Designing with standard parts: creating from what already exists

As the industry keeps producing more, perhaps we can find more creativity and value in making with what we have, rediscovering what our objects already offer.

The use of standard parts in design sits in a curious intersection of pragmatism and creativity. At first glance, the practice seems straightforward enough: designers select components that already exist in the world, manufactured to agreed-upon specifications, available from catalogues and suppliers, proven through use.

However, standard parts have also been used in the past decades as tools to free creativity, constraints that seem to limit forms but can actually generate new ideas. By working with the limitations of what already exists and is available, a designer can become ingenious with what he can or cannot make, and most importantly, it becomes a process that can be replicated or modified by others, democratising access to making.

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

Fundamentally, there are two ways of working with standard parts in design. The first is what we could call industrial utilitarianism, where standard parts like bolts and screws are chosen specifically for practical reasons: they are available worldwide, offer easy maintenance, and are affordable. They make the design process easier and universally understood.

This way of designing has also become an environmental necessity in recent times. The Right to Repair movement has made standardisation a political issue, highlighting how manufacturers who use proprietary components prevent independence and force consumers into cycles of replacement, while products built with standard parts democratise maintenance and extend product lifespans. Consider the difference between a smartphone and a bicycle: the smartphone is sealed and designed for replacement, while the bicycle celebrates its assemblage, which is intuitive and encourages repair.

The second way of working with pre-made parts happens when designers use these standard parts for aesthetic and conceptual reasons, aiming to create new objects from what already exists. In contrast with the first utilitarian approach, here the very existence of these parts becomes part of the design’s core framework, because of their cultural associations, because they impose constraints, because they are recognisable. This approach asks: what does it mean to create something from objects that already exist? How much transformation is required before we can claim to have made something new? Are selection and arrangement a means of creation in themselves?

A simple example that comes to mind is LEGO bricks. When used freely without predetermined instructions, they involve using a set number of options to be composed into something new, an act of creation. The bricks themselves are not as important as the possibilities a child sees in them.

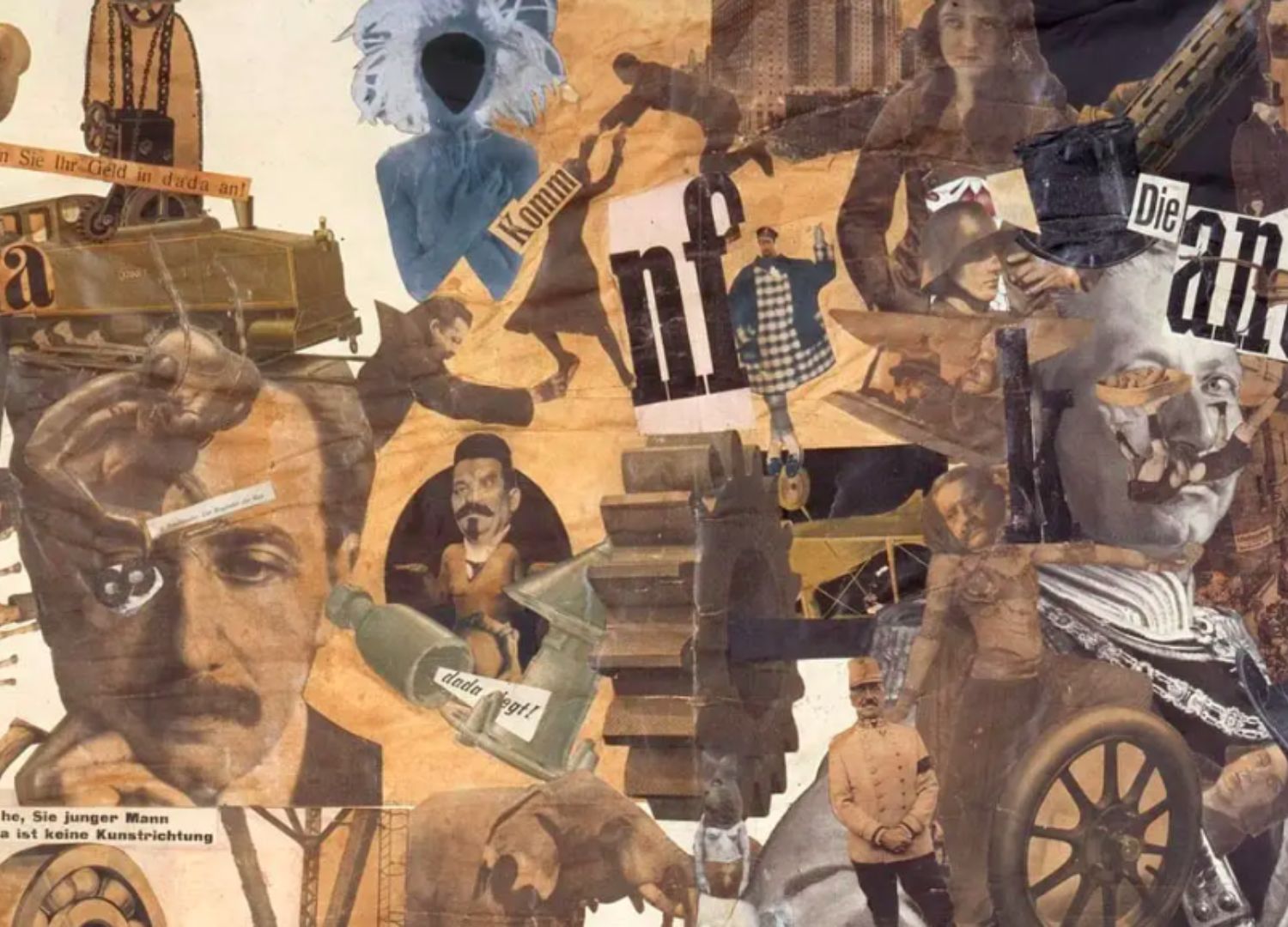

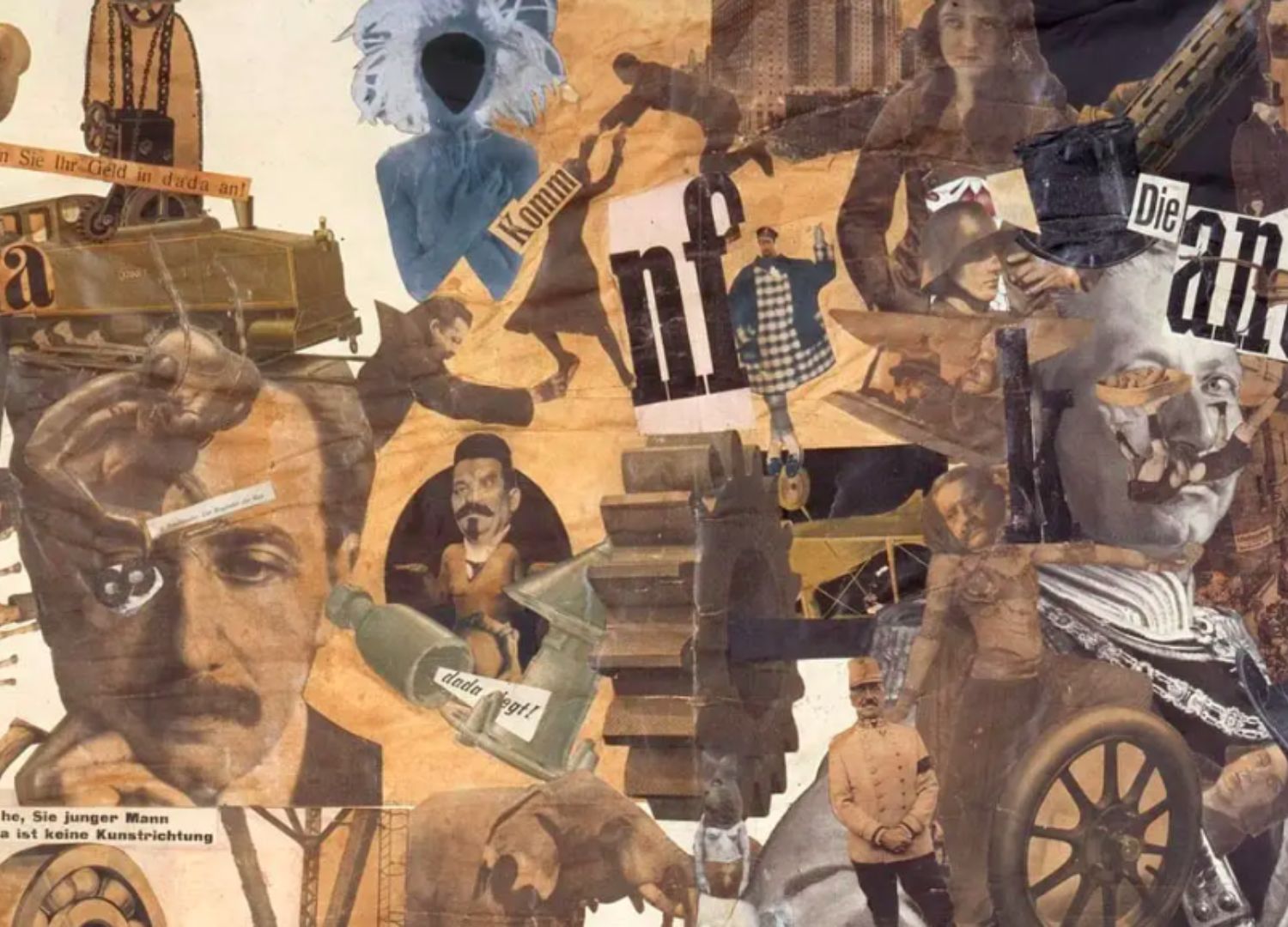

This conceptual use of standard parts has roots in the twentieth century, beginning with the provocations of Marcel Duchamp, Dadaism, and the readymade aesthetics. When the artist presented a urinal as a sculpture in 1917, it was entirely standard, mass-produced and virtually unaltered, it was simply positioned in a different context. This was a turning point in the art world, as art was no longer inherently related to craft and making but could also be a product of mental processes alone. In Dadaism, a common art form was the collage, which is another way of working with pre-existing materials, extrapolating them from their original meaning and placing them into a new context.

Oddly enough, this increase in limitations created more freedom in the arts. When options are more limited, creativity must work within defined boundaries, which often produce more focused, coherent, and ultimately more unexpected results. The Japanese aesthetic tradition understands this deeply in the concept of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in the imperfect, incomplete things that already exist. This framework suggests that perfection might lie in accepting what is available and finding ways to make that availability meaningful.

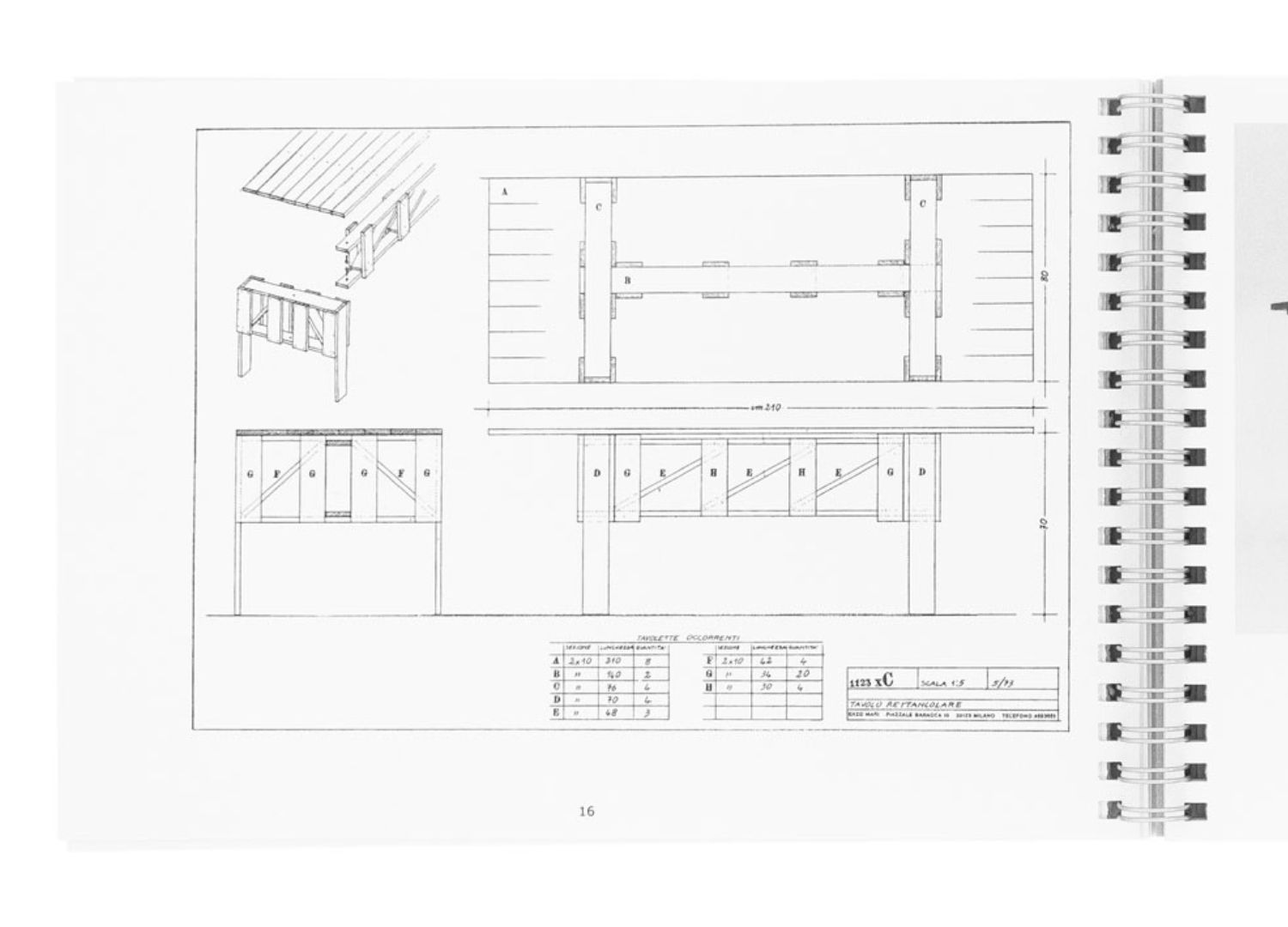

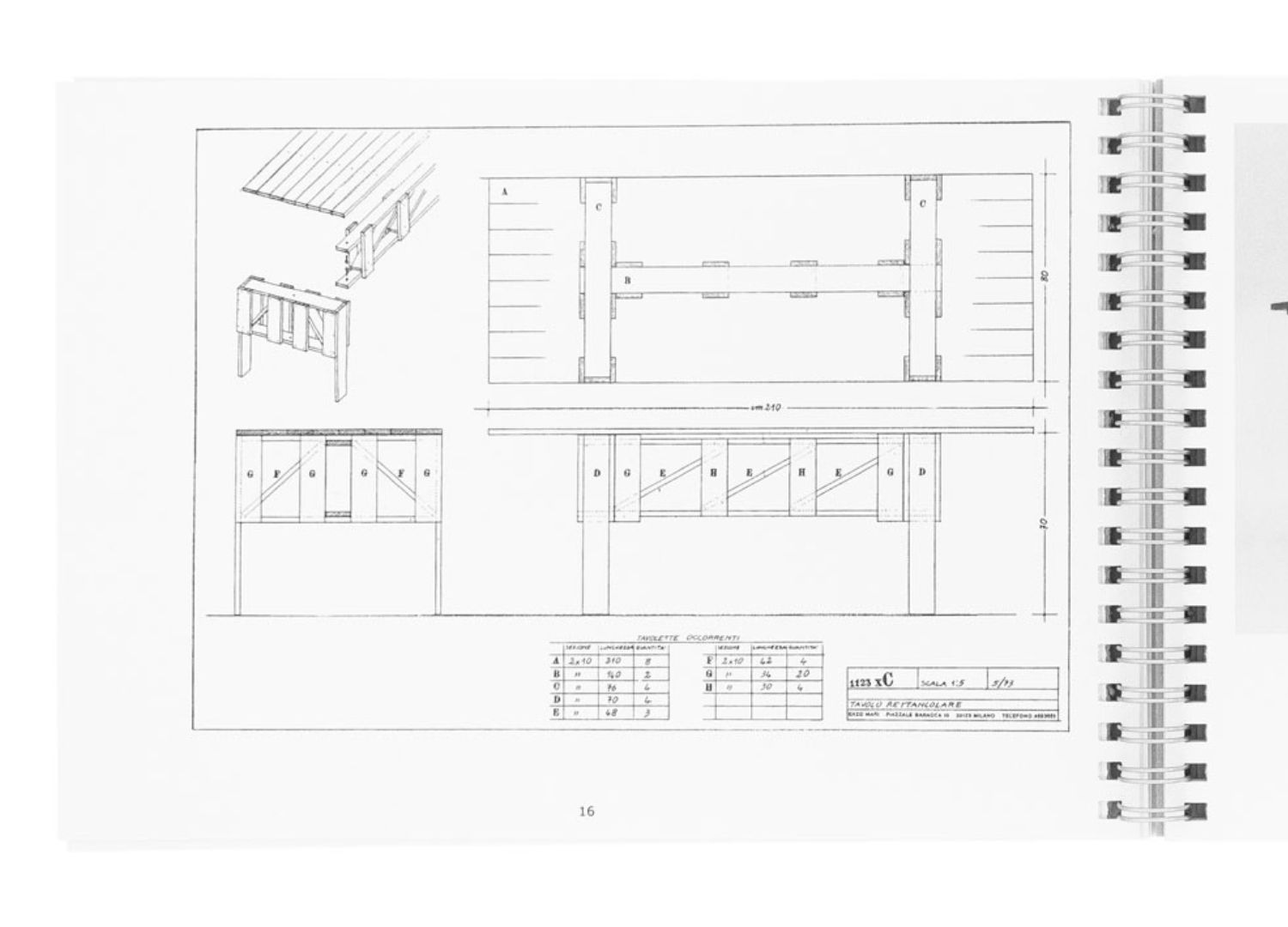

One of the design projects that has most thoroughly explored the implications of standard parts is Enzo Mari’s Autoprogettazione. Mari became frustrated by the inaccessibility of well-designed furniture to ordinary people, so in 1974 created 19 furniture designs that anyone could build using only materials available at any lumberyard: standard-dimension pine boards and common nails. By constraining himself to the most universally available materials, Mari democratised his own designs.

The project’s limitations become its expression: the visible nails become the design’s punctuation and rhythm, and the specific lumber dimensions are used in proportional harmony. If everyone has access to the same materials, what separates good design from bad design? The answer could be intelligence, a sense of proportion, the ability to create something useful. “Progettazione” is the Italian equivalent of “design”, but it also means the skill of “creating a project”, which is exactly the representation of Mari’s work.

Standard parts don’t just have to be industrial components like screws and nails, they can also be standard objects we encounter in our everyday lives. Tejo Remy’s Milk Bottle Lamp for Droog uses twelve standard Dutch milk bottles to create a ceiling light. Remy uses minimal arrangement to turn found objects into a designed product, which comments on recycling, domesticity, and Dutch material culture. Here, the standard parts are not really used for functionality, as the lamp’s entire concept is held together by these milk bottles; without them, it would be just a glass lamp.

There is also something generous about designs that reveal their own logic, that show how they were made, inviting understanding and even replication. Such designs respect their audiences, treating users as intelligent participants rather than passive consumers. The designer’s contribution is valuable but not exclusive.

Something interesting is that these standard parts can also be culturally created sometimes. IKEA’s Lack Table is one of the company’s most common and basic products, with a simple and practical geometric design. Because it is so ubiquitous, it has become a platform for creativity, with makers worldwide using it as a standard component for custom projects: stacking them into shelving units, creating desks or workbenches, or customising its surface aesthetic. The table has transcended its role as a product and become a raw material, a shared reference point.

Designing with standard parts requires the courage to be honest about one’s means and methods, to acknowledge dependence instead of claiming autonomy. This honesty runs counter to much of our cultural mythology about innovation, which emphasises breakthrough and disruption. But perhaps honesty serves us better than mythology, we need designs that we understand, that last, that can be repaired. We need material practices that circulate resources instead of consuming them.

The truth is that all creation builds on what already exists. Even the most innovative designs use materials that were not invented by the designer, manufacturing processes developed by others, and formal languages inherited from previous work, whether consciously or not. The designer who claims to create from nothing is either self-deceiving or dishonest. Designing with standard parts makes this dependence explicit, admitting that we work with available means, that our creativity lies in selection and combination rather than complete inventions. This admission is kind of a liberation, once the materials and components are set, you can focus on the real creative work: seeing possibilities that others have not seen before.