Building an AgeTech City: Services, Community, and Technology

How to redesign Taipei Mass Rapid Transit through the lens of service design for longevity

Design for aging has become a trend across almost every industry including people’s daily lives, public and private sector services, governmental policies, business strategies, economics, and even our education systems.

Aging is no longer recognized as a problem; instead it’s a natural life cycle process in nature. The real problems lie in how we build enough or better capabilities through our social infrastructures, systems, communities, services, and technologies to improve people’s quality of life.

This summer, invited by Vice President and Professor Tony Kuo from Shih Chien University (SCU), Taiwan, we opened a weeklong experimental design sprint course collaborating with Taipei Metro Station and SCU Smart Service Management program to envision future public transportation design to build an AgeTech city including the design of products, services, experiences, and systems.

How do we redesign Taipei Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) through the lens of service design for longevity? How do we cultivate age-friendly cultures, workforce, and policies? How do we reshape our public transportation services and systems to face the challenges of super-aging societies’ transformation?

Positioned as a general education course with cross-disciplinary participants

We recruited 32 students, and the course was open to international students of both undergraduate and graduate levels from various backgrounds: business, social science, product design, media design, architecture design, service design, and other majors.

This is not a traditional design course; instead, we positioned it as a general education course to experience how to apply a service design approaches to reframe, create, prototype, and test complicated design challenges around aging and longevity.

Inspired by the IDEO design approach, we designed seven worksheets based on the four stages of the design process: inspiration, ideation, identification, and implementation.

The design sprint course is relatively intense in terms of process, especially for students without design backgrounds, since we want to cover fieldwork, design research, prototyping, and testing within a week.

Design solutions and processes should avoid older adults’ labels

Focusing on topics around the design for an aging population doesn’t mean we only view older adults as our targeted audience.

Therefore, we broadened our course project brief and thinking process by re-emphasizing the importance of inclusiveness, diversity, and universal considerations when we come up with design solutions. Especially, nobody in products or services want to be attached to the label of “designing for older people.”

Holmes, the author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design and Chief Design Officer and EVP at Salesforce, discussed the question, “How can inclusive methods build elegant design solutions that work for all?” She shared that inclusive design is like two different cogs finding the best way to match to transfer motion by engaging with projections on another cog.

Most importantly, we want to encourage students to put on the lens of longevity and service design to re-see and observe our world and revisit the experiences we have in our daily lives. We aim not to design for older adults, but to shift the mindset and framework to design for longevity (D4L).

Explore service design through the longevity lens

What do we mean by applying a D4L lens? One simple explanation is to think about design solutions in the context of time and scenarios. Obviously, design solutions (what) will and should be modified and dependent on users (who), time (when), and context (where).

The above features make the design intention (why) much more critical and harder to grasp, since we need to study our target audiences well to understand and address their pain points, let alone come up with solutions.

Conduct fieldwork research at Taipei Metro Operations Control Center.

One highlight of the courses was visiting Taipei Metro Operations Control Center as our field study. Two experts from Taipei Metro Station took students to see what they’ve designed for user-friendly and aging-friendly space and wayfinding at Zhongshan Metro Station.

For example, Zhongshan Metro Station is an experimental metro station to conduct most pilot tests. They have prototyped and integrated new technologies to test new designs frequently.

From the Taipei Metro Station research, they observed that most older adults won’t look up or don’t see the signage hanging on the ceiling. Instead, they look at the floor frequently searching for the public elevators or restrooms.

Therefore, Zhongshan Metro Station not only enlarged the signage and font but also added new wayfinding stickers on the floor with a matte non-reflective surface.

Another example is they had one new voice-control ticketing machine to help people with visually impairments. The machine can also recognize different spoken languages such as Japanese and English.

In general, joining this half-day fieldwork has greatly helped us get a better picture of our design challenges and get inspired by insightful conversations with the experts and guides from Taipei Metro Station. However, students still need to conduct expert interviews, user intercepts, and surveys before moving into the design phase.

Design process is the destination

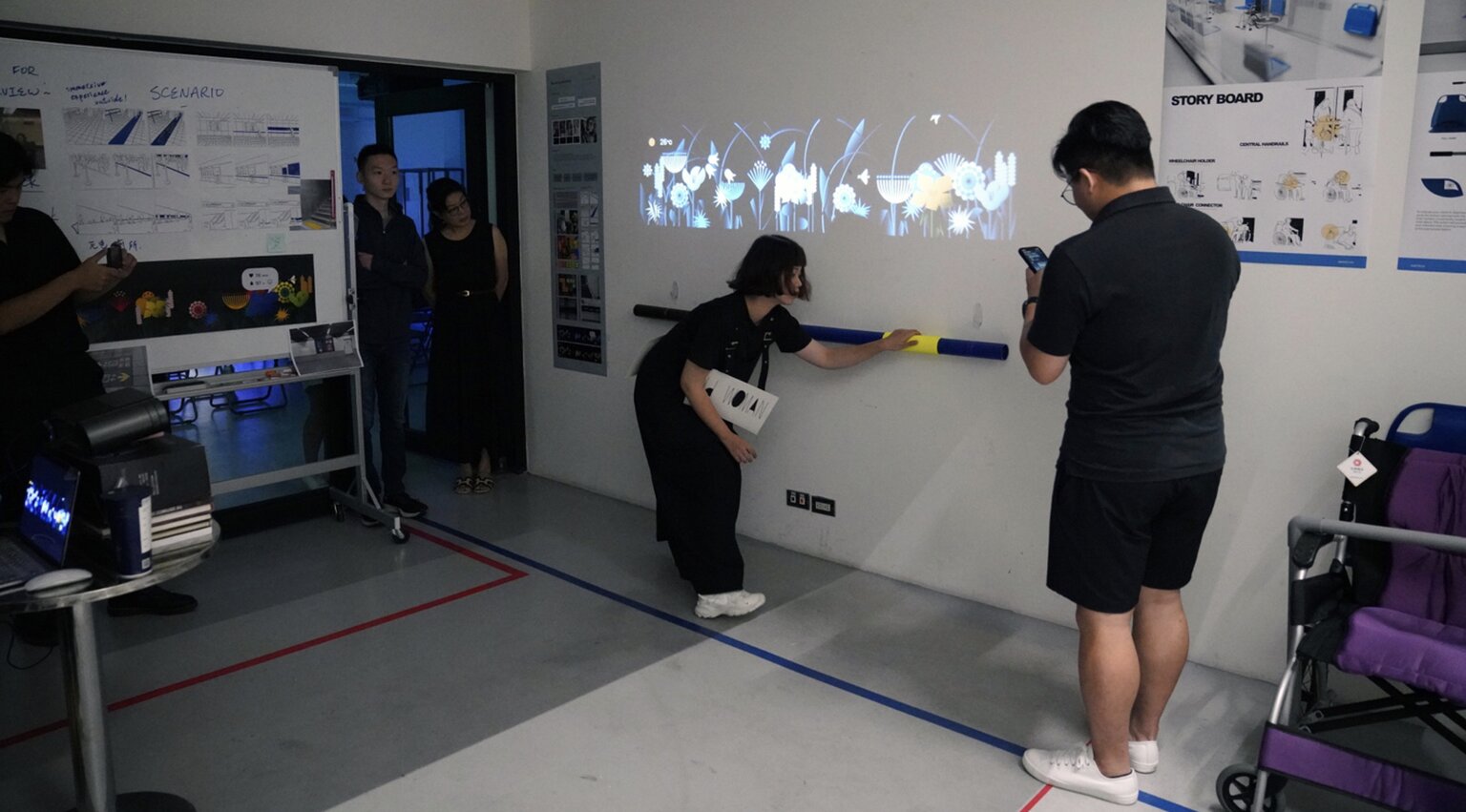

In the course, we had 7 teams with 4 to 5 students each. It’s wonderful to see student team projects demonstrate their hard work and creativity within a week.

One student team focused on train cars seating experience design for an aging population to create a universal design environment. Another team redesigned metro station wayfinding systems combined with public interactive screens and sensors that can provide people’s healthcare information as an engaging approach to make relationships with people and the metro station enjoyable and meaningful.

Another team re-imagined translating the metro station’s public underground indoor space into a welcoming gym or playground for local communities to exercise.

I enjoyed the students’ creativity and energy to give Taipei Metro Station many great ideas and strategies. From the lecturer’s perspective, I care more about the design process and details than the actual design result or design expression.

The course is not positioned as a design skill training program or tutorial. Most of the hard skills people can learn from either YouTube or other online platforms. It takes time to practice. We want to share with students the design process and how to apply it to solve these unknown, systemic or complicated challenges.

I feel I learned more than I teach to my students. The 7-day crash course experience has given me three learnings mixed with design inspirations and personal reflections about 1) design research, 2) system thinking, and 3) service design for longevity.

Learning 1. Design research is to re-search not for validation, but for inspiration

We all know that fieldwork is critical to projects as a source of input. It’s also a great opportunity for designers to immerse themselves to think and behave in the shoes of others and observe peoples’ real interactions, authentic reactions, and relations in the context for us to capture the first-hand materials.

Usually, most people overlook the importance of design research before moving forward to design process, because it’s not easy and takes time and patience to capture the “evidence” in the field.

For designers, the term “design research” means we are not searching for validation; instead, we are searching for inspiration to broaden our thoughts to explore various possibilities before sticking to one solution.

Without having proper time and resources to invest in design research, it’s difficult to identify the real design challenges and understand the subtlety and desirability from our targeted users.

To better address target users’ pain points, designers need to act as ethnographers to pay much more attention to details to “see” the motivation of people’s behavior and their purpose of decision-making, to listen mindfully to what people don’t say instead of what they said.

Otherwise, most of the time we can easily jump into the trap that designers tend to design products for themselves without awareness of the real-life situation.

Learning 2. Combine Human-Centered Design (HCD) with System Thinking (ST)

To me, the most valuable part of applying HCD is understanding targeted users’ needs and pain points to help us paint the close-to-real-life scenarios accordingly.

When students come up with preliminary design solutions, the excitement easily guides them toward solving very specific pain points to meet the expectations of the targeted users in the early stage of design process. Most of the time this is a very easy, effective, and direct way to propose a short-term solution with tangible outcomes. But we need to be mindful that we might lose the long-term considerations and to further think about the scalability of the design solution in a bigger context.

Real-world problems are usually much more complicated and systematic beyond our imagination such as how to renovate Taipei City Metro Station system to make it optimized and human-centered or, for a more extreme example: how might we design a space station on Mars?

Such challenges are impossible for a single designer to solve. There are more aspects that we should take into consideration, such as cultural differences, governmental policies, digital transformations, systematic problems, risk management, and emerging technologies.

Using HCD combined with ST approaches has played a critical role in the era of facing socioeconomic or social-technological challenges.

Some research has already promoted the concept and frameworks of Human-Centered System Design (HCSD). This ties to another important lens: D4L and service design.

Learning 3. Fluently apply service design for longevity

In the course, we guide students to identify the problems through the lens of longevity and service design.

Thinking in services has naturally extended designers’ views from focusing on the static product design to the service designs around products, since we consider the critical element of time to reshape the dynamic status.

For example, when we redesign a bar experience for a first-time visitor versus an old and loyal customer who has been in the bar for 4-5 years is a completely different conversation. A fresh customer might care more about the overall environmental design, the vibe of the space, or the brand of the drinks, whereas an old customer might have already built a close relationship with the bartenders. So the motivation for him/her to come back to the bar is to enjoy conversation with bartenders not just for a drink.

Regardless of what types of design challenges such as public transportation, product innovation, or policymaking, when I design services for longevity, keeping the element of “time” in mind is critical. Time is the fuel of the user journey, and it will seamlessly connect not only “when,” but also “who,” “where,” “how,” “what,” and ultimately the root cause of “why.”

Service design for longevity is a time-dependent and context-driven creative process. It requires cross-disciplinary knowledge and expertise to help us consider complicated challenges strategically, systematically, and purposefully.

Especially service design for longevity is the key to coming up with an inclusive series of solutions that are dynamic, flexible, adaptable, and adoptable to various scenarios and conditions.

Summary: The vision of building an AgeTech city lies in user-friendly and age-friendly social infrastructure

I had a great short trip back to Taipei and deliver this short and intense course with my colleague, Professor Sofie Hodara and MIT AgeLab. We designed the course and used Taipei Mass Rapid Transit as a case study to explore the public transportation system and design across products, services, and experiences through the lens of service design for longevity.

During the course preparation and in-person fieldwork, we humbly knew that we had so much room to improve to build an age-friendly city and environment for our society.

Even before discussing the term AgeTech or applying any emerging technologies, are we ready to implement and embrace user-friendly and age-friendly social infrastructure? Are we willing to change our mindset and behavior preparing for super-aging society transformation?

Acknowledgement

A lot of preparation and hard work had to happen for the 7-day summer course at Shih Chien University (SCU). For the great support and trust, I especially thank Dr. Joseph F. Coughlin, Founder, and Director of MIT AgeLab. Thank you to Professor Sofie Hodara, Northeastern University College of Arts, Media, and Design, who co-designed the course materials and co-taught the course with me.

Thanks to Vice President and Professor Tony Kuo, SCU International and Cross-Strait Affairs, for making the course happen with great support and encouragement from his team: Chair and Associate Professor Chien-Kuo Li, SCU Smart Service Management, Professor Ming-Hung Hsieh, SCU Graduate Institute of Creative Industries, Andy Liu, and Ian Wang.

I also appreciate SCU faculties from the Department of Industrial Design: Dean of General Affairs and Associate Professor Hsu-Cheng Chu, Associate Professor and Chairperson Sally Lin, Associate Professor Wan-Ru Chou, Associate Professor Chen-Hui Lu, Assistant Professor Shi-Kai Tseng, and our 32 summer course participants.

Reference

- MIT AgeLab

- Shih Chien University course

- Taipei Metro

- Service Design in Action: Transformation, Consideration, and System Thinking

- Applying Human-Centered System Design to the Development of a Tool for Service Innovation

- Experimenting with Design Thinking and System Engineering Methodologies: Using a Commercial Cislunar Space Development Project as an Example