How urban design changed Russia’s monotown image – A talk with DROM Architects

During the 2000s’, according to the Russian Government, there were 467 cities and 332 towns classified as monotowns

Monotown refers to a city entirely dependent on a single industry dominance. Naberezhnye Chelny is one of the biggest monotowns where Azatlyk Square’s eminent urban design took place by DROM Architects.

During the 2000s’, according to the Russian Government, there were 467 cities and 332 towns classified as monotowns. As of 2018, there are 391 monotowns currently active along with opportunistic areas for ambitious urban designs in Russia including Naberezhnye Chelny, a Soviet city built in the 1970s’.

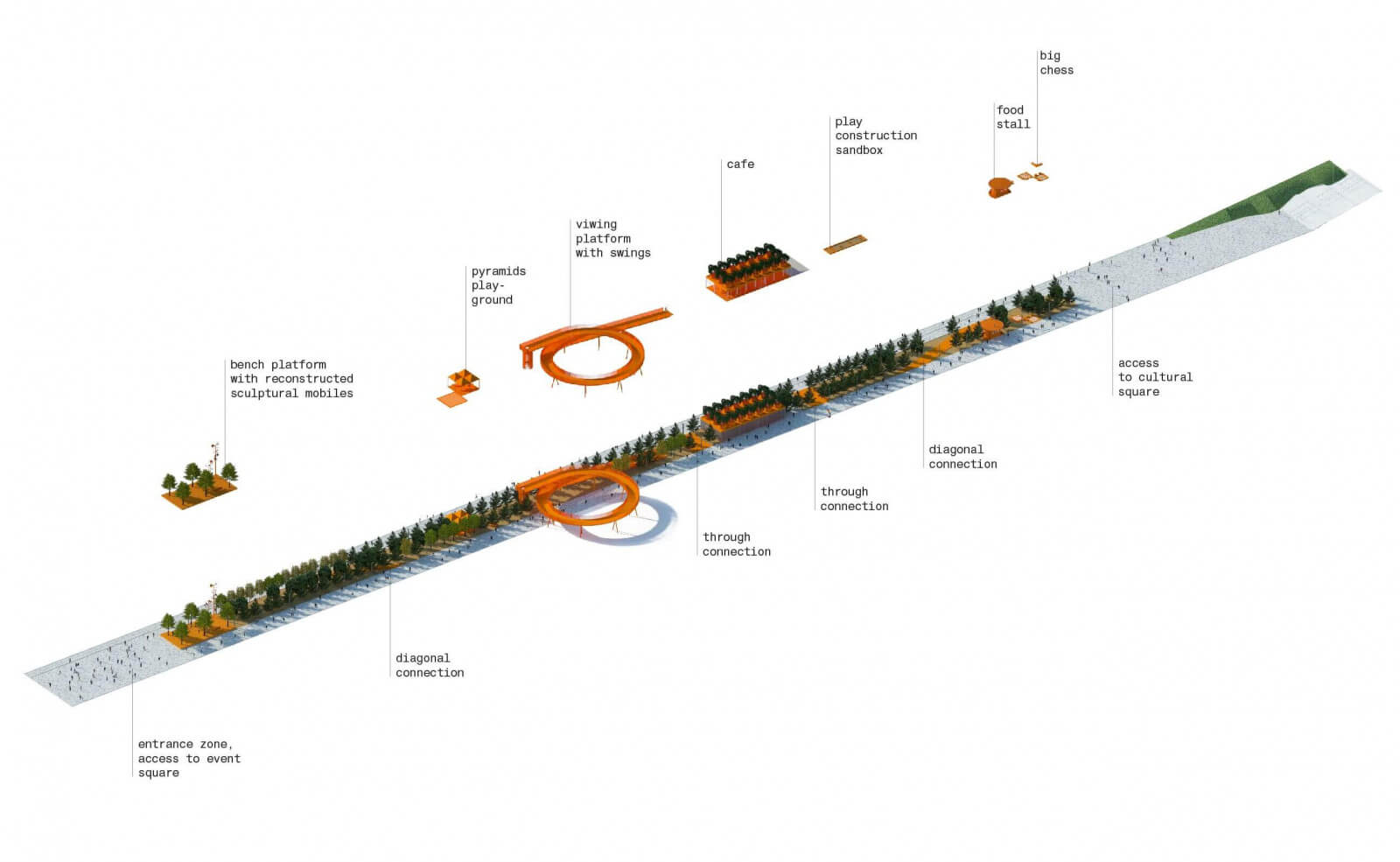

Azatlyk Square is the central square, originally planned on a central axis to connect two distinct landmarks; the municipality building and the Lenin museum. Although, the museum never got built and the axis lost its meaning. Resulting in a space left as an underused memento, disconnected to the city.

The renovation of the square is a joint attempt towards improving life in Russian cities by DROM, Strelka KB, DOM.RF and KMT Pro and the mono-city development fund. DesignWanted had the chance to interview the team of DROM Architects to learn more about their work and the hurdles in forming a new identity of a city.

How did the firm DROM start? What is the vision of DROM?

DROM Architects:

“DROM started by winning an invited competition for three residential towers in Siberia, in Novosibirsk. At that time, we still worked for different companies and were looking for possibilities to start on our own. We didn’t begin with a clear vision but with just a desire to work independently.

Over time we started to better understand our values and capabilities. We realized that independently from any fascinations we have in certain periods of time the key for our design is brining together different scales – urban, architectural, interior – into coherent overarching proposals that are built.”

What is your general approach in designing public spaces?

DROM Architects:

“Independently from scale or type of project we always approach it as part of a bigger system and a system on its own. We try to understand the ideological underpinning and essence of a place, analyze the greater physical context and the role that our potential intervention can have on an area. Then we always question the brief and try to work together with our clients to make it clearer and more intentional if necessary. We find that there are always things that a client may have not considered for different reasons.

During our internal brainstorms, we always try to find some sort of a hidden “tension” inherent in a place, to understand what it wants to become and how to make this transformation happen with just a few simple and clear gestures. For example, in the Azatlyk Square project, this tension moment was the position of the main circulation axis. Initially, it was placed in the middle of the square, loaded with ideological baggage and rarely used by people – it was connecting the city hall building with the museum of Lenin, which was never built.

We moved this axis to the edge of the square, where people could be protected from the sun and wind by already existing lines of trees. Instead of organizing central perspectives towards the symbols of power it became tangent to the surrounding functions and open to be extended and complemented in the future.”

What was the greatest struggle through the entire design process of Azatlyk Square, in terms of planning, managing timeline and building it in reality?

DROM Architects:

“The timeline for the initial concept phase was very short and the project was very ambitious. We started with a concept at the beginning of the year and broke ground already by summer. There were times during the construction that we thought we could lose critical aspects of the project, by materials being replaced from what we specified, or details being changed.

Our collaborators, Strelka KB and local architects KMT.pro were key to achieving the quality of construction and our ability to maintain the integrity of the design. We still remember how much anxiety we went through, when we were choosing materials and colors – we had just a few hours, while our local partners were at the concrete factory. They were checking the available colors and putting together mock-ups in real-time.

We were stirring this process on-line from Rotterdam, testing color combinations and patterns. Of course, there were also other anecdotes connected with the project, for example, a crate of cognac, which our local architects bought and used to motivate the construction workers to follow the alignments. As a result, we feel that we were able to achieve quite an impressive precision and quality of execution for the local context.”

What were the major constraints for renovating a vast area of 7.8 hectares of Azatlyk square?

DROM Architects:

“The enormous size of the site, its monotony and emptiness were, of course, posing serious challenges but at the same time, this was giving us a lot of freedom to operate in a very creative way. There was enough space to create different character areas – we basically made three squares – each with its own atmosphere and which is tailored to different activities.

Obviously, there were financial constraints – any material you specify is multiplied by the number of square meters, which here was huge. We did not use almost any natural stone, except a bit for the fountain.

Also, street furniture and equipment were produced locally with available technologies. So, we intentionally designed them in simplified geometries and using standard industrial elements. For example, the shape of the spiral viewing platform was only possible to achieve with the bent pipes, which are normally used in the Gazprom pipelines.”

Considering Naberezhnye Chelny is a monotown, how did you connect the renovation of the area with the historical context and the people living there?

DROM Architects:

“Naberezhnye Chelny is not just a regular Russian monotown. Back in the seventies, the city was an experimental ground for planners, architects, and designers, who came here from all over the country. Of course, most of their visions remained on paper. And the city, which appeared so quickly is hard to call appealing but is bold and impressive in the scale of its open spaces.

In our design for the square, we were trying to work with this inherent spirit of experimentation and courage. We were participating in a series of workshops with the local architectural community, where they shared their ideas and thoughts about the square. Some of them we implemented in the final design.

Also, in the details, we were trying to build a link with the city’s context. KAMAZ truck factory is the economic backbone of the city. And we used the colors of the first KAMAZ truck cabs – orange, blue, red – for the structures and objects, which we placed on the square.”

What is the timeline for the completion of all 3 phases?

DROM Architects:

“Construction of the first phase was completed roughly in the winter of 2018. The second phase was completed in the fall of 2019 and the third and final phase of the project is expected to be completed in the summer of 2020.”

What are the major issues related to operating on such large-scale projects in a different country from yours?

DROM Architects:

“The main challenge is maintaining the integrity of the design and quality of construction while not being physically present.”

Since your firm operates worldwide, what would be your aspired project if you got a chance to create something without any constraints?

DROM Architects:

“We think that projects without constraints don’t exist. And even if we get this impossible commission, we would try to invent some constraints by ourselves. Since our firm is based in Rotterdam, we would like to get a project here and try our hand at furniture.”