From fast food to fine dining: what kind of design education are we cooking?

In an era of AI, the question is no longer how fast designers can work, but what kind of design education we are cooking.

Just before the Christmas holidays, I found a rare moment to pause and reflect while waiting to board a flight—an in-between space after the intensity of a demanding final semester at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

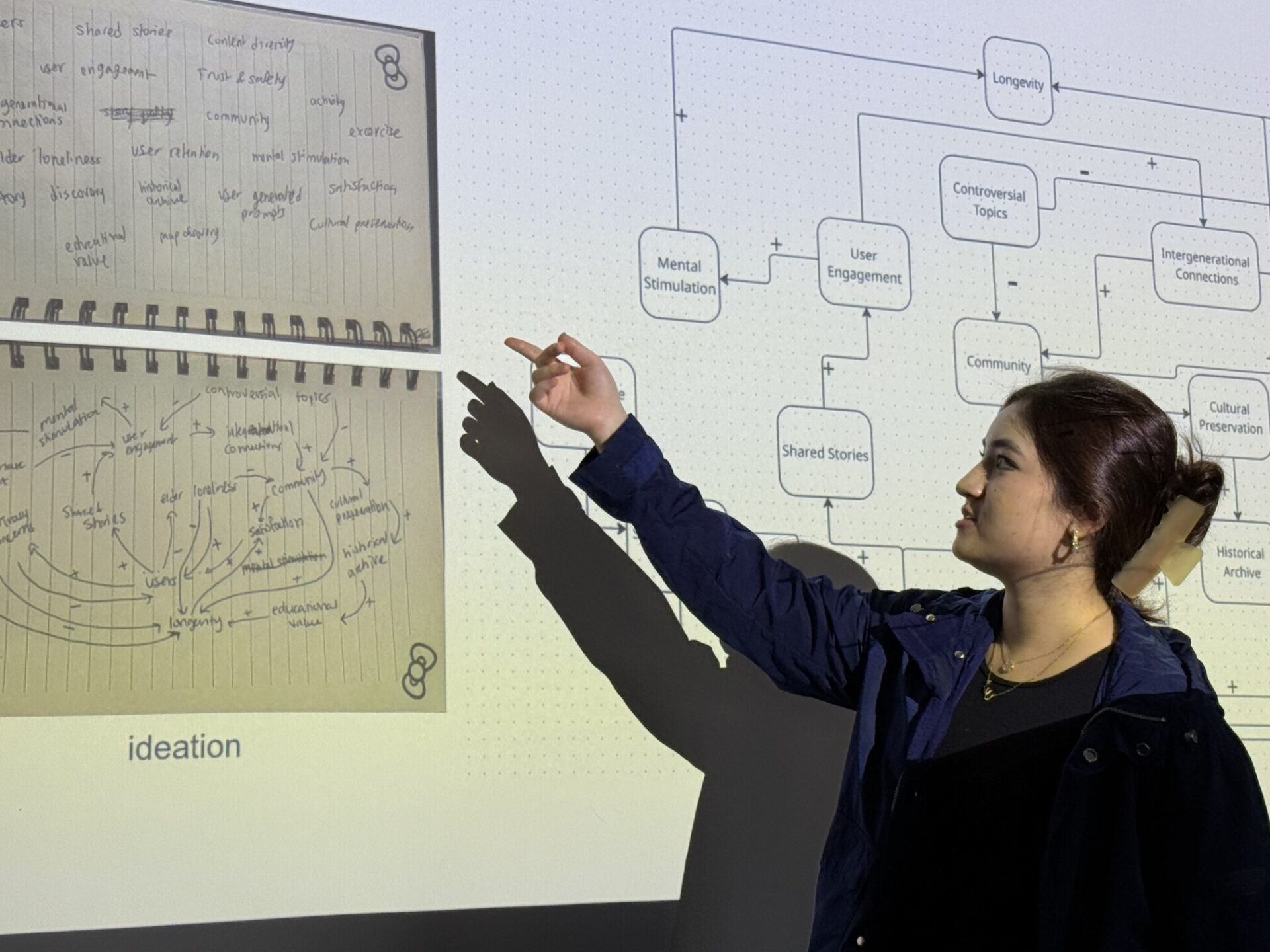

Over the past two months, my teaching and academic engagements spanned multiple institutions and pedagogical contexts. I lectured in an undergraduate course on Interaction Design Principles at Northeastern University’s College of Arts, Media and Design (CAMD) (Figure 1), facilitated a three-hour participatory workshop at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt) and Dubai Design Week, and also served as an External Critic for the Industrial Design graduate program at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign (UIUC).

Moving across these classrooms, studios, and critique spaces offered more than moments of instruction and dialogue. Collectively, they created a vantage point from which to reflect on a larger, pressing question: what kind of design education are we preparing for the future, especially in an era increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence (AI)?

When we rethink what design education serves today, are we lining up for fast food or making a reservation for fine dining? What do we expect from the next generation of designers?

McDonald’s represents standardization, scalability, feasibility, adaptability, and accessibility. It is efficient, predictable, and optimized for speed. A Michelin-star restaurant, by contrast, stands for storytelling, craftsmanship, sophistication, scarcity, and experience. It is slow, intentional, and deeply contextual.

Neither model is inherently good or bad, but the distinction reveals a tension at the heart of contemporary design education. In a moment when AI can rapidly generate concepts, images, and solutions, efficiency is no longer the primary challenge. Meaning, judgment, and responsibility are.

In this reflection, I outline three interconnected perspectives that point toward alternative ways of teaching design:

Design Education – Three interconnected perspectives:

Together, these three perspectives suggest how design education might move beyond speed and scale—toward depth, interpretation, and long-term impact—better equipping designers to navigate complexity, uncertainty, and their evolving role in the age of AI.

Perspectives 1. Reframing the mindset from “learning” to “unlearning”

Much of the current discourse across articles, research, and case studies focuses on what AI can do for designers. Integrated into conventional design processes, generative AI enables designers and students to rapidly produce ideas, concepts, and visualizations.

Tools now span text-to-image generation (e.g., Midjourney, DALL·E, Stable Diffusion), writing support (e.g., ChatGPT, Jasper), UI/UX design (e.g., Uizard, Figma AI), and marketing graphics (e.g., Microsoft Designer, Canva), accelerating ideation, improving efficiency, and transforming simple prompts into complex design outputs.

Prompt-based interfaces, in particular, have dramatically lowered the learning curve of design work, especially in stages such as ideation, CAD modeling, and rendering.

With the rise of generative AI tools, our understanding of what it means to “learn” design has fundamentally shifted. The time and effort traditionally required to train designers or students to master software, tools, and technical skills has been significantly reduced.

As a result, design capabilities have become more accessible, scalable, and widely distributed. However, the more critical question is no longer what designers need to learn, but what they need to unlearn.

Unlearning, in this context, does not imply discarding knowledge. Rather, it introduces flexibility and resilience by prompting a re-examination of which forms of knowledge truly matter for designers, for design education, and for the design process itself.

Historically, designers were expected to memorize professional terminology, master specific software, and adhere to rigid manufacturing protocols. A mindset of unlearning shifts the emphasis away from accumulation and toward internalization.

A notion of unlearning asks designers to deepen their lived experiences, critically reflect on what they have already learned, and translate that knowledge into insights that can be meaningfully articulated and shared in more accessible ways.

Unlearning does not impose a higher cognitive burden than learning. On the contrary, it redirects designers’ expertise toward curating human-centered experiences rather than merely producing physical artifacts.

Unlearning is not a loss of expertise; it is a reorientation of expertise toward judgment, interpretation, and sense-making within an AI-augmented design landscape.

>> Reflection 1. Unlearning is less about adding ingredients, and more about rethinking the recipe.

Perspectives 2. Extending Human-Centered Design (HCD) toward HCD+

Human-Centered Design (HCD) has long served as a powerful and necessary foundation for addressing design challenges. It remains a dominant norm across design education and practice, offering structured ways to understand users, articulate needs, and translate insights into solutions.

Yet, despite its strengths, HCD also reveals important constraints, particularly when we consider how design processes and outcomes scale, and what kinds of futures they ultimately support.

In Don Norman recent book Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity-Centered (2023), he articulates a pivotal shift from Human-Centered Design (HCD) toward what he calls Humanity-Centered Design, or HCD+.

Through five guiding principles and a series of case studies, Norman reframes design not merely as a response to individual user needs, but as a responsibility to broader social, ecological, and systemic contexts.

Historically, our understanding of HCD emerged in the 1980s, closely aligned with the rise of industrialization and mass production. Designers were expected to create tailored solutions for users while optimizing standardized processes: balancing human factors, manufacturing costs, marketing demands, business value, distribution strategies, and short-term outcomes (Norman, 2023, pp. 17, 84). Within this paradigm, success was often measured by efficiency, usability, and market viability.

HCD+, by contrast, expands the scope of care. It asks designers to consider not only people, but all living beings and the interconnected systems that sustain them. While short-term results and industrial constraints still matter, the emphasis shifts toward long-term goals, life-centered values, and positive societal impact (Norman, 2023, pp. 83, 183, 299). Design, in this sense, becomes a form of stewardship concerned with sustainability, ethics, and collective well-being.

HCD+ is inherently more inclusive and adaptive. At times, it even requires designers to move beyond strictly human perspectives. Can we extend empathy to non-human actors: animals, ecosystems, or future generations (Figure 2)?

Emerging areas such as animal-centered design and more-than-human design illustrate how expanding our ethical and conceptual boundaries can reshape what we consider “good” design.

This expansion also raises critical questions for design education. If HCD has been teachable, transferable, and assessable through established pedagogical frameworks, can HCD+ be taught in similar ways?

Do our current evaluation criteria meaningfully capture long-term impact, systemic responsibility, and more-than-human considerations? And what new forms of design expertise, such as ethical reasoning, systems thinking, and ecological literacy, must be cultivated to meet the standards of HCD+?

These questions suggest that extending HCD to HCD+ is not merely a theoretical shift, but a pedagogical challenge, one that demands rethinking how we teach, evaluate, and ultimately define design in an era shaped by AI, complexity, and planetary urgency.

>> Reflection 2. HCD+ asks whether we are designing for diners alone or for the entire ecosystem behind the kitchen.

Perspectives 3. Shifting from “DESIGN” as a discipline to “design” as a situated, everyday practice

Uppercase “DESIGN” refers to approaches that are explicit, visible, and often loud, processes that prioritize clarity, speed, and predictability. In contrast, lowercase “design” represents what is subtle, implicit, and unpredictable. These two typographic metaphors signal different pedagogical perspectives on how we approach design education today.

When we speak of DESIGN, we can rely on tools such as mind maps or ideation frameworks to quickly visualize, externalize, and tangibilize ideas. These methods are effective for organizing thoughts, generating options, and communicating concepts efficiently.

By contrast, design is less about listing elements and more about questioning relationships. It encourages curiosity about how elements interact, influence one another, and evolve over time. In this mode, designers, researchers, and educators move beyond representation toward interpretation and sense-making.

Methods such as Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs) stemming from the field of system dynamics become particularly valuable in this context. CLDs allow designers to investigate hidden dynamics and systemic relationships among stakeholders, elements, and components, revealing underlying patterns and shared, often unarticulated, human needs. Through this lens, design shifts from producing artifacts to understanding systems, interdependencies, and long-term implications (Figure 3).

Lowercase design resonates with several complementary ideas, including Slow Data, Future Mundane, and Slow Looking. Anthony M. Townsend’s notion of Slow Data (2013) emphasizes using data not merely for optimization, but to drive deeper behavioral and social change.

When thoughtfully paired with big data, slow data offers a counterbalance: where big data enhances efficiency, slow data invites reflection on social trade-offs and ethical consequences embedded in everyday life.

Nick Foster’s concept of Future Mundane (2025) similarly reframes the future as an ordinary place—one shaped not by spectacle or prediction, but by attentive, critical, and imaginative engagement with the present. The future, in this view, emerges through grounded inquiry rather than grand forecasts.

Shari Tishman’s idea of Slow Looking (2018) further reinforces this perspective. Slow looking is a mode of learning rooted in prolonged, attentive observation. It resembles the patience of a wildlife photographer waiting to capture subtle behavioral shifts, or the quiet immersion of birdwatching in one’s backyard.

Such practices require time, lingering, and attunement, as their aim is to perceive nuance, relationships, and implicit patterns. As a pedagogical stance, slow looking offers a crucial counterbalance to our natural tendency toward speed, immediacy, and surface-level perception (Figure 4).

>> Reflection 3. DESIGN vs. design: Michelin-level design is not louder; it is quieter, slower, and more deliberate.

Conclusion: Designing education beyond speed and scale

This perspective article argues that design education is at a crossroads. In an era where AI can accelerate ideation, visualization, and production, the central challenge is no longer efficiency but meaning.

The metaphor of McDonald’s versus Michelin reveals a deeper tension between scalable, standardized “DESIGN” and slow, situated “design”—between speed and judgment, output and responsibility. Three reflections emerge:

- Reflection 1. Unlearning is less about adding ingredients, and more about rethinking the recipe.

- Reflection 2. HCD+ asks whether we are designing for diners alone or for the entire ecosystem behind the kitchen.

- Reflection 3. DESIGN vs. design: Michelin-level design is not louder; it is quieter, slower, and more deliberate.

By reframing learning as unlearning, extending Human-Centered Design (HCD) toward HCD+, and shifting from “DESIGN” as a discipline to “design” as an everyday, relational practice, the article calls for a recalibration of what we value in design education.

Rather than training designers to produce faster, more predictable outcomes, the future of design education lies in cultivating interpretation, ethical sensitivity, systems thinking, and long-term imagination.

The future of design education may not lie in choosing between McDonald’s or Michelin, but in deciding when speed serves us, and when slowness is essential. In this sense, the goal is not to reject speed or technology, but to ensure that, in the age of AI, design education continues to nourish depth, care, and lasting positive social impact.

Reference: