Rethinking mobility to design better cities with Max Schwitalla

Founder of Studio Schwitalla, Max Schwitalla shifts the urban planning paradigm and explores how new forms of urban mobility enable the design of future cities.

As architect and founder of Studio Schwitalla, Max Schwitalla is shifting the paradigm of urbanism and advocates the reevaluation of urban planning and architecture to create infrastructures that serve as a means of enhancing mobility in societies while building cities that make us healthy and happy.

The ability to move around a city is a basic need for the growth of most human activities. As cities are constantly evolving and changing, urban planners and designers need to think ahead and truly envision what the future of mobility should be when creating future infrastructures. While providing smart mobility solutions is a stepping stone for a better tomorrow, it is becoming more clear mobility is the end, infrastructure the means, and people should be at the center of it all.

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

It is evident urban planning and mobility go hand in hand, and while there are many designers focusing on each field individually, there is one that focuses on the intersection of both and brings back people at the center of every design, Max Schwitalla. It is through the experimental work of Studio Schwitalla that Max focuses on neighborhoods as three-dimensional structures, the future of urban mobility and the re-negotiation of spaces to generate transformable urban environments centered on human needs.

In a pursuit to understand how urban mobility becomes an integrated part of our city development, DesignWanted interviewed Max Schwitalla and learned more about Studio Schwitalla’s research, design focus, and how to design a hyper-connected city with transformable and sustainable urban environments centered on human needs.

Who is Max Schwitalla? How did the journey for architecture, urban mobility, and urban design begin?

Max Schwitalla:

“I am an architect and urban designer with a passion for urban mobility. I grew up in southern Germany and after living abroad for some time, I am based in Berlin since 12 years.

I fell in love with buildings and cities through skateboarding as a teenager – on the move through the city. Therefore, I decided to study architecture in Stuttgart and at the ETH Zurich and I was fascinated by the synergetic potential of the mobile and the immobile realm from the very beginning until today, 40 years old.”

What moved you to start Studio Schwitalla? Why focusing on the intersection of Architecture, Urban Mobility, and Urban Design?

Max Schwitalla:

“After working in big offices like OMA or HENN also on big urban development projects in China among others, I decided in 2012, that I want to focus again on this old passion, the intersection of the urban mobility sector and the immobile urban environment.

If we consider that the construction and operation of buildings as well as the transport of people and goods sum up to around 60% of all global CO2 emissions, it seems obvious that we can achieve a lot, if we think more integrative here!

So, I was literally ‘moved’ out of personal passion and objective necessity to start a studio with the research and design focus on how future urban mobility will shape the urban environment differently and we found research partners from the mobility industry, like Schindler Elevators, who wanted to collaborate with us.

That’s how the journey of my studio started with the goal to develop design proposals for neighborhoods and urban spaces, that are much more human centered, less car dominated and with a human-scale density.

Because in our view, there are two extremes how mobility shapes the urban environment today: one is the car city – Los Angeles for example – characterized by low-density horizontal sprawl, massive CO2 emissions and economic damage through time wasted in traffic jams. The other extreme is the elevator core city – New York City for example – a vertical city that is reaching the limits of social sustainability because we add more and more private space to the city, stacked in towers, but we don’t add enough public space where people can actually meet and exchange.

This leads to an imbalance between increasing private and the, in relative terms, decreasing amount of public space.

These urban typologies of the 20th century have clearly reached the limits of sustainability and we really have to ask ourselves: why do we still build cities for cars and elevators that actually separate people from each other, in SUVs or stacked in towers?

But when we stop owning cars, which we have to utilize every day, we can think about the urban environment in new ways literally: instead of a linear urban growth along streets (or vertical dead ends for the elevator) we should conceive the urban environment as an organism of hyperconnected neighborhoods, with a powerful public transport network and shared micro-mobility for the short-range distance within mixed-use neighborhoods.”

Studio Schwitalla aims for future cities as places with high quality of life, how do small scale and electric micro-mobility will enable this?

Max Schwitalla:

“We need to build cities that make us healthy and happy! Various studies show clearly the correlation of the percentage of the population with obesity and the modal share of active mobility in different countries: more car usage, more obesity – more walking and cycling, less obesity.

Active mobility makes us healthier and therefore happier and especially now, during the Covid-19 pandemic, many cities installed new bike lanes to make more space for cyclist because people also avoid public transport at the moment. And as urbanization and densification is constantly increasing, we believe the revolution comes from below: small, silent, shared vehicles – that might be autonomous so they don’t have to be parked – allow us to rethink neighborhood typologies.

Instead of driving with a car into the underground parking and then taking the elevator to the apartment, the electrification of micro mobility allows for truly three-dimensional circulation networks including the horizontal, the vertical and the diagonal dimension. E-bikes, for example, make it possible to travel faster, but more interesting is that they enable people of every age to comfortably overcome height differences.”

Human-scale mobility technologies and the corresponding geometric parameters of flow (e.g. radius of curvature or ramp inclination) lead to different spatial implications and to novel urban morphologies.

A neighborhood can now be designed as a hilly and diverse landscape of stacked platforms: like a mountain range eroded by the flow of people, with ascending and descending cycle paths and terraced public spaces. A series of double height platforms, connected via ramps, serve as the “Urban Shelf”, a load-bearing megastructure providing floor, ceiling and technical infrastructure.

This open structure can accommodate change between the platforms, making it adaptable and therefore sustainable while also allowing user participation or even do-it-yourself construction. Two-storey maisonettes or townhouses between the platforms with a front garden for parking small vehicles (e.g. e-bikes) would provide sufficient privacy for residents within the public megastructure.

Ideas for megastructures or flexible infills have been around also in the 1950s and 60s, for example Constants “New Babylon” or Yona Friedmans “Ville Spatiale” – but it is only now, in the context of such dramatic urbanization, that the necessity to design dense but human-scale, adaptable and sustainable urban spaces has become so urgent.

And the technologies are only now at hand to allow such utopian concepts turn into reality and to help finding answers to the pressing challenges of future urban development. Alongside modular and digital construction methods, new materials or innovative fire protection concepts, we believe mobility technologies allow us to find new ways for human-centered urban design.”

In a future where the mobility system is based on a sharing economy, what would be the role of mobility hubs in the future? How would that shape neighborhood interaction?

Max Schwitalla:

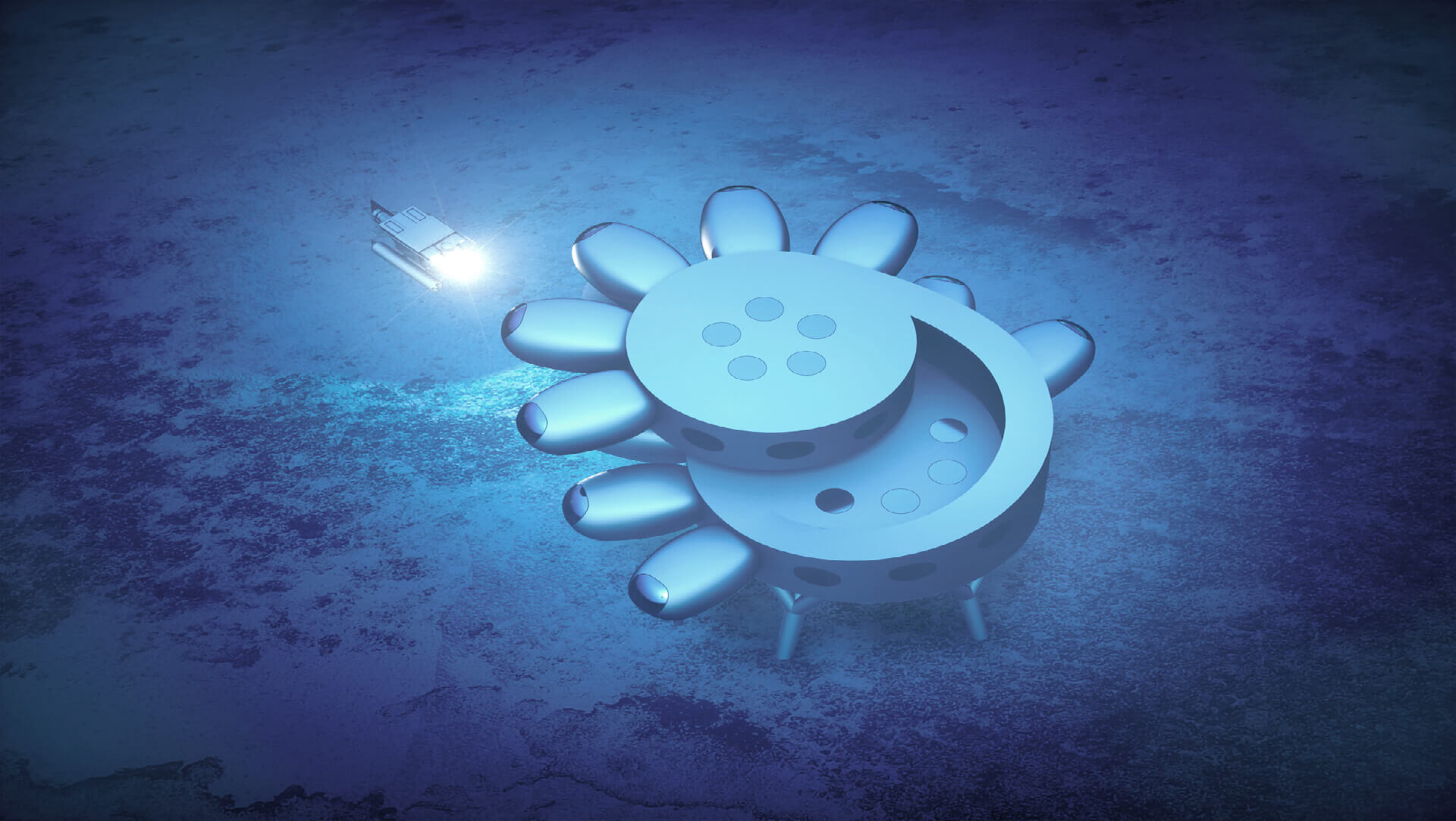

“The Mobility Hubs is a new urban typology located at the different intersections of intermodal mobility chains (for people and goods) that include for example a subway and shared mobility for the first and last mile.

The structure organizes functionally and connects spatially the different scales of transport from rapid/transfer to slower/local connections. Here is where you can also leave your private or shared car and hop on a shared e-bike for example. But it’s not only a place to change transportation methods, it is a place where we can change the way we think about urban mobility and it’s a place to exchange with the people in your neighborhood.

It’s an infrastructure for social exchange that includes different services and functions for the community like a grocery store or a kindergarten. The Mobility Hub works like a catalyst in a traditional neighborhood because we have less cars on the streets. These can be reprogrammed temporarily and turn into multifunctional spaces for various community activities. We could even think of different materials other then the traditional concrete, that are more enjoyable to walk on.”

The “Tübinger Regal” refugee housing project implements some ideas of your “urban shelf” concept on a building scale, could you tell us more about the mobility concept for this building and how it could be developed further in new projects?

Max Schwitalla:

“Because we developed a mobility concept that includes a shared car on site among other things, we were able to reduce the number of parking spaces required according to the regulations and like this we could eventually gain more usable space for the people who live here.

And in the same way that mobility is inspiring our designs on an urban or neighborhood scale, like the Urban Shelf, the circulation within a building is the driving design concept on an architectural scale.

In this case we implemented external open balcony access in combination with multiple open staircases connecting the four floors. Each unit has a slightly tilted façade which opens up little pockets and in contrary to a straight corridor, these pockets articulate each unit on the floor and give identity.

Within the pockets we built some seating possibilities, made from the same recycled bricks that we used in the façade due to fire regulations. The circulation area is facing south and has a beautiful view over the landscape, it really works as an integrative communal space that fosters communication and social interaction between the refugees from very diverse backgrounds as well as the students, who also live here in microapartments.

We will definitely work again with variations of open balcony access circulations in the future, maybe more terraced or in combination with double height units, as proposed in the Urban Shelf. Another idea from the Urban Shelf was to implement a skeleton structure with barely any load bearing walls – like this the units could later be combined or subdivided, if ever needed. We used as little concrete as possible and the two-layered façade is made out of wood and recycled bricks, as we wanted to build affordable and ecological.”

Studio Schwitalla usually contributes to visions about mobility, exploring mobile society through visual art. What are the main trends & future directions within urban mobility design and what do you think of them?

Max Schwitalla:

“As described before, we believe the mobility revolution comes shared and in small scale with micromobility. We are still in the first experimentation phase with new trends like e-scooters and we should not judge too quickly and complain about a scooter on the sidewalk next to tons of parked steel blocking our streets since decades.

These shared models also lead to shared responsibility, for example, if normal citizens can earn money by picking them up to charge at home in the evening and placing them back on the streets the next morning. Huge, powerful and self-driving cars with enormous batteries won’t be the solution for urban mobility, especially if they are still privately owned – but self-driving people mover as part of a free public transport network or robots that carry your shopping bags home and then return to the grocery store to help the next customer will do!

I also believe last-mile solutions for people and goods as well as indoor mobility solutions (including vertically) will become more and more important and I am looking forward to the next generation of three-wheeled or partially covered e-scooters.

I am very skeptical about passenger drones as individual traffic above our heads because the sky will be black soon and the noise pollution extreme, but I think a flying bus would be fantastic, serving direct point to point connections between different neighborhoods. Next to Mobility Hubs we need to keep improving the infrastructure for micromobility and I am happy to see that the political will becomes stronger all over the world to finally reallocate existing infrastructure fairly in favor of active mobility.”

Focusing on a symbiotic fusion between urbanization, mobility, and digitalization. What are the future plans for Studio Schwitalla?

Max Schwitalla:

“As we find inspiration in the mobile realm to design immobile spaces, we consequently explore new ways of architectural communication and storytelling through motion picture.

Our media department, lead by creative director Sergey Prokofyev, creates advanced immersive experiences from AR and VR to dome projections, for example in Schindlers Port Innovation Lab or as part of an academic cooperation with neuroscientists.

We aim to realize more architectural projects designed around circulation, like a proposal to cover Berlin’s exposed firewalls with a thin slab, cut diagonal by an open stairway and we are very excited to participate in a federal research project to develop prototypes for Mobility Hubs in Hamburg.

And behind the Mobility Hub unfolds a whole world of design possibilities for new neighborhoods, that just wait to be realized somewhere :)”