Creativity is overestimated (unless you know what to do with it)

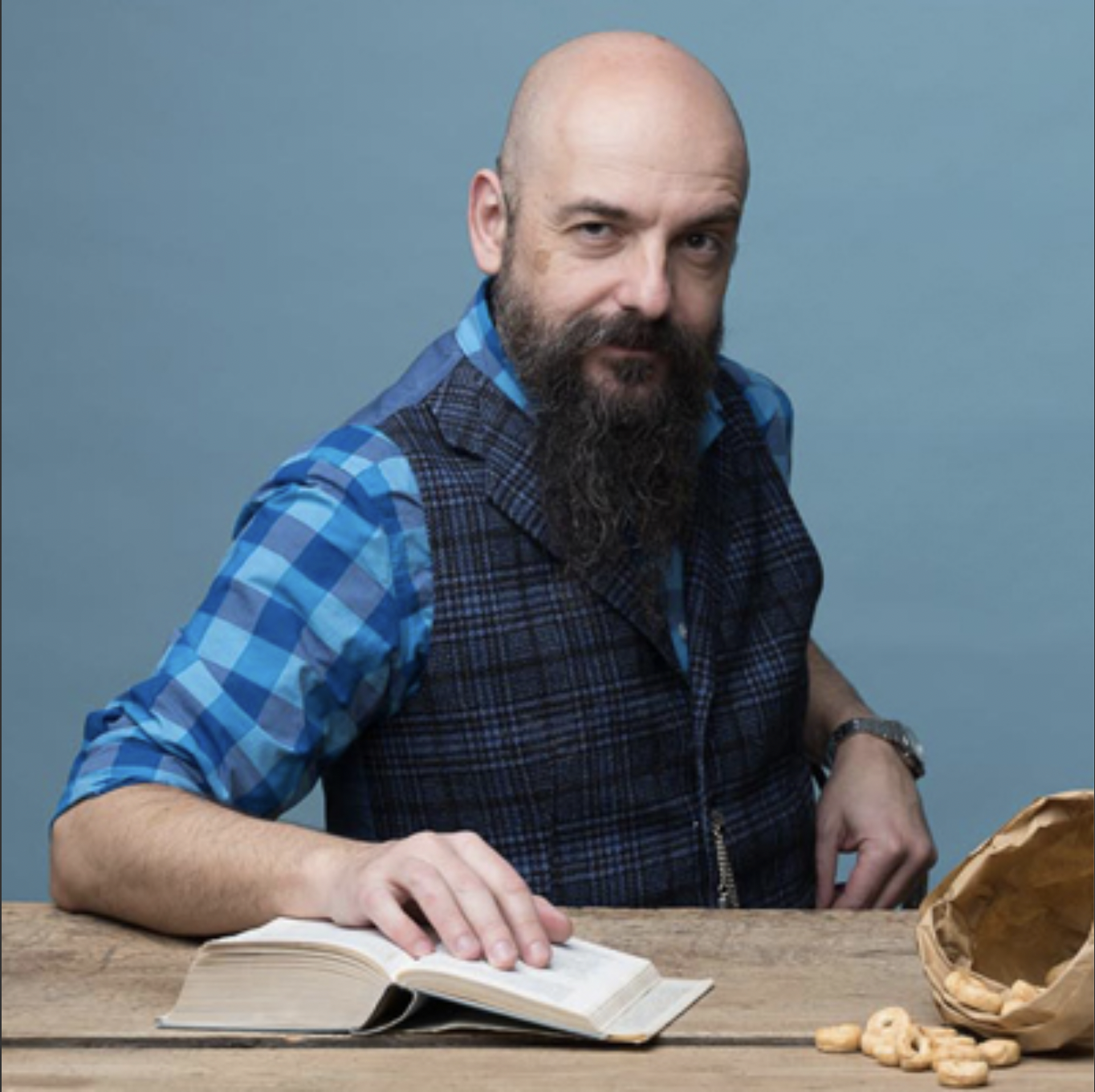

Many years ago, in 1999, I listened to a Ron Arad lesson at the Domus Academy in Milan.

I remember a darkened room, Arad wearing his incomprehensible furry hat with earmuffs and the silence that fell on the audience when he said: “You think ideas have a great value but

ideas are worth nothing.

Anyone can have ideas. What matters is what you are able to do with them”.

I don’t know what students brought home from that talk because no-one commented on what Ron Arad said.

For me, though, it was one of the most correct and useful statements I had ever heard from a teacher.

Creativity has become a totem that we all venerate

The reason why Ron Arad’s statement was so troubling is that creativity is venerated (and no-one ever discusses its value). When did this happen?

When it comes to contemporary design, it probably all started during the social revolutions from the late Sixties but was further developed through the epic times of commercial communications in the 80s: when fashion and design became “a thing”.

While now, in the era of social media, creativity is often described as a state of grace: a light – the big idea – coming from above.

Creativity, with no other attributes, creates frustrated people

This type of creativity, though, is overestimated when it’s not supported by other qualities and attitudes. These can belong to the same person or to others within the same team.

Ron Arad was right: an idea, when you don’t know what to do with it, is worth nothing.

Worse: creativity, when it’s not supported by other qualities, turns into frustration and

it produces people who feel misunderstood by society, undervalued and unrewarded

(also economically) as they believe they deserve.

If this is the price to have good ideas, then it’s best not to have any!

The idea is an oxidiser. In its absence there is no flame, but to have the flame you also need fuel, and there are many kinds of fuels

just as there may be many ways of applying the same idea in a fruitful way.

Finding a place in the world for your idea

Thus whoever has an idea also carries the responsibility of finding a place in the world for their idea.

This passage can occur within your own head or through dialogue with others, remembering that in a complex world like ours:

- teamwork, rather than solitary invention, is always a winner

- an idea is worth when it creates a fruitful dialogue with its social, technological and cultural context

The history of design and technology is dotted with beautiful original ideas that remained in a drawer or victims of very short commercial successes, as well as intuitions that built empires based on ideas that were not entirely new or original.

Apple: an empire built on excellent timing (but not on entirely original ideas)

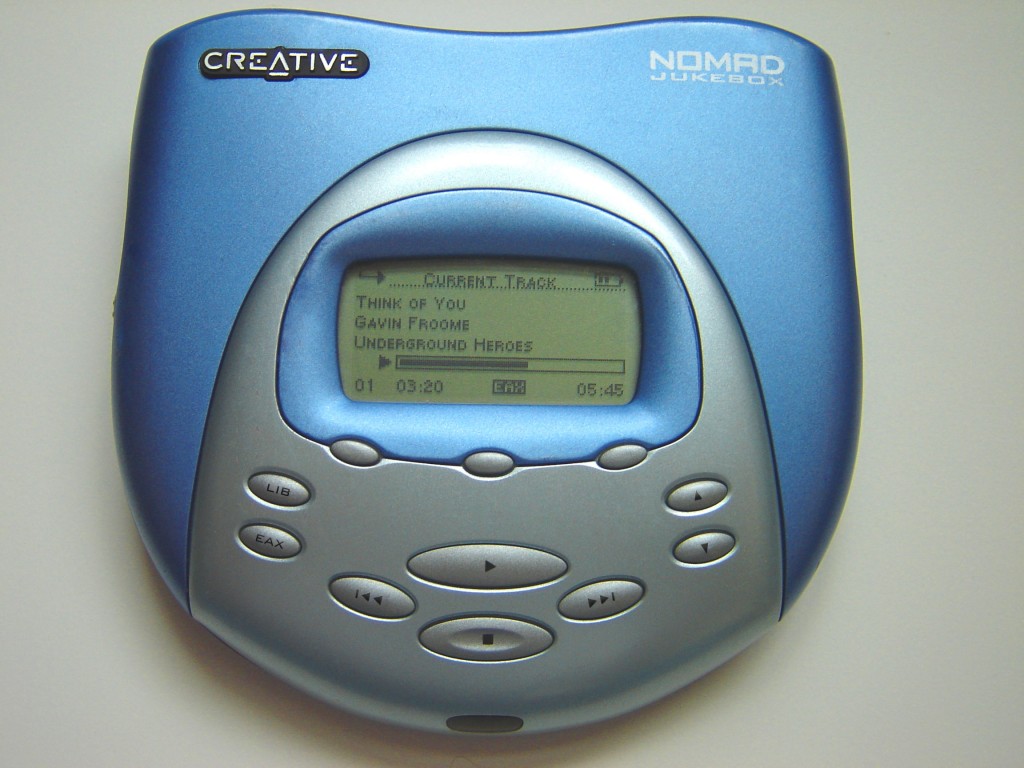

Speaking of technologies that are now vintage, the idea of digitizing music and listening to it through a solid state device is commonly associated with Apple and its iPod.

Yet other brands produced and marketed portable mp3 file players before them.

Those companies had the great idea: making people able to listen to thousands of songs anywhere, without having CDs or audiotapes at hand.

They were not small players: the first MP3 player was marketed by South Korean Saehan Information Systems in 1998, followed by giants like Sony, Bang & Olufsen, Intel and small but very “cool” Singapore brand Creative Lab.

So why were those companies unsuccessful?

Simply because they were

unable to couple an object with a supporting digital ecosystem and to imagine a product that did away (totally) with the past.

The first mp3 player I had in my hands, for instance, was the Nomad JukeBox by Creative Lab, and it was shaped as a portable CD player.

Despite being a thoroughly revolutionary product, it lacked the charm, the novelty, the visual appeal that said: this is where the revolution starts, join it.

Apple, on the contrary, had built all of these elements perfectly: the sensual, space-age-like product, the digital framework to fill it up with contents, the smooth interface, the powerful storytelling.

The result was a global success, which lasted until the technology was overtaken by the spread of smartphones.

Channel creativity through MAYA (and a roadmap of ideas)

MAYA “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable” is still the principle to consider every time you start from an idea and try to give it life.

The starting point has to be good, but the company that you address must be able to understand the benefits of the proposal. Both of you need to figure out what is correct to launch now and what, on the contrary, requires some preparation for the public.

Take wearable devices monitoring health.

25 years ago I participated in a research that evaluated the possibilities to develop devices that analyze our vital functions.

When confronted with the idea, a sample group of elderly people told us, in an absolutely solid way, that they would never wear something that monitored their biological values and functions, even if that could improve their safety.

Now the smartphone + smartwatch combo knows everything about us, using data partly to help us, partly to flood us with ads.

The smartphone is an almost indispensable object, while the smartwatch is widely accepted, and often the new object of desire for those who love sports and technology.

What’s the lesson to take in? That

if a great idea needs time for acceptance, you should have some other great ideas – a roadmap – that leads people there.

Visualizing what the future could be like, insinuating feelings of what tomorrow may be.

Which is, for instance, exactly what Meta is doing now with the metaverse: trying to make us feel for it so that we may want to actually get it in when they have it ready for us.

Which brings us to the next and last consideration.

Creativity is useful when it is limited to where it makes sense

Creativity is not an inexhaustible source of right and good ideas, it can also produce ugly, wrong, bad, useless, grotesque ones.

[ Read also Preventive Innovation: what it is and why we need it now ]

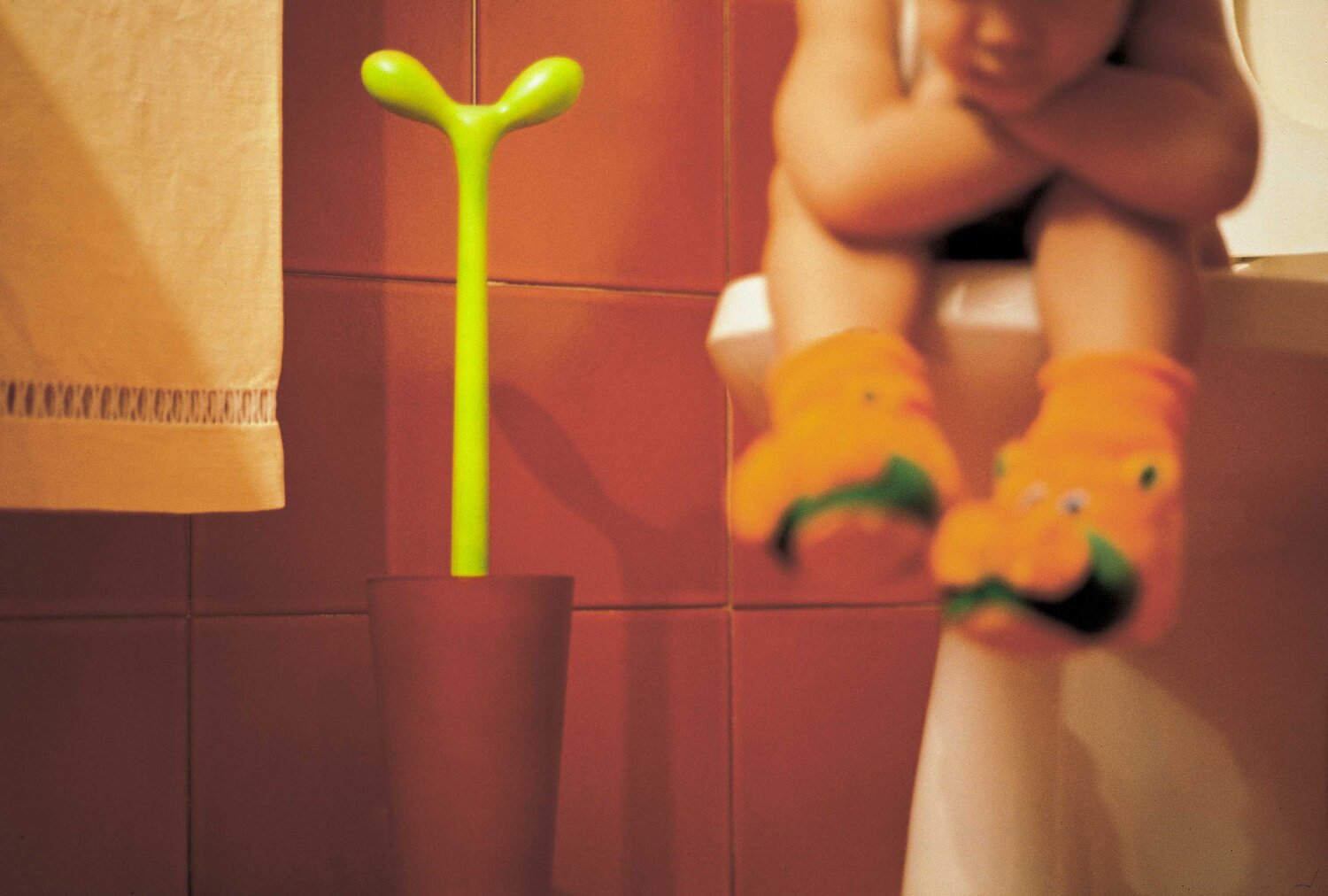

I’ve recently stumbled upon a design for a rotating, battery-operated, rechargeable toilet brush with a plugged-in stand, and I’ve also seen a static model of it.

It was an object that showed great creativity, but completely useless and too complicated.

Yet someone had spent months of work without seeing its limits.

Today I discovered that there are similar products on Amazon, but I’m pretty sure they won’t change the world, nor the lives of those who have to clean sanitary ware, and that they won’t be a great commercial success.

The only true idea of the last two thousand years, in the field of toilet brushes, belongs to Stefano Giovannoni.

The Merdolino toilet brush that he designed for Alessi was the result of a design work focused on the meaning of the object. He made it look like a fun, friendly object that you wouldn’t want to hide.

He didn’t try to improve the form/function relationship: that was already perfect since ancient Rome.

Merdolino was a great success because the idea was limited to where it belonged and didn’t go any further.

Self-critical ability is the necessary enclosure to place around the fire of creativity, to govern it and direct it towards correct functions.

Unfenced creativity creates fires, painful for all. And, particularly, for the environment.