Transforming Intuition into Innovation: the role of AI and Grounded Theory

Creative intuition doesn’t emerge from a vacuum and can be seen as an art form that bridges design and research.

Before the fall semester begins at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in early September, as the weather cools and life become busier, I take the opportunity to jot down my thoughts on the connections among creative intuition, daily observation skills, artificial intelligence (AI), and grounded theory (GT).

I have a personality that thrives on sharing my intuitions and initial thoughts with the team, whether during meetings, in discussions, or through emails intended to inspire. These intuitions and ideas are rarely perfect; they are often fragile and often might contain significant flaws.

However, these early, imperfect thoughts can serve as a catalyst, sparking more provocative and imaginative ideas from others with diverse backgrounds, particularly in the early stages of the product design and development process (Figure 1). The accessibility and potential of creative intuition are what captivate me. In this article, I want to share four key insights into my understanding and perception of creative intuition:

Creative Intuition

Daily observation enriches creative intuition

I’m inspired to explore the concept of “creative intuition,” a term I first encountered through Professor Kevin Gatta at Pratt Institute. It took me back to my time working at IDEO and Continuum, where I often questioned the conventional approach of starting projects with user interviews or fieldwork.

I understand this perspective might seem counterintuitive, especially considering what’s typically taught in a Design 101 course. Yet, in some client projects, I could almost anticipate certain solutions from the very beginning. These weren’t traditional design solutions but rather scenarios where users might face specific challenges.

This foresight wasn’t incidental; it stemmed from my practice of daily observation. I frequently took photos of things that amused or inspired me, often without fully understanding why I felt compelled to capture them.

For instance, while working as a designer in residence in Pforzheim, Germany, I spent three months photographing scenes during my morning jogs. I documented these photos with notes, questions, and ideas, turning them into a photo diary. This diary became part of my deliverable as a designer in residence (Figure 2). I didn’t realize that, in those moments, I was practicing, training, and strengthening my “creative intuition” muscle.

The power of creative intuition lies in the subtlety of your observational skills in everyday life. Can you discern the nuances in people’s body language? Can you sense the dynamics in a conversation? Do you resonate with others’ stories? Are you able to fully engage in activities with others through multiple senses?

I believe in the value of designers’ gut feelings, which are deeply rooted in our life and work experiences, learning process, and communication capabilities. These elements serve as essential nourishment for our creative intuition.

I had four books that I returned to frequently: Seeing Things, Ways of Seeing, Thoughtless Acts?, and Just Enough Design. I revisited these works often to remind myself of the value and importance of honing our observation skills in life.

Seeing Things: A Kid’s Guide to Looking at Photographs by Joel Meyerowitz (2016): Meyerowitz uses simple, memorable language and impactful visuals to present 30 essential principles of photography, including eye contact, seeing the light, watching and waiting, beautiful chaos, still life, dreamscape, looking into future, and the frame within the frame.

This book isn’t just about photography; it’s about how we can better develop sophisticated observation skills and cultivate them over time.

Ways of Seeing by John Berger (1990): This classic work on art explores how Berger viewed paintings and artworks, significantly influencing how we look at images. The book’s value extends beyond the arts, encouraging us to view the world through diverse and inclusive lenses. It inspires curiosity about our environment, people, and the things around us.

Thoughtless Acts?: Observations on Intuitive Design by Jane Fulton Suri (2005): This small book is filled with everyday observation photos from the street, kitchen, home, community spaces, and more—places, items, and behaviors we often take for granted.

Suri, a pioneer in design research who introduced ethnographic methods to design, highlights the power of these “thoughtless acts” to reveal subtle yet crucial ways people respond to their environments, even when their needs aren’t perfectly met. This approach offers a common-sense method that can inspire both designers and anyone interested in creative journey.

Just Enough Design: Reflections on the Japanese Philosophy of Hodo-hodo by Taku Satoh (2022): Satoh, a contemporary designer, applies the ancient Japanese concept of “hodo-hodo,” meaning “just enough,” to his design. His ideas resonate not only with designers but also with individuals who value thoughtful, sustainable lifestyles.

Hodo-hodo design maintains a deliberate distance, allowing space for individuals to engage with objects according to their unique sensibilities. This “just right” attitude evolves from fostering creative intuition to building a philosophy that can extend its impact from the self to families and communities.

Artificial intelligence can expand creative intuition

With the advent of AI and other emerging technologies, generative AI tools, such as Midjourney, DALL·E, Adobe Firefly, Leonardo.ai, OpenArt, and PromeAI, have made it possible for both designers and non-designers to generate countless ideas in seconds.

For instance, I utilized Leonardo.ai by entering the prompt “Creative intuition in design, no figure, process driven.” I then adjusted the settings on the side panel, selecting a presentation style of “sketch in B&W,” enabling “auto” for prompt enhancement, choosing “fast” for generation mode, setting the image dimensions to 16:9, and requesting four images.

The resulting images can be seen in Figure 3. Additionally, the prompt details provide a comprehensive description of these generative images:

“A highly expressive, abstract pencil sketch of creative intuition in design, capturing the dynamic process of idea generation, sans figure, with bold, expressive pencil marks that dance across the paper, revealing subtle texture and natural fibers, conveying a sense of organic spontaneity, with a mix of sharp, pointed lines and soft, blended shading, evoking a sense of tension and release, set against a warm, creamy paper background, with a subtle grid pattern, hinting at the underlying structure of the design process, and nuanced play of light and shadow, which imbues the composition with depth and intrigue.”

This has created the illusion that the idea-generation process—even if not always yielding good ideas or effective brainstorming—is now easily accessible to everyone.

However, accessibility does not equate to ease in creativity, nor does it mean that generative AI tools can produce high-quality design solutions. While we may now have a flood of ideas, the real challenge lies in selecting the right ones. Beyond that, can these tools enhance our taste or even transform our lifestyle?

“Maximization” may be advantageous at certain stages of the design process, but that doesn’t mean the entire process should be maximized. In some cases, “optimizing” might be the better approach, particularly in how we express and pace ourselves, curate life experiences, and cultivate a sense of belonging.

Life experience isn’t about being glued to social media 24/7 or confining ourselves to the office to live predictable lives. It’s about opening our hearts and minds to the world—through seeing, listening, touching, experiencing, feeling, and even meditating.

AI is a double-edged sword, depending on how strategically we apply it as a support tool during the creative process. If we rely solely on generative AI solutions without careful evaluation and modification, we risk stifling individual creativity.

On the other hand, when used wisely, these generative AI tools can accelerate the design process, expand our problem-solving capabilities, and help translate creative intuition into provocative research insights. Ultimately, they can lead to implementable innovative solutions across different levels of products, services, and experience design.

As generative AI tools become more widely adopted in design, the “design-to-customer (D2C)” concept introduced by Jonathan Olivares in 2012 is supposed to evolve significantly. Enabled by the Internet, the D2C model bypasses traditional distribution costs, allowing designers to sell fewer items at higher margins than conventional manufacturers.

However, in the era of AI, the D2C model needs to become more reciprocal, as consumers are no longer passive recipients of design solutions from professionals. Instead, they are increasingly empowered to use these generative AI tools to ideate, suggest, and even produce customized ideas that cater to their needs, supported by accessible fabrication technologies and global supply chain networks.

How can we connect generative AI tools to creative intuition, and why does it matter? I don’t have a definitive answer yet, but I believe that utilizing generative AI tools can efficiently populate our ideas and expand the boundaries of research topics. They can supercharge our provocative thoughts, and, with careful consideration and purposeful integration, help build our creative intuition.

Constructivist grounded theory can uncover emerging themes from and within creative intuition

Due to my research project on longevity services, which involved qualitative descriptive research, I began learning and applying constructivist GT as outlined by Kathy Charmaz (2006) in my service design work.

Grounded Theory (GT) is not a new qualitative data analysis method. Since its introduction in The Discovery of Grounded Theory by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in 1967, various types of GT have emerged.

These include classical GT by Barney Glaser (1978, 1992), which emphasizes discovering codes within context with flexible and adaptable approaches, procedural GT by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin (1990), which advocates a more rigid procedural coding process, and constructivist GT by Kathy Charmaz (2004, 2006), which blends elements from both classical and procedural GT.

Constructivist GT is a powerful qualitative data analysis tool that fragments data into codes. For example, it can be applied to a typical interview video transcript for qualitative data analysis, offering designers and researchers a fresh perspective on engaging with data.

The first step is initial coding, also known as open coding, which helps us “open up” the conversation by labeling individuals’ motivations, actions, and processes within the transcripts. This step is like descriptive coding and serves as a foundation before moving to the second step, focused coding, where initial codes are selected and clustered.

The aim of constructivist GT, as with other types of GT, is to discover, identify, analyze, and synthesize emerging meanings throughout the coding and decoding process.

Constructivist GT is a method applied and evolved in the process, not for the process. This gives designers and researchers more flexibility to co-construct the meaning of initial codes, focused codes, axial codes, and thematic codes.

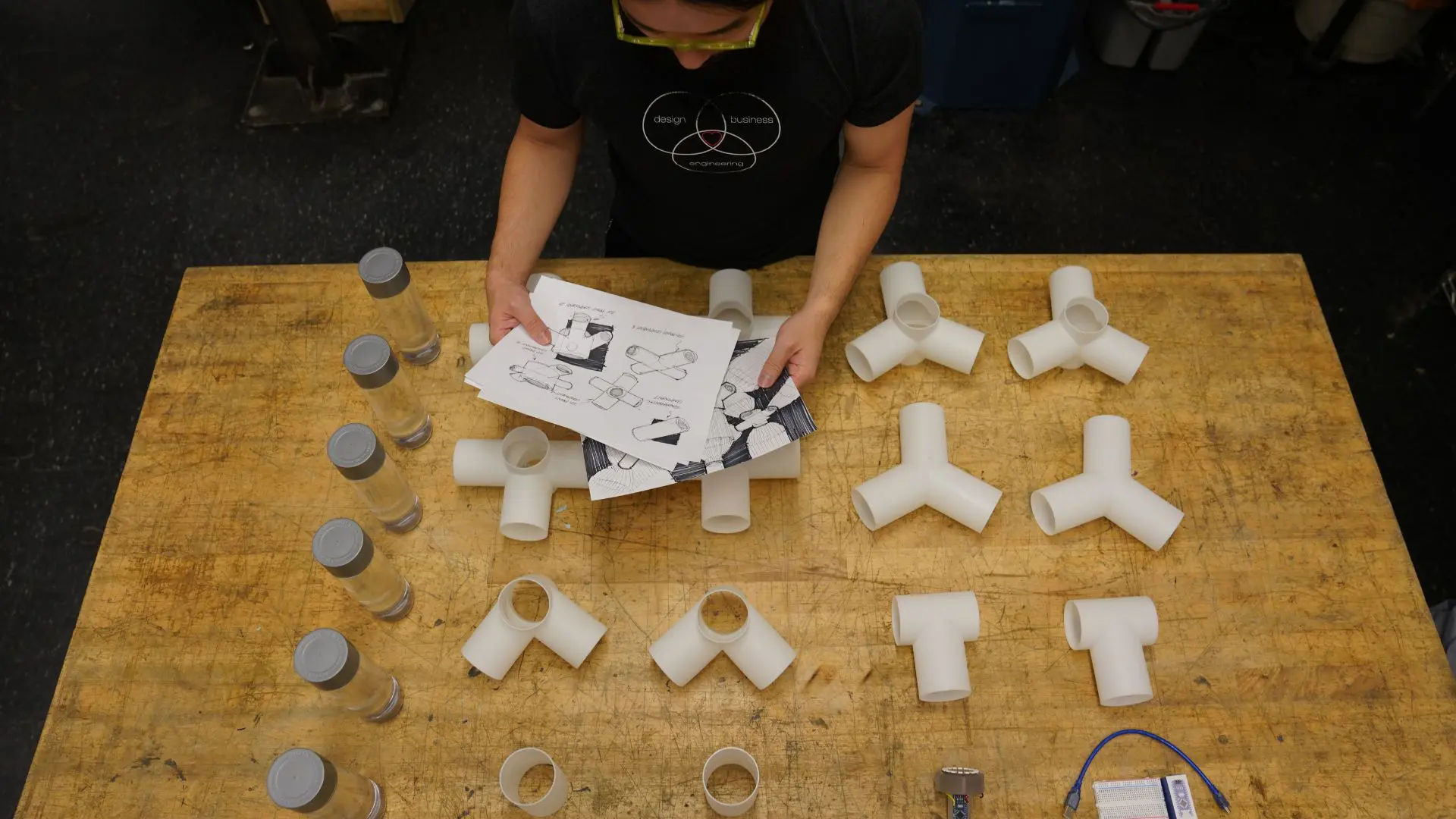

Incorporating constructivist GT into the design process has led me to reflect on the role of a designer’s creative intuition and the working environment in design consulting. During my time at IDEO and Continuum, I appreciated how each project created its own project space (Figure 4).

We captured our in-field learning and “downloaded” our key takeaways by encouraging team members, including designers, clients, and sometimes participants, to write or draw their initial thoughts, observations, interviewee quotes, client feedback, personal reflections, and even doodles on Post-its to share.

This process of downloading, briefing, and synthesizing closely mirrors the application of constructivist GT in work and physical environments. Throughout, team members actively shared their “creative intuition.”

Creative intuition does not happen in a vacuum. The curated project space, the immersive discussion environment filled with observation photos and Post-its, the field research experiences, the team dynamics, the supportive leadership, the open communication style, and the overall culture all influence the quality of our creative intuition.

From my personal experience, strategically applying constructivist GT can enhance both the quality and quantity of creative intuition. It allows us to fragment and reconfigure data, constructing meaning and expression in ways that enable us to comprehend, craft, appreciate, and share stories through multi-dimensional aspects, thereby reinforcing creative intuition.

Creative intuition doesn’t arise in a vacuum

Creative intuition doesn’t emerge from a vacuum and can be seen as an art form that bridges design and research. I consider it a skill that can be cultivated, practiced, accumulated, and refined through life and work experiences, individual frustrations, delightful stories, and interactions with colleagues.

In this article, I explore the benefits and drawbacks of using AI experimentally to broaden the scope of our creative intuition. I appreciate the redefinition of AI as “anticipating intelligence.” By engaging in more immersive and intentional anticipation, intelligence can emerge and nourish our creative intuition.

We also discussed applying constructivist GT to uncover emerging ideas from and within creative intuition. The iterative process of coding, decoding, grouping, and clustering creates an open platform for designers and researchers to discover new creative potentials for design solutions.

Another aspect of creative intuition is that I don’t see evidence-driven approaches or qualitative data analysis methods as conflicting with design-driven methods or creative processes. Both provide different frames of reference for observing study objects or focus areas. Designers need to develop both capabilities to gain comprehensive and inclusive perspectives before making decisions and executing ideas.

When someone says, “I have an idea…,” I listen carefully and usually jot it down on a Post-it from my pocket. I value and respect these early thoughts, especially because they keep me curious and motivated to translate this shared creative intuition from idea level into insights, and, with luck, into implementable innovations for future product design and development (Figure 5).

References