Design for Vulnerability (D4V): Adaptability, Artifacts, and Apprehension

As design researchers engaged in the creative industry, how can we enhance our readiness regarding attitude and skills to foster effective collaboration and co-creation with vulnerable communities?

During this winter break, I had the honor of partnering with the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME) Social Design Hub to kickstart this initial research project. The endeavor is sponsored by the Foundation for Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design’s Global Voices initiative and enjoys the support of the university’s Innovation Center. The project was carried out under the umbrella of the Social Design Hub.

The purpose was to explore how we can empower teenagers from lower socioeconomic backgrounds or disadvantaged groups through design and making to comprehend how the vulnerable communities project their future selves and perceive problem-solving on both individual and societal levels.

This collaborative effort aimed to integrate the Design for Longevity (D4L) project with FRUSKA, a research initiative and design workshop catering to disadvantaged girls’ communities. The FRUSKA project is led by Janka Csernák, a social design researcher affiliated with the MOME Innovation Center (Figure 1).

This ongoing project is currently at an early stage of research, with a significant portion dedicated to on-site studies. This involves a four-week fieldwork investigation conducted at the Belvárosi Tanoda Foundation Secondary School: The Helping School in Budapest (Figure 2).

Throughout this phase, I immersed myself in the research alongside Csernák Janka. Together, we identified and clarified potential research questions as the project unfolded.

Design for Vulnerability: Adapatability, Artifacts, and Apprehension

Design for Vulnerability (D4V)

Having spent one year working as a prison guard in Taiwan, I find a particular resonance with the challenges of engaging with vulnerable communities.

I consider myself fortunate, sharing the common privileges of a stable income, a normal and lovely family, middle-class social status, and good physical health. As a researcher in this project, I explore how to effectively study and work with vulnerable communities.

From my understanding, the concept of Design for Vulnerability (D4V) revolves around designing for these marginalized communities, encompassing individuals or families from lower socioeconomic backgrounds within underprivileged communities.

The Living Museum

Various design projects or design research categories focus on vulnerable communities, such as design for social justice, design for social impact, or design for addressing gender bias. For example, The Living Museum located in Queens, New York, aims to establish arts and design communities with a sustainable business model and health systems to serve as a therapeutic outlet for patients, unlocking their creative potential (Figure 3).

Bolek Greczynski, Co-founder of The Living Museum, mentioned the essence with this power slogan, “Let your vulnerability be your weapon.“

Threads of Assumption

Another example, the Threads of Assumption project in Boston, aims to delve into sensitive and vulnerable topics surrounding gender bias, artificial intelligence (AI), culture, and identity through the application of weaving and participatory workshops.

The project, led by four artists from diverse backgrounds – a composer, an educator, a poet, and a multimedia designer – involves the collection of personal stories through workshops and surveys, specifically focusing on gender-based harm. These narratives were then analyzed to identify patterns in the data.

The synthesized data and personal stories were transformed into an impactful and immersive experience through multimedia, incorporating elements such as musical performance, digital visualizations, weaving arts, and live poetry.

Design research ethics

Conducting thoughtful on-site ethnography research poses numerous challenges. In addition to basic considerations such as funding, resources, time, connections, and the research team composition, the soft side of design factors like language barriers, cultural differences, work styles, weather conditions, mental stress, and other personal and professional considerations impact the project.

Jane Fulton Suri, IDEO Partner Emerita, captures the essence of ethical design research: “Ethical design research is about the quality of relationships. Our goal is to manifest trust in individuals; to build communities of trust; to form trusting relationships with the people we’re designing for and alongside.”

IDEO, a global design and innovation company, unveiled the second edition of The Little Book of Design Research Ethics last year, featuring six principles with illustrative examples: respect, responsibility, honesty, inclusion, and evolution.

While these principles provide a solid foundation as a starting point, their significance becomes even more pronounced in the context of working with vulnerable communities.

Thought-provoking questions working with vulnerable communities

Vulnerability extends beyond individuals, emotions, and communities; it encompasses sensitive conversations, private topics, personal identities, and unique culture.

Understanding the impact of vulnerability on design research ethics is crucial. As a professional design researcher by training, it prompts me to contemplate three fundamental questions:

- How do we cultivate the appropriate manner, mindset, and behavior to communicate and connect respectfully with vulnerable communities?

- How do we establish a flexible and adaptable research protocol, encompassing empowering tools, creative methods, and appropriate project scope, to enable researchers and workshop facilitators to achieve workshop goals without imposing additional tension and pressure on vulnerable communities?

- How can we effectively empower vulnerable communities through the perspective of design researchers?

Adaptability, artifacts, and apprehension

I acknowledged the unique circumstances of each participant in the vulnerable community, with some belonging to low-income families, others dealing with mental health issues, some having dropped out of school, and other complex reasons.

As a workshop facilitator, I found myself navigating a role that overlaps between a design researcher, a social worker, and a psychologist.

In this article, I aim to share three insights on how to establish a suitable mindset for conducting participatory design workshops with vulnerable communities.

- Adaptability: Shift from being a host to a facilitator, maintaining workshop flexibility to create a sense of control.

- Artifacts: Harness the creative potential by recognizing the power of tangible creations.

- Apprehension: Empowerment stems from effectively holding space for participants.

Adaptability: Shift from being a host to a facilitator, maintaining workshop flexibility to create a sense of control.

The 18 teenage participants demonstrated high intelligence, with the majority openly and actively expressing their needs during the workshop. Only a few exhibited a bit of shyness.

“I need to take a 10-minute break to smoke.”

“Can you please repeat this part again?”

After a 10-minute bio break, some participants either failed to return or left in the middle of the workshop, while others remained using their phones. Despite possibly listening to the group discussions, their interaction style with peers and us, the workshop facilitators, varied in their own styles.

From this experience, I’ve learned the importance of adopting the role of a “facilitator” rather than a “host.” This entails guiding workshop discussions and flow with a more flexible approach.

Being adaptable and flexible has been an integral consideration, instilling a sense of controlled ambiance for participants, fostering ease, care, and respect.

For workshop facilitators, the challenge often lies in ensuring the achievement of goals and desired design outcomes, setting appropriate and feasible expectations, and establishing an effective research evaluation matrix for success.

Creating a sense of control during the workshop underscores the need for researchers to redesign workshop materials—including scheduling, exercises, tools, expectations, and time—as a spectrum. This approach allows for responsive adjustments to gauge and address any gaps that may arise.

Artifacts: Harness the creative potential by recognizing the power of tangible creations.

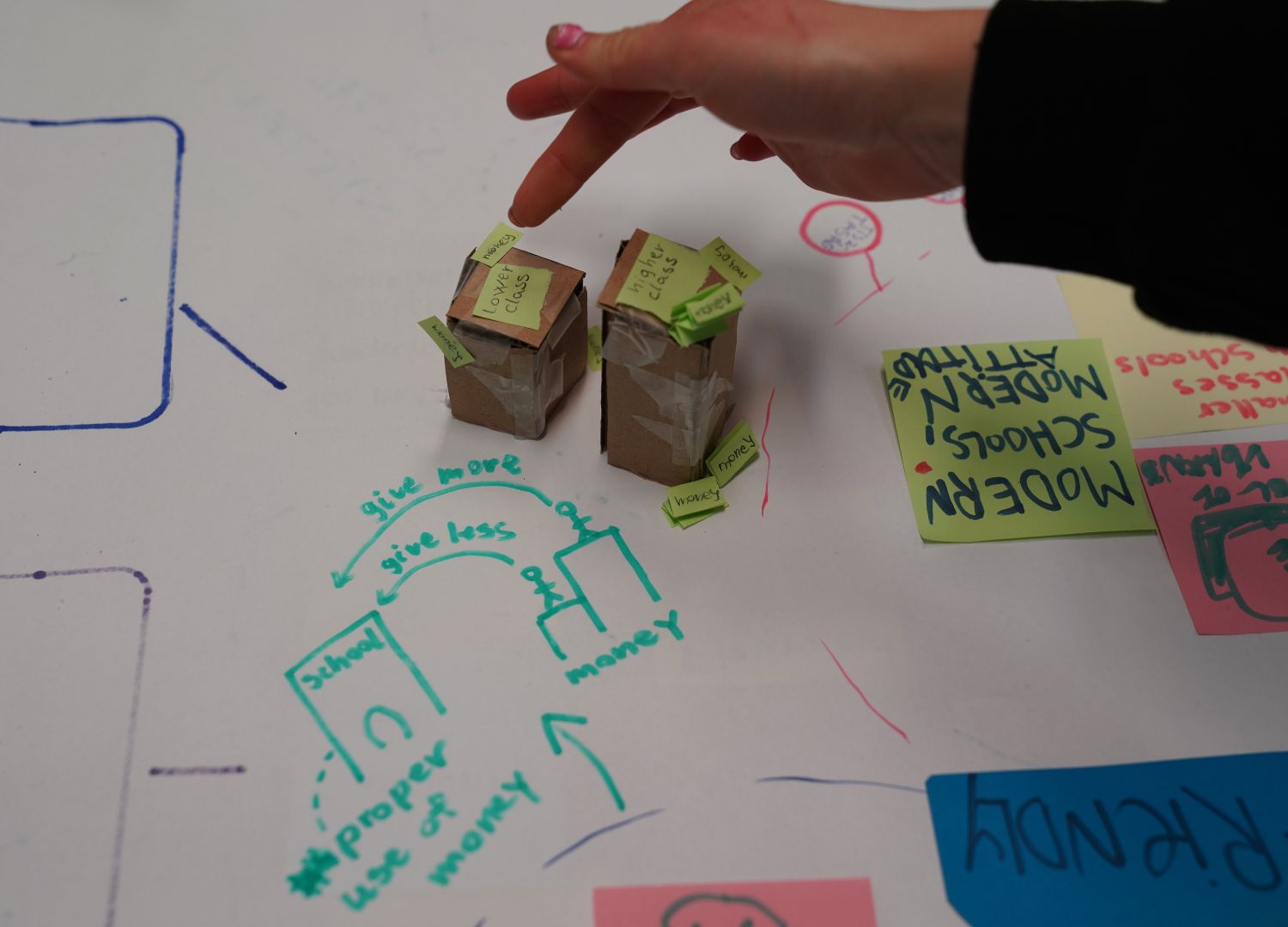

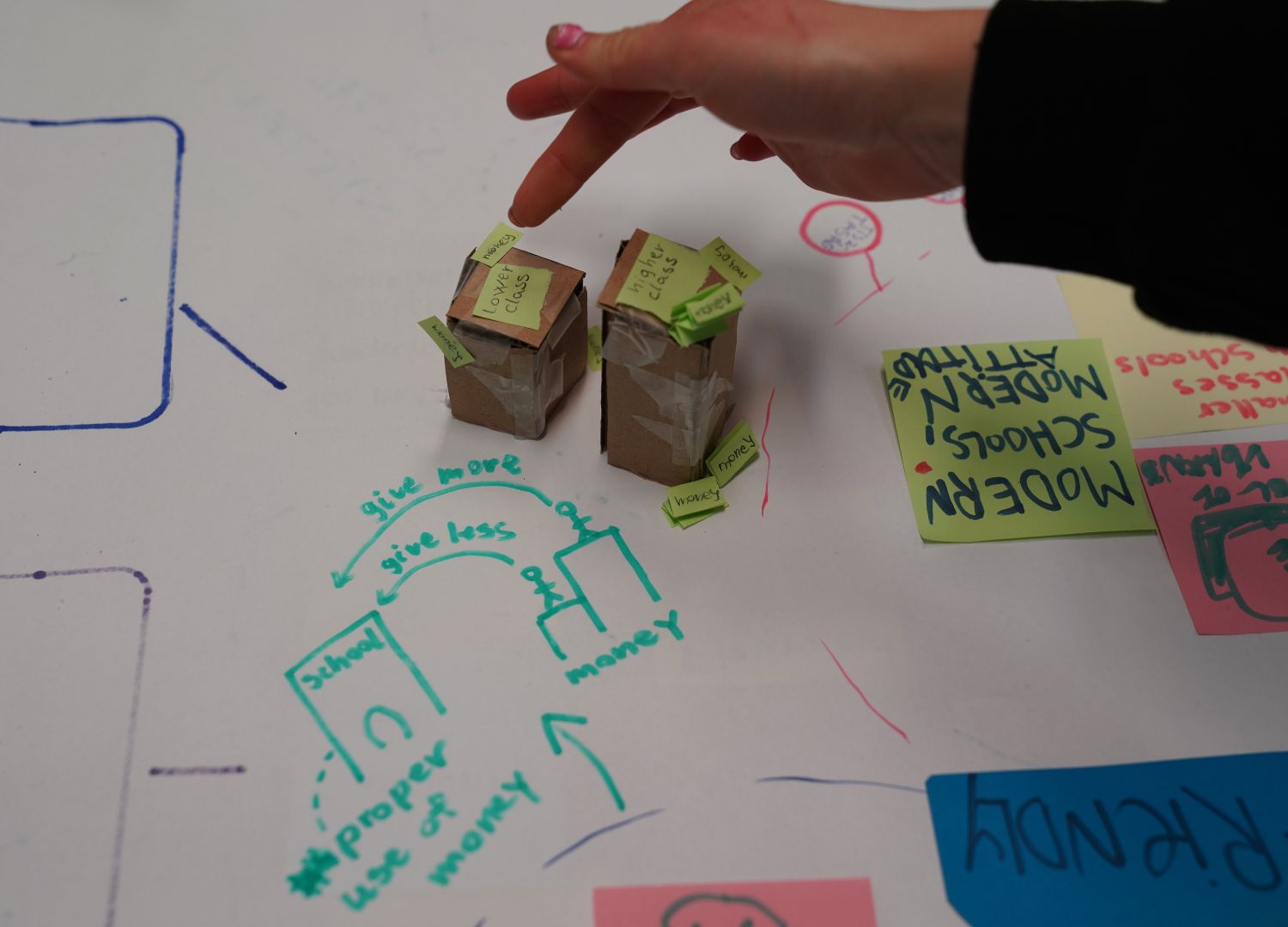

Drawing from my workshop observations, it is evident that tangibility enhances participant engagement with us and interaction within groups. The incorporation of tangible elements in the workshop, including printed Design for Longevity (D4L) cards and prototyping materials such as foam core boards, cardboard, LEGO, wooden blocks, and Post-its, notably elevated the level of participation in the workshop (Figure 4).

By using Post-its and posters, we introduced the concept of tangible artifacts to aid participants in jotting down notes or sketching ideas, enhancing their focus during the group discussions. These accessible prototyping materials served as valuable tools, enabling individuals to articulate their creative thoughts swiftly and cost-effectively.

Reflecting on the second week co-workshop, one participant demonstrated the power of tangibility by prototyping and translating into physical form her idea regarding inequitable education systems in Budapest.

In this scenario, she shared the design intent with me that a larger rectangular box represented individuals with higher social status and incomes, while multiple folded Post-its symbolized the financial contribution the wealthier group could make to the education system (Figure 5).

The efficacy of tangibility extends beyond vulnerable communities; it resonates with a broader audience, including non-vulnerable groups. The idea of “make to think and build to image” connecting to tactility is to engage our sense of touch to stimulate thinking and facilitate the construction of mental images for participants in general.

Apprehension: Empowerment stems from effectively holding space for participants.

In this research, Janka and I collaborated with a school teacher (social worker) serving as catalysts throughout the process. As highlighted earlier, our roles were more of facilitation than hosting the workshop.

As facilitators, how do we create a conducive and safe space or even hold the space for participants?

Being silent in the workshop environment, allowing participants to have a personal breathing space, and playing a background role as a passive observer might contribute to maintaining an accommodating safe and free atmosphere.

Most of the time during the workshop, I was learning in the context and set aside my concerns compared with the typical co-creation workshops I’ve done before to ensure that the participants could truly be themselves.

I would say that this task is not straightforward for me, especially considering my background as a trained professional designer. Continuously, I need to be mindful of delivering design solutions that cater to targeted users’ pain points and clients’ needs and expectations within the given context.

Understanding my role in working with vulnerable communities becomes important. As both a design researcher and workshop facilitator, I leverage my unique identity to establish boundaries—creating a tranquil, personal, and safe environment that allows them the freedom to think and express themselves with ease.

Summary: Design research, empathy, culture

“Design is not a profession but an attitude.” –László Moholy-Nagy, Vision in Motion 1947.

Similarly, the idea of Design for Vulnerability (D4V) represents a perception, attitude, and mindset aimed at helping us recognize the significance of elevating the essence of design value from individuals to societal levels.

Particularly in today’s context, the rapidity and implementation of emerging technologies often surpass the pace of our social infrastructure and even outgrow human attitude/mindset, such as the application of AI to replace many labor-intensive and repetitive jobs or opportunities. Consequently, the continual invention of new technologies might lead to unforeseeable social issues that may spiral out of control.

Moreover, we currently face a myriad of complex challenges such as war, climate change, aging, AI ethics, and more. In the era of longevity economics and industries dominated by services and AI, the roles and responsibilities of design have undergone a transformation to confront these issues that are increasingly intricate, multi-generational, systemic, and socioeconomically impactful.

To equip designers’ capabilities to solve these difficult challenges, our education systems need to nurture a future generation of multidisciplinary designers, and curricula should foster stronger empathy for and with people.

Meanwhile, designers and society at large should put more emphasis on the vulnerable communities in terms of relevant policies establishing financial platforms, physiological health, social welfare systems, community building, and culture and awareness shaping.

Acknowledgments

The preliminary research project receives sponsorship from the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME) Innovation Center and MOME Social Design Hub. The author extends gratitude to Lāsma Ivaska, Director of MOME Innovation Center; Dr. Bori Fehér DLA, Senior Research Fellow and Social Design Hub Lead at MOME; and Janka Csernák, Social Design Researcher. Appreciation is also expressed to the author’s MIT Ph.D. Committee for their great support: Professor Maria C. Yang, Dr. Joseph F. Coughlin, Professor Olivier de Weck, Professor Eric Klopfer, and Professor John Ochsendorf. The author also his expressed gratitude for the invaluable support received from Professor Sofie Hodara, who is associated with the College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University. Professor Hodara is not only acknowledged for her significant support but is also the co-creator of D4L cards.