Redefining norms: what extreme users teach us about design

Designing for extreme users demands a deep sense of empathy to uncover hidden needs and challenges. This includes groups that are often physically vulnerable and require additional care and support.

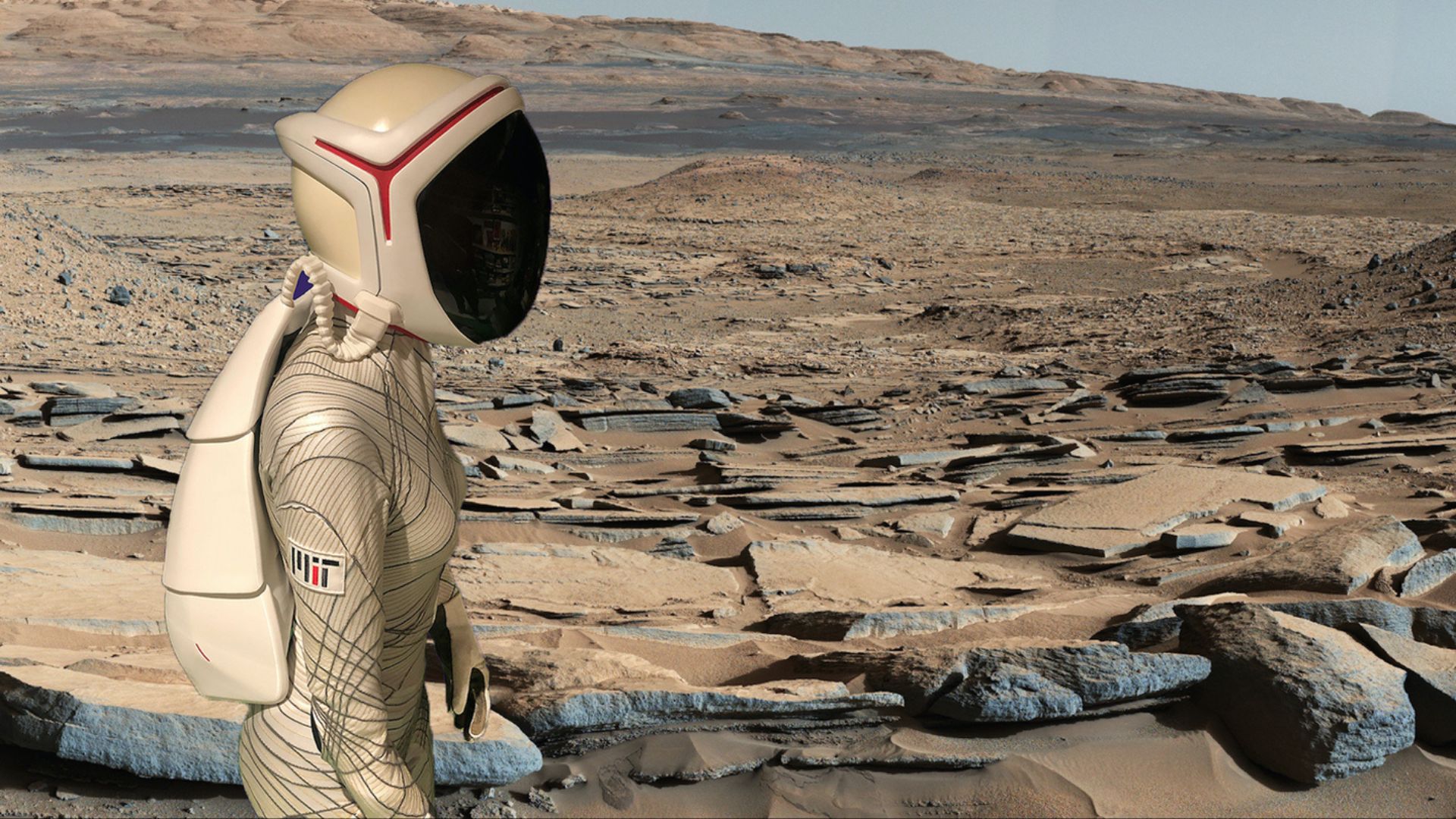

Recently, my friend Devin Liddell, a designer and principal futurist at TEAGUE, and I embarked on an intriguing project: designing a space travel system tailored for the aging population (Figure 1).

Why space?

Space continues to captivate us with its vast unknowns and mysteries, offering countless opportunities for untapped science, technology, engineering, and design innovations. These possibilities inspire me as a designer to dream and create in this context of an extreme environment.

Why focus on the aging population?

Actually, I should use the term “extreme users.” I see both the aging population and children as extreme users—individuals who are physically more fragile and often require additional support. Designing for them demands a heightened sense of empathy, revealing needs and challenges that might otherwise go unnoticed. This brings me to two preliminary ideas that inspire me to write this short article:

- How can we champion human-centered design in an extreme environment, such as space exploration?

- What insights can we gain by observing extreme users—their behaviors, interactions, and responses to products and services?

Reflecting on this concept of designing for extremes, I’m reminded of the wisdom shared by Professor David Wallace of the MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering in his course: Product Engineering Processes (2.009).

He articulated seven principles for design, teaching, and aspiring for excellence: 1. everything is an example; 2. have a plan and be ready to change it; 3. make students’ starts shine; 4. everyone has something to teach; 5. goals are essential; 6. play seriously; 7. the euphoria of growth.

These principles resonate with the core philosophy of human-centered design (HCD), which prioritizes addressing fundamental human needs. Designing for extreme users is a natural extension of this approach, offering valuable insights into the diverse ways people interact with the world. Through this exploration, I’ve uncovered three key learnings that I’m eager to share with you:

Extreme Users – Three key learnings:

Analyzing extreme users can help us understand the motivations behind their decisions and distinctive lifestyles.

During my time at design consultancies IDEO and Continuum, I gained valuable insights from interviewing small groups of five to seven “extreme users” recruited from HR. These interviews were often inspiring, as their stories about what they liked or disliked and how these preferences connected to their lifestyles revealed profound insights.

Why limit the interviews to just five to seven extreme users? Why not involve more participants in client projects? One reason is the time constraints of typical projects: most last two to three months, with design sprints often compressed into just two to three weeks. Additionally, project teams are usually small, often consisting of only three to four members, including myself.

More importantly, extreme users provide significant value because of their clarity about what they want or don’t want. Their strong opinions and detailed stories often amplify our understanding of why specific products or services resonate with them more than others.

At MIT AgeLab, when I conducted 81 in-person experiments and semi-structured interviews on longevity planning services, I categorized participants into three age groups—adulthood (25–54 years), pre-retirement (55–64 years), and post-retirement (65–84 years)—based on factors like pre-tax annual household income, assets, and gender.

The post-retirement group can be identified as the extreme user group if we consider age as a defining factor among these three groups. However, in this case, based on their income and assets, I would also classify these three groups as distinct types of extreme users.

After the interviews, I also evaluated whether participants were like boundary-pushing users or key opinion leaders (KOLs). Observing their reactions to the concept of longevity planning provided fascinating insights, particularly through the words they used, the stories they shared, the questions they asked, and their engagement levels, such as how often they interacted with tangible artifacts during the experiments and interviews.

The stories and interactions of extreme users revealed diverse perspectives and rich layers of knowledge, helping me better understand the complexities of longevity planning services. The next challenge was how to identify their motivations or implicit behaviors?

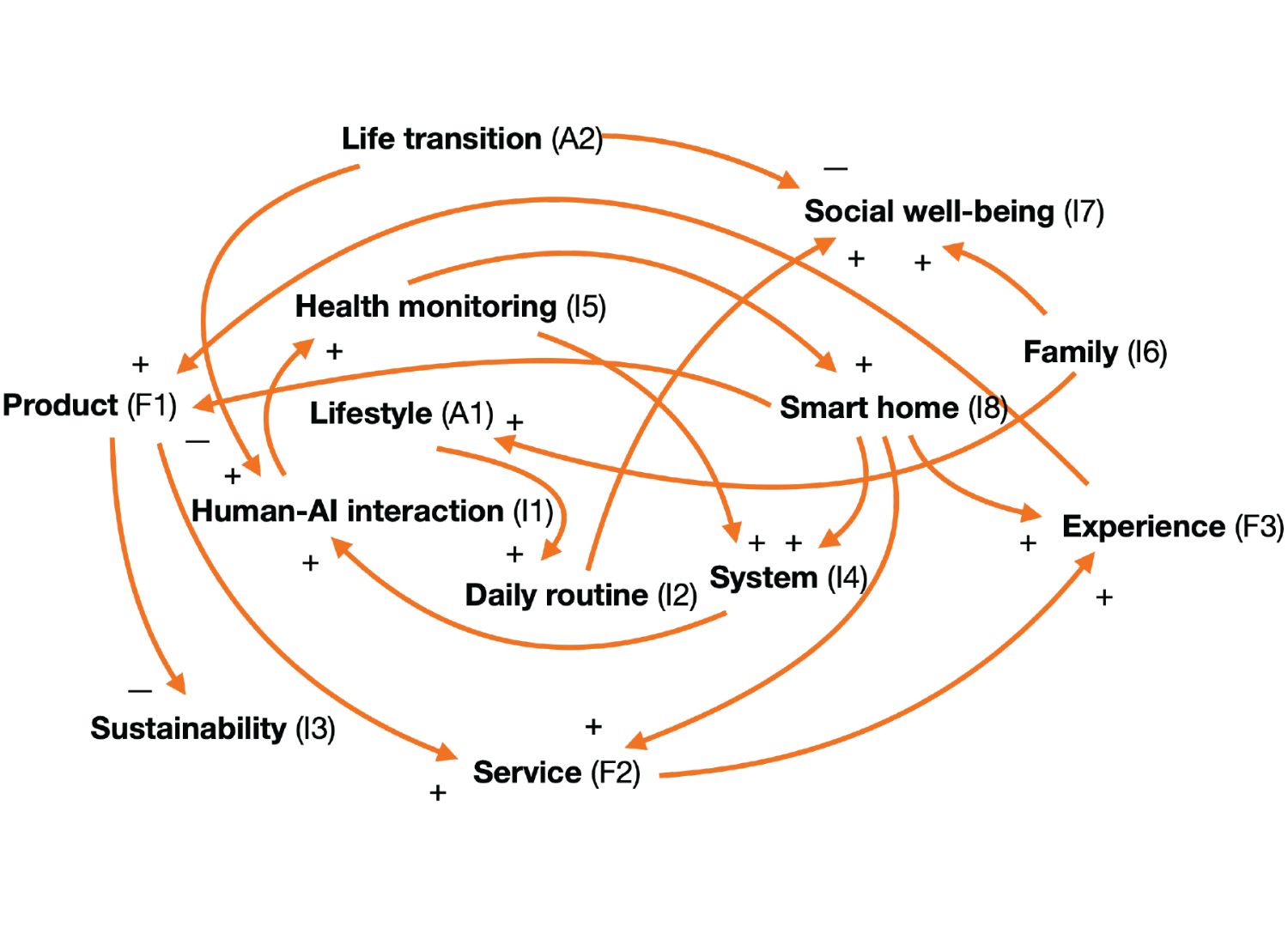

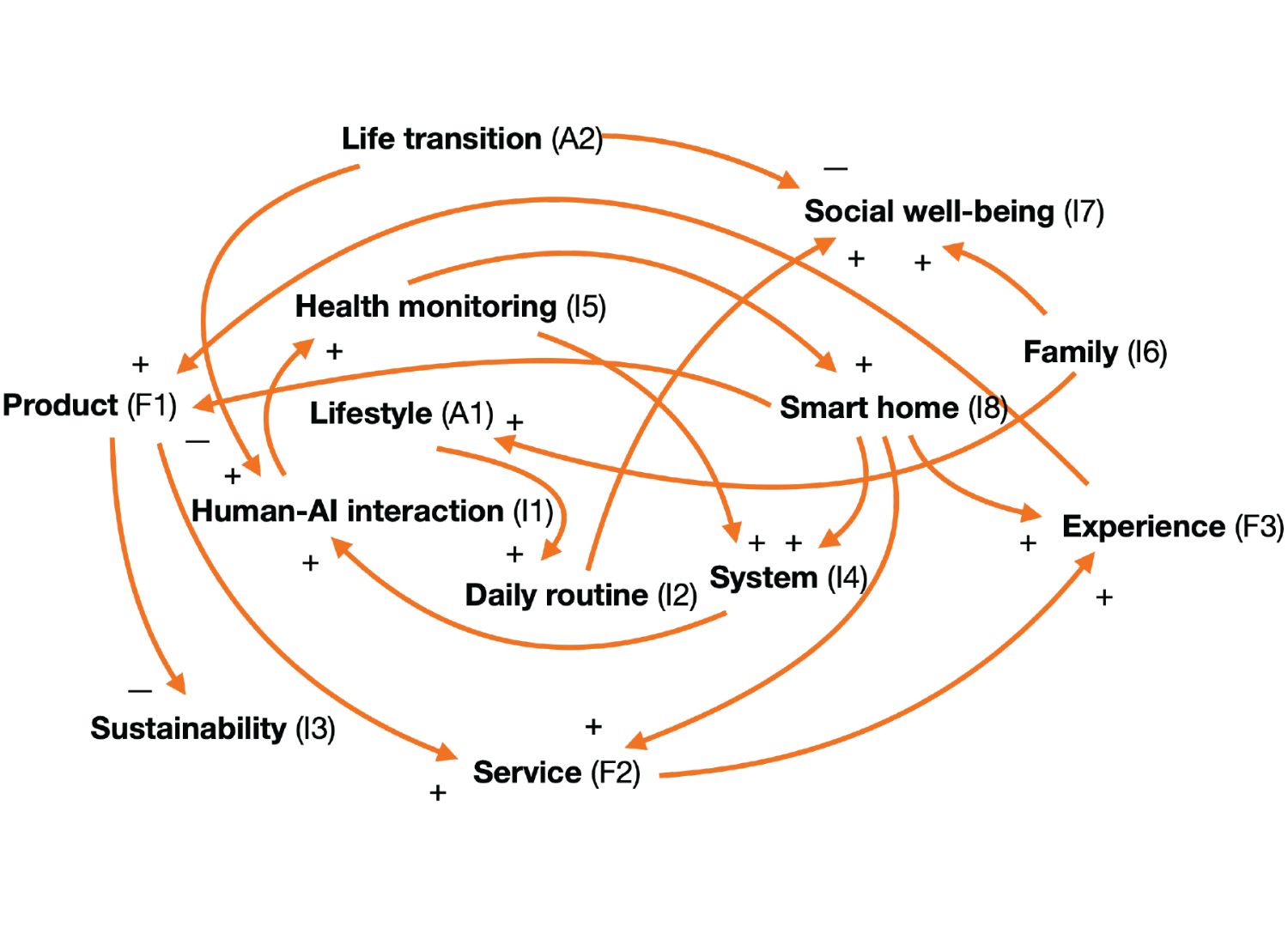

To address this, I applied system modeling tools, such as causal loop diagrams (CLDs), to map the longevity planning service systems (Figure 2).

Using qualitative interview transcripts to develop codes by applying constructivist grounded theory involves an interactive, constant comparison process translating from video transcripts, sentences, and words to codes.

This approach allows me to categorize and transform these codes into three types of variables—endogenous, exogenous, and excluded—and establish cause-effect relationships among them. Positive (+) or negative (-) valences were added to represent whether the relationships formed reinforcing or balancing feedback loops or specific archetypes.

CLDs can uncover hidden relationships, enabling me to develop dynamic hypotheses about the interactions within systems. This structured approach helped me uncover interconnections within the system and break down the complexities of longevity planning services.

The power of CLDs lies in their ability to identify underlying needs and motivations. They help answer critical questions, such as: What drives individuals to make decisions? What common themes might have been overlooked during the interviews? What might participants be hesitant to share?

These insights from extreme user interviews are invaluable for helping designers and researchers synthesize findings and translate them into actionable insights.

Designing for extremes can inspire innovative approaches to address challenging conditions, such as severe weather or diverse demographics.

Professor Dava J. Newman, Director of the MIT Media Lab, has pioneered the development of a functional, flexible, and adaptive space suit designed to function as a “second skin,” enabling a visionary outer space travel experience (Figure 3).

In 2022, Newman led a collaborative effort at the MIT Media Lab alongside the Architecture Self-Assembly Lab, the AeroAstro Human Systems Lab, and the ME Multifunctional Metamaterials Group to present the 3D Knit BioSuit™—a groundbreaking multidisciplinary research and design project.

This project explores how emerging technologies, such as advanced material science and smart fabrics, can be applied in extreme environments, like outer space, to help astronauts or potential space travelers perform their tasks with greater efficiency and effectiveness.

It also offers valuable opportunities for research and problem-solving, such as exploring the application of smart fabrics in other domains like children’s clothing design and materials, including disposable diapers, with the aim of enhancing breathability and adaptability to various body types.

Similarly, MIT’s work on innovative wearables extends to addressing challenges for aging population (Figure 4). In 2005, MIT AgeLab developed AGNES 1.0 (Age Gain Now Empathy System), an empathy suit designed to simulate the physical challenges associated with aging.

AGNES replicates age-related conditions such as muscle loss, reduced mobility, diminished flexibility, and impaired sensory perception. Features include foam inserts of varying heights on the soles to simulate balance issues and goggles with specific surface treatments to mimic visual impairments.

AGNES has been instrumental in projects such as redesigning the CVS retail environment through the lens of “extreme demographics.” This redesign focused on optimizing store layout, wayfinding, and furniture to better serve older adults. For example, the team reimagined shelf heights for frequently purchased items and strategically positioned popular products to improve accessibility for seniors.

Beyond retail, AGNES has been employed in diverse settings, including public transportation and workplaces, helping designers, engineers, and policymakers create products and services that are more inclusive and accessible to older adults.

Both the 3D Knit BioSuit™ and AGNES exemplify the exploration of user needs in extreme contexts—whether in the demanding environment of space travel or in simulations designed for extreme user groups, such as the aging population. The concept and experimentation with “extremes” have sparked creativity and curiosity by challenging assumptions about everyday experiences. Ordinary senses and abilities, such as gravity and mobility, are reimagined, disrupted, and transformed, leading to innovative solutions and fresh perspectives.

Extreme behaviors or personas can redefine norms, fostering greater innovation and expanding possibilities.

Naturally, it enables me to think of the era of COVID-19 since 2019. Most of us have experienced “survival” in this extreme environment. We quarantined in our home with limited commuting and traveling.

Even now, in the post-COVID era, many new norms have emerged. For example, most companies and research institutes have created new policies around working from home with more flexibility and space to deliver contributions during the weekdays. The common use of Zoom and other virtual meeting software has risen to cultivate a novel working and relationship-building culture.

Everything, like a double-edged sword, has advantages and disadvantages. I see more adaptability for designers who freelance. After the pandemic, IDEO reconstructed the organizational structure and business model to create a cloud-based design team. The organization can assign different projects to creative teams around the globe, somehow lowering the geographic barriers to work. The business strategy from location-based constrains to cloud-based capabilities.

Meanwhile, organizational culture has been transformed. How do we cultivate a creative culture if everyone is virtually present? Can we still have real collaborations and field trips, or can we simply invite participants to move virtual Post-its notes around on the Miro board in what we call co-creation workshop? These are the concerns that I believe could potentially have adverse effects.

I don’t have definitive answers yet. However, I firmly believe that creativity must and will thrive under extreme conditions, behaviors, and interactions—such as those experienced during COVID-19—driving adaptation and evolution. This aligns with the phenomena shaping our aging society.

In today’s era of a super-aging society, people are living longer while striving for an improved quality of life. This demographic transformation presents a more “extreme” condition, requiring significant adaptations. Countries worldwide face major challenges in preparing their health and social systems to meet the needs of this demographic shift effectively.

Between 2015 and 2050, the proportion of the global population aged 60 and older is projected to nearly double, rising from 12% to 22%. Moreover, the percentage of the aging population is increasing at an accelerating pace, surpassing previous rates.

Our social infrastructure, including financial planning, healthcare system, educational platform, governmental policies, investment environment, and other visible and invisible factors, has enabled us to innovate to reenvision potential solutions under these extreme conditions.

What we learn from extreme users can help redefine design norms, rituals, and maybe even our culture and directly or indirectly influence our everyday lives. Be empathetic and human-centered and consider how you incorporate insights gained from extreme users and challenging environments into your work and daily life within your specific context.

Reference:

- Dava J. Newman

- Dava Newman presents 3D Knit BioSuit™ at 2022 MARS conference

- Unique MIT suit helps people better understand the aging experience

- Play Seriously

- Teague