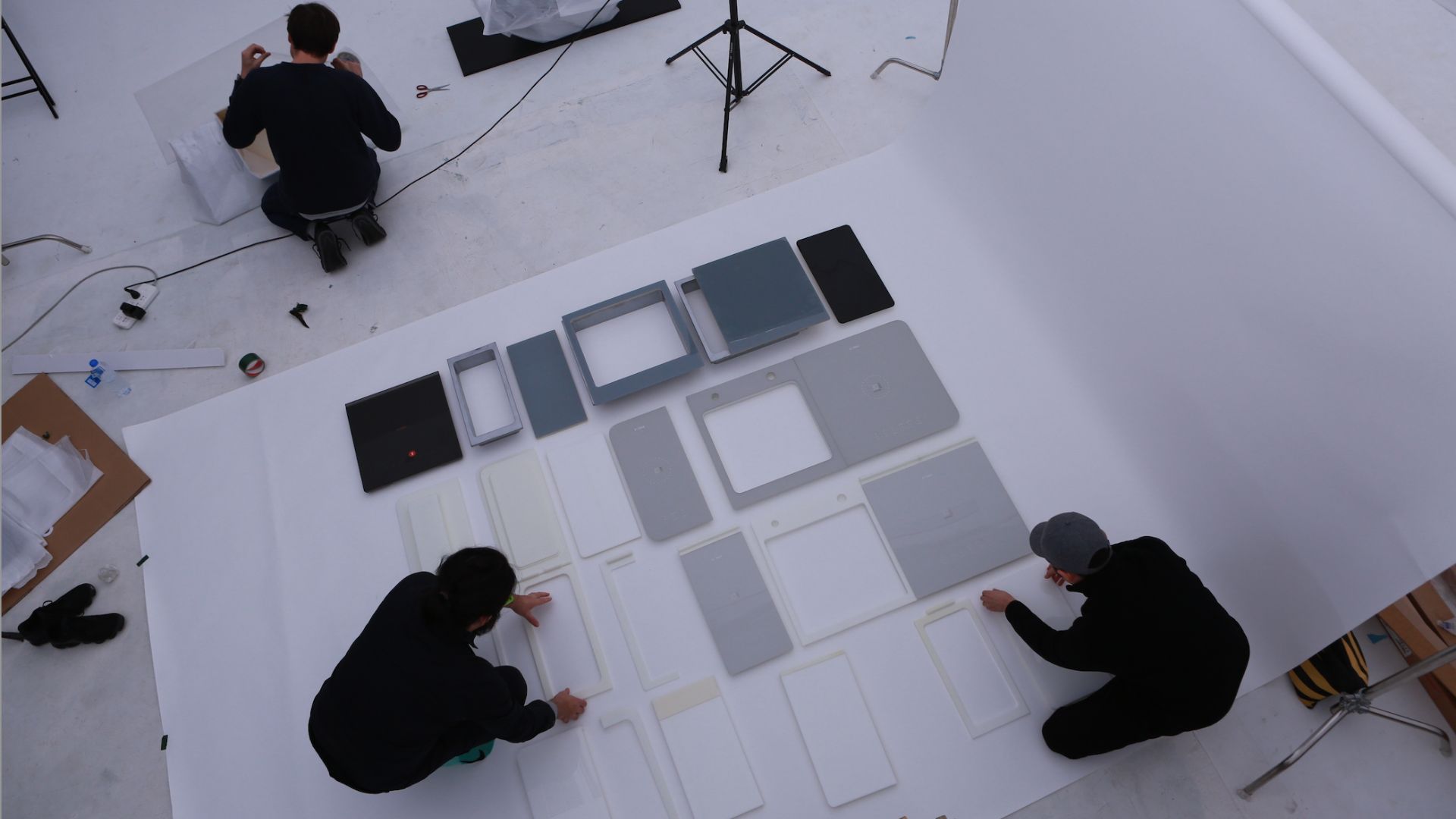

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

While discussing the principles and high-level observations, I will share some of my Ph.D. research projects and master thesis collaborating with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) AgeLab [1], my previous case studies working with two design consultancies, IDEO [2] and Continuum [3], as well as my side projects.

The primary goal of the article is to reflect on my learnings in the research phase through the lens of research ethics and the design process. I will also explore how I as a designer deal with privacy-related topics and how designers integrate an ethic of care into design projects, as well as the cost and value on the individual, institutional, and societal levels.

The principle of care and design research ethics

In the process of design research, we as design researchers don’t have the same amount of transparent information about every one of the research participants. Usually, we might know more details than those being interviewed in advance before the user interview or experiments, leading to a different power dynamic between the interviewer and interviewee. It also opens new opportunities to think about our research ethics and how we can improve them.

In Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method [4], the authors proposed eight principles of care:

- Informed consent

- Mitigation of institutional risk

- Anonymity

- Deception

- Sex and intimacy

- Compensation

- Taking leave

- Accurate portrayal

In the Little Book of Design Research Ethics [5], Jane Fulton Suri, IDEO Partner Emerita mentioned three timeless principles that guide most of our work: 1) respect, 2) honesty, and 3) responsibility to discuss how to integrate human-centered design and design process with ethics.

While conducting experiments in the field, I want to explore the three most common and useful principles of care among all these bullet points and materials: 1) informed consent, 2) anonymity, and 3) compensation. These echo my personal design journey in my profession.

INFORMED CONSENT: reach an agreement and make the process transparent

We can view informed consent on two levels: institutional and individual. Normally in school, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or Human Subjects Offices are administrative units in charge of research ethics.

When I did the human subject research for my master’s thesis project for the first time, I had to finish my COUHES (Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects [6]) application first by taking a few online courses with quizzes not only to help me understand the research protocol specifically focusing on ethics, but also to think broadly about the purpose of the research, research method, recruitment criteria, deployment strategy, and the place and format to conduct the research.

At school, most of the research I worked on was low-risk and qualified for low-risk review or exemption. To kick off a research project at MIT, I needed consent from not only my research participants, but also from the institute (MIT).

A formal consent form is important to inform your research participants or the school administrative unit that you are conducting the specific research with the permission of both participants and the school. A properly designed consent form includes content, the clarity of information, and the research preparation process, which is critical before conducting any experiments.

A consent form is like a contract to inform participants or the school in advance about the things you want to do, e.g., quoting people’s comments, revealing people’s identities, recording the interview sessions and other documentation details. Essentially, informed consent helps us as researchers or designers to reach a constructive agreement and ensure the research process is transparent and respectful.

ANONYMITY: anonymously contribute personal data to improve systems collectively

Anonymity, as a principle of care, touches on people’s private and sensitive information. I’m also curious about how people perceive the concept of anonymity during the research. When working on my master’s thesis at MIT, I developed smart IoT slippers for an aging population. A major part of it consisted of interviewing expert participants about data privacy. The experts from the interviews came from the field of product design, technology, and education.

Some people didn’t want their smart devices to collect and store data including personal preferences and personal information, or upload them to the cloud; extreme users said that they allowed smart devices to process their information locally without connecting to the internet; still, some had no problem having their data used either anonymously or not.

However, some people’s responses impressed me and enabled me to consider the tension between individual data privacy and collective benefit, e.g., how to make a better and smarter system. They want to contribute their anonymous data to improve the overall smart IoT ecosystem. For the purpose of creating a better system, participants’ data can be analyzed, but it needs to be processed anonymously.

In this example, these experts still wanted to contribute to the research for better and smarter IoT devices. But the trust and values lie in one premise, the power of control: do they have the option to decide whether they want to share their data and how, anonymously or not?

COMPENSATION: indicate respect to appreciate participants’ time and knowledge

In the early stage of research, we tend to recruit potential interviewees or invite survey participants by starting with our personal connections: family, friends, or colleagues. We consider the initial phase a pilot test to refine the discussion/interview guide and overall interview flow and questions.

As our personal connections are relatively more accessible than hiring a professional recruiter to help us in the recruiting process, we take it for granted and normally invite people to join for free or with a small fee. It can easily overlook the bottom line of research ethics, since we shouldn’t utilize our personal connections e.g., friends or family to leverage their time for free for the project.

If we “unpaid” or “underpaid” people for their almost-free labor such as their time and knowledge, it would cause a vicious cycle. There is no such thing as a free lunch. We need to be mindful that our research behavior aligns with our research ethics.

Giving compensation is critical for interviewers and interviewees, since both sides will spend their time, energy, and money on the research. For example, an interviewee needs to pay attention for an hour or even longer to join the session with the interviewer to share their thoughts, valuable working experiences, and creative ideas, whereas interviewers need to prepare provocative questions, decent-length surveys, and interactive activities to engage with the participants to capture the conversation.

Compensation can be considered a sign of mutual respect. It’s a medium to connect researchers and participants that indicates more than just giving money to the interviewee; it also demonstrates professionalism and appreciation as an implicit way to transfer invaluable knowledge and experience from participants.

Before I start to ask our participants or interviewees questions, I feel more solid and safe if I give them incentives or gift cards. When I worked at IDEO and looked for expert interviewees for a kitchen hood product design project, we made sure the recruiter’s fee, expert interviewees’ fee, and potential travel expenses are all covered in the recruitment budget.

SUMMARY: solve complicated challenges with ethical, inclusive, and respectful approaches.

The short reflection was inspired by the MIT graduate course: Qualitative Research Methods (CMS.702/802) by Professor T.L. Taylor. It helped me think as a designer with a passion for design in academia and research to promote the importance of integrating research ethics into the design process.

The article only briefly covers three principles of care by exploring 1) informed consent: how to reach an agreement and make the process transparent, 2) anonymity: why people want to anonymously contribute personal data collectively to improve systems, and 3) compensation: what indicates respect for participants’ time and knowledge.

When we face complicated and systemic challenges, figuring out solutions is only one aspect. We also need to consider how to come up with solutions with ethical, inclusive, and respectful approaches. The principle of care is a great starting point.

Reference

- Coughlin, J. F., 2023, “MIT AgeLab” [Online]. Available here

- IDEO, 2023, “IDEO” [Online]. Available here

- Zaccai, G., 2023, “Continuum” [Online]. Available here

- Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., and Taylor, T. L., eds., 2012, Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method, Princeton University Press, Princeton. Available here

- Suri, J. F., and IDEO, eds., 2015, The Little Book of Design Research Ethics, IDEO, Place of publication not identified. Available here

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2023, “Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects” [Online]. Available here