Design for simulation: how to project your future self?

Prototyping, simulating, and refining service design in Design for Longevity (D4L) context. Design for simulation is a critical step to help us refine the experience design before considering scaling the defined service offerings.

Recently, I’ve become passionate about the concept of Design for Longevity (D4L). D4L goes beyond discussing only design for financial planning or retirement. In fact, D4L can cover the essence of people’s lives, applying long-term thinking and sustainable actions connecting mobility, housing, transportation, policies, communication, entertainment, food, and many other aspects.

In the era of transformation, with everything changing relatively fast and unexpectedly, how do we effectively and meaningfully not only design and curate user experiences, but also simulate immersive service experiences to evaluate some early design hypotheses?

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

Essentially, D4L can be interpreted as not only designing things or tangible products for users for the long run, but also considering how to live a sustainable lifestyle with purpose, dignity, and delight. Whether or not we have a design background, we should ask ourselves one question: how can we project our future selves and quality of life through the creation of products, services, and experiences? To better respond to this question requires learning how to strategically simulate desired design solutions and processes in the future.

The terms simulation and prototyping are subtly different. To me, prototyping is to test mostly ideal concepts from designers’ perspectives, whereas simulation is to test ideas from actual users or designers considering more real-world factors such as actual testing locations, physical or digital spaces, human-computer interactions, economic conditions, policies, curated service scripts, and even weather or climates.

Two simulation models for game-based learning and user experiences

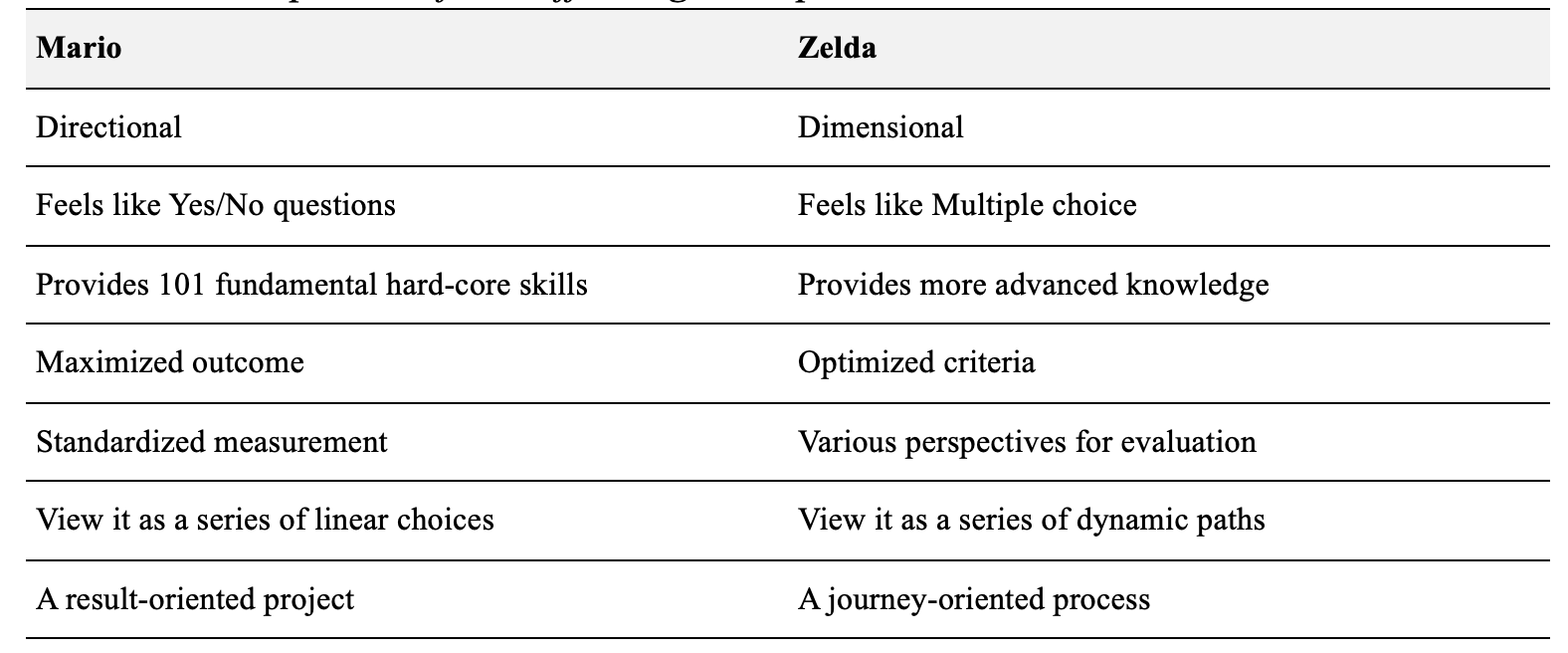

When we were kids, we played video games such as Mario and Zelda. Let’s look at them through a game-based learning lens. Mario is a video game to simulate players always “going right.” It’s a one-directional path to solve challenges. The user experience is created as a pre-defined journey.

Unlike Mario, Zelda is a video game to simulate players’ journeys in various dimensions. The game design provides multiple choices to create many surprising possibilities and dynamic paths, and its storyline and experiences are more like an actual journey.

These two games simulate or generate very different game experiences for players. I summarized these tensions in Table 1. This can inspire us to think about when we face more complicated service design projects, and how we break down our design brief and challenges into multiple layers and components to analyze and decompose them.

Design for simulation is a critical step to help us refine the experience design before considering scaling the defined service offerings. It is like designers or design companies coming up with brilliant products to solve problems, but before they submit the CAD models to manufacturing companies, they need to conduct a high-resolution prototype.

Design for simulation can also consider a part of live prototyping (Figure 2). I was part of the project team to redesign a 360-degree bar experience in Shanghai when I was in IDEO. I role-played as a bartender to engage with real customers to gather first-hand feedback.

Essentially, we wanted to explore experiences both from service providers (e.g., bar company, bartender, the operational side) and service recipients (e.g., customers or users) to envision its space layout design, food-pairing experience, a new flavor of draft beer, branding strategy and planning, business innovation and opportunities, and staff’s roles and responsibilities.

Before we conducted a live prototyping session, we learned from our clients how to behave and serve as a bartender for a week. It was challenging to remember all the different types of craft beer and service details in a short amount of time such as how to pour and fundamental bartender etiquette, and keep in mind the things we tried to test in live prototyping. Ultimately, we were not aiming for perfection in terms of the design components. Our goal was to design for the research experiment.

Let’s mapped some of service prototyping and simulation of a bar experience design project to my Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Ph.D. research project Design for Longevity (D4L) to apply the learnings and observation to rethink future financial planning services.

I experimentally took bar service design experience and apply some learnings and design principles to the finance field. How do we redesign financial planning services including people, products, and platforms to evaluate the experimental process and result?

Financial planning is a relatively sensitive and private conversation for most people, which makes this project much harder. When designing for simulation in a finance context, we need to take an extra human-centered layer of data privacy, ethical issues, and personalization into consideration.

We also need to come up with actionable and feasible plans to achieve a more real service design simulation. Normally, designing for simulation is not an easy task as we normally do in a typical design stage. It takes many considerations to generate the strategic plan for execution. My experience of design for simulation that I learned from the service design projects inspires me to share the following three recommendations:

Recommendation 1. Simulate service design prototyping by leveraging emerging technologies.

Prototyping service is not news in the design field anymore. And its concept is very similar to traditional product prototyping in the industrial/product design field. The difference is service prototyping needs to consider both tangible and non-tangible touchpoints across the journey. Some designers will apply service blueprints, modified journey maps, or role-playing to test the new service models in many rounds of interaction.

Satu Miettinen, Dean at the University of Lapland and Professor of Service Design, is a pioneer in service prototyping combined with emerging technologies such as applying extended reality (XR) and projection to build the designed and curated virtual-and-physical service experiences to evaluate design hypothesis more effectively.

Mari Suoheimo, Associate Professor in Service Design at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO) demonstrated X Laboratory to me and explained how these technologies can foster the speed and accuracy of service prototypes in a virtual world. For example, the big movable TV screen can quickly display different scenarios based on different research requests. Prof. Suoheimo also shared with me that in the future, the school wants to invest more budget and resources in virtual technologies to help collaborative clients simulate some of their early design rendering and results with real responses.

The beauty of service design prototyping lies in the complexity of various touchpoints including virtual and tangible touchpoints across the whole user journey (Figure 3). As designers, we need to learn how to leverage these emerging technologies to make an improvement and meaning by connecting the dots online and offline.

Recommendation 2. Consider service design simulation as another level of service prototyping.

Design for simulation is more than role-playing or result-oriented measurement to practice service design. Instead of conducting a simulation experiment, researchers or designers need to know how to follow the flow of conversation and identify the opportunities to jump into the discussion.

This is especially critical for service designers or experience designers, since they need to learn when and how to facilitate the conversation effectively and efficiently. For example, when we simulated D4L service experiences, we observed our participant’s reactions, both verbal and non-verbal.

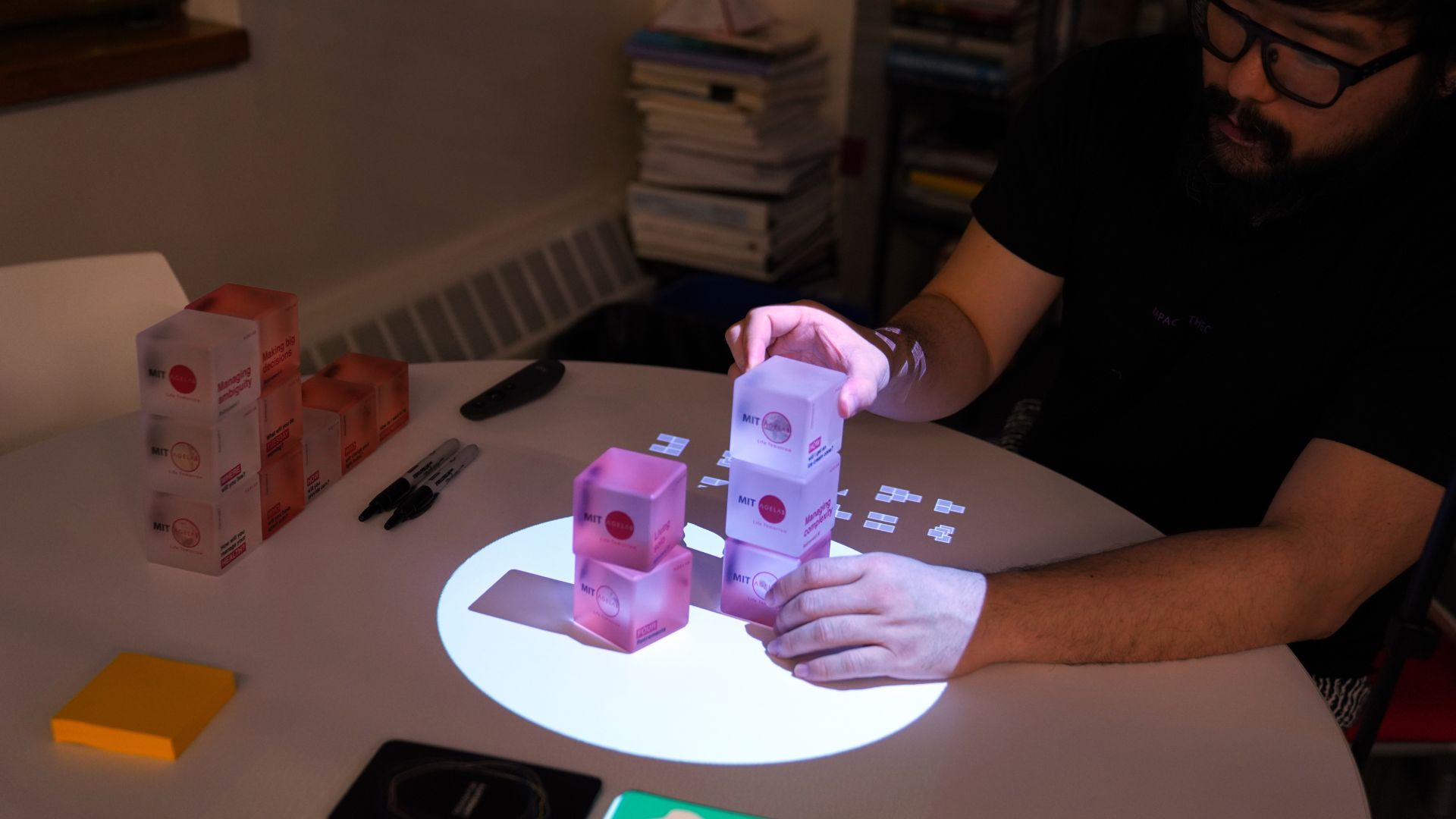

Figure 3 shows D4L cards we used to introduce different scenarios, allowing us to dig deeper to figure out why people selected specific stories that resonated with them in a financial context. Designers need to know how to remain neutral while conducting service design simulations. Designers might have a desired expected outcome before starting the service design simulation. How do we avoid biasing the result or process?

Another interesting thing we can talk about is how we document people’s behavior and discussion through documenting the service design simulation. Besides video and audio recordings, what are other approaches or interactive formats that we can use to capture scenes/scenarios or people’s authentic reactions to understand the vibes of conversation and environment?

Recommendation 3. Define creative measurement units for the service design process and outcome.

Measuring service design outcomes is also challenging. The term “figure of merit” is learned from and inspired by Olivier L. de Weck, Apollo Program Professor of Astronautics and Engineering Systems at the MIT, and his graduate course: Technology Roadmapping and Development.

A figure of merit is the measurable unit that helps researchers evaluate, compare, and analyze the experiment results, so, for example, velocity can be considered as the number of miles per time spent or volume can be viewed as the number of items per pre-defined space. It is a numerical or scientific way to view the world.

Besides measuring efficiency or effectiveness, what and how can we quantify the outcome or process of using D4L service experience? For example, while participants are playing with the cards, how many questions do they ask per hour? How many ideas do they come up with? How long does the discussion last? These might be more flexible “units” with which to view the quality of the card design.

How do we purposefully gather service design quality and experience together to discuss and analyze its effectiveness? What is the creative figure of merit that we can apply or define? Thus Prof. de Weck and I brainstormed an evidence-driven way to establish the evaluation metrics.

For example, in the D4L service experience project, we thought about giving our participants control over the slides (e.g., D4L interactive map) and then measuring how much time participants want to spend per slide. Or we might document how many questions are being asked or ideas are being generated per time unit (e.g., 30 minutes or one complete interview session). These are creative ways to envision how to scientifically measure the service design field (Figure 5).

Further research can test different measuring “units” to explore the criteria of usability in the context of D4L service experience, games or even play, which might also affect the desirability of participants, the viability of business or marketing, and the feasibility of emerging technologies.

Summary

The concept of design for simulation is in a constant dynamic stage under a series of prototyping experiments. In the article, we shared three best recommendations: 1. simulate service design prototyping by leveraging emerging technologies such as AR, VR, or XR, 2. consider service design simulation as another level of service prototyping, and 3. define creative measurement units for the service and experience design process and outcome.

In addition, design for simulation should take the real-life conditions into considerations, including human-computer interactions, economic social status, actual prototyping participants, physical or digital touchpoints, policies, curated service scripts, and even weather or climates.

In further studies, we can apply design for simulation to some potential applications or other analogous examples or extreme case studies that we can learn from, such as simulating design outcomes and measurement criteria for prisons, hospitals, emergency rooms, space stations, fire stations, or other places operating in extreme environments.

Acknowledgment

The Ph.D. research project is sponsored by MIT AgeLab and the article is inspired by Dr. Joseph F. Coughlin, Founder and Director of MIT AgeLab, and his recent longevity research. The examples are inspired by the MIT game design course (CMS.590) taught by Eric Klopfer, Professor of Comparative Media Studies at MIT. Lastly, the beautiful visuals and the financial planning interface was co-designed and co-curated by Sofie Hodara, Professor of College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University.

Reference

- MIT AgeLab

- MIT Ideation Lab

- The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing, Most Misunderstood Market

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity

- Stage (Not Age): How to Understand and Serve People Over 60 — the Fastest Growing, Most Dynamic Market in the World