A suitcase that serves as a MANIFESTO, highlighting each migrant’s journey

“Social design goes beyond addressing issues of war; it also tackles critical matters like the climate crisis, gender identity, and accessibility” says Gjergji Gjoka.

I often wonder how designers can contribute to making the world a better place. I focus on them because I believe they have the tools to explore and translate their insights, ideas, and sensitivities into tangible outcomes. Gjergji Gjoka‘s story is no exception.

This young design student of Albanian origin chose to create a prototype of a migrant’s suitcase for his final university project. I was curious why he chose this theme and its physical representation—the theme of migration and the few belongings migrants often carry. Despite his young age, Gjoka shared insights that should be considered by others, especially in institutions and politics. Migration has always existed and will continue to exist, and there is a fundamental concept we often overlook: we all share the same planet.

The strength of socially-oriented design lies in its ability to solve problems, improve solutions, or share a powerful message, often related to minorities. This is exemplified in Gjergji Gjoka‘s project, and that is why I want to share it with you. Hopefully, he can serve as an inspiring example for many new designers entering the market and wondering how they can leave a positive, lasting impact on the planet. Good design endures beyond any trend.

What is your background? Why did you choose to study design?

Gjergji Gjoka:

“I attended a technical school for surveyors and then decided to enroll at NABA in Milan. My desire to become a designer was fueled by a lifelong curiosity. Whenever I looked at an object, I wondered about its construction, its cost, and why it had that specific design. Over time, I realized my true interest lay in the story behind the object: why it was located in a certain place, why it had particular dimensions, and what motivated me to select it. This quest for understanding led me to pursue a career in design.”

As a fresh graduate, in your opinion, what is the role of designers in today’s society? What should we expect from you?

Gjergji Gjoka:

“Before graduating, I experienced a crisis while searching for a thesis project idea. I felt that the world around me was saturated and didn’t need more useful objects, but rather items that provoke thought and tell a story. We are fortunate to be born in a privileged part of the world, but others are not as lucky. In my view, a designer’s goal is to stimulate reflection by creating projects that communicate through materials, colors, and aesthetic choices, rather than words. This approach can help highlight issues unfamiliar to us and shed light on the challenges faced by those born outside of Europe.”

For your final thesis, you developed a prototype for a migrant’s suitcase. What inspired this idea and why did you choose this project?

Gjergji Gjoka:

“For my thesis, the most significant project of my academic journey, I initially aimed to create something purely functional and aesthetically pleasing. However, I struggled to find a compelling narrative. One day, I turned my attention to my cultural and family history and realized I had a powerful story to tell: that of my father, who fled Albania in ’91 and arrived in Italy on a stolen fishing boat. My goal was not just to share his story but to also highlight the similar experiences of others who left their homeland, not for the pleasure of traveling, but out of necessity.”

What items should be included in a migrant’s suitcase? What design decisions were made for this project?

Gjergji Gjoka:

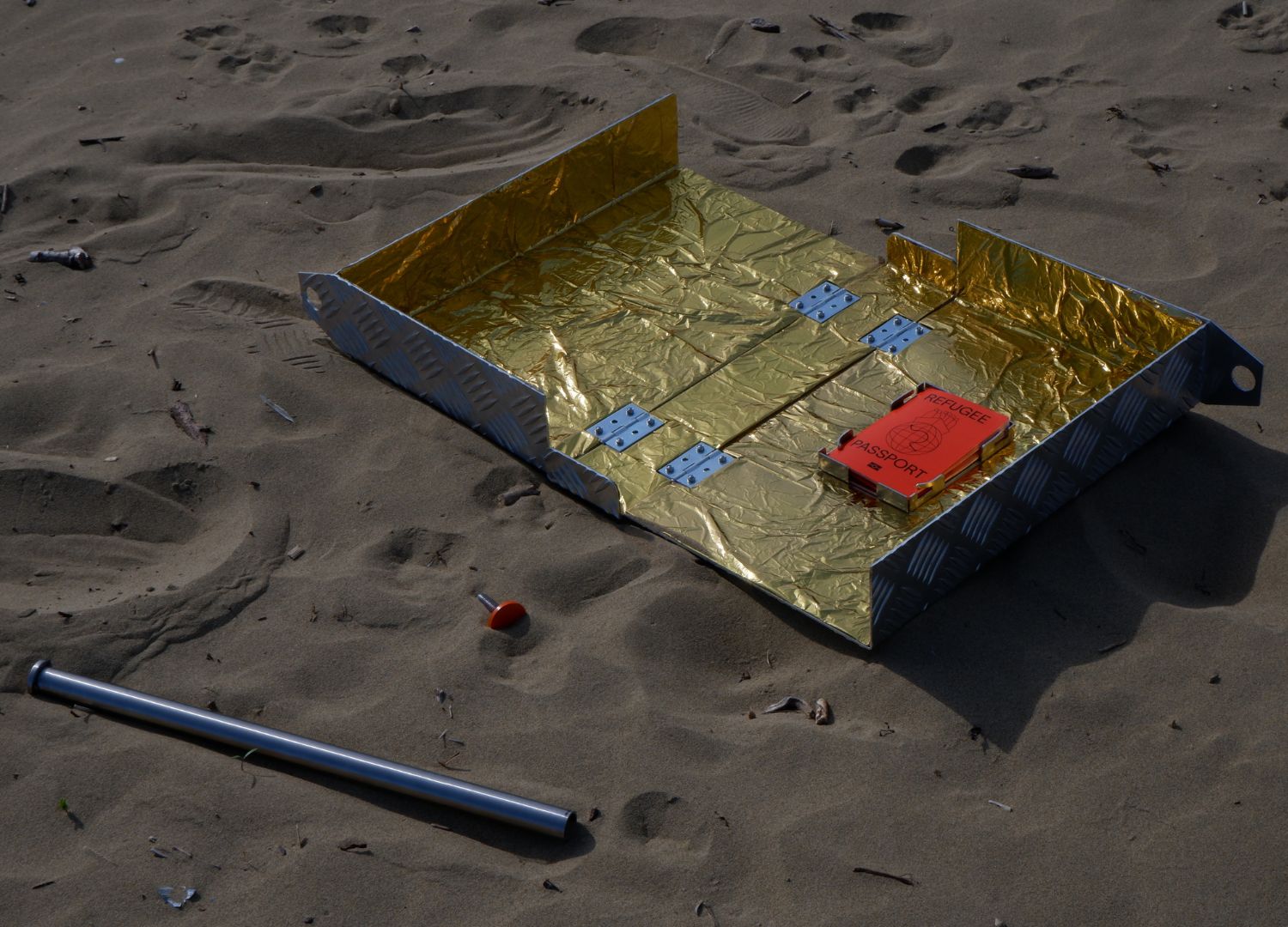

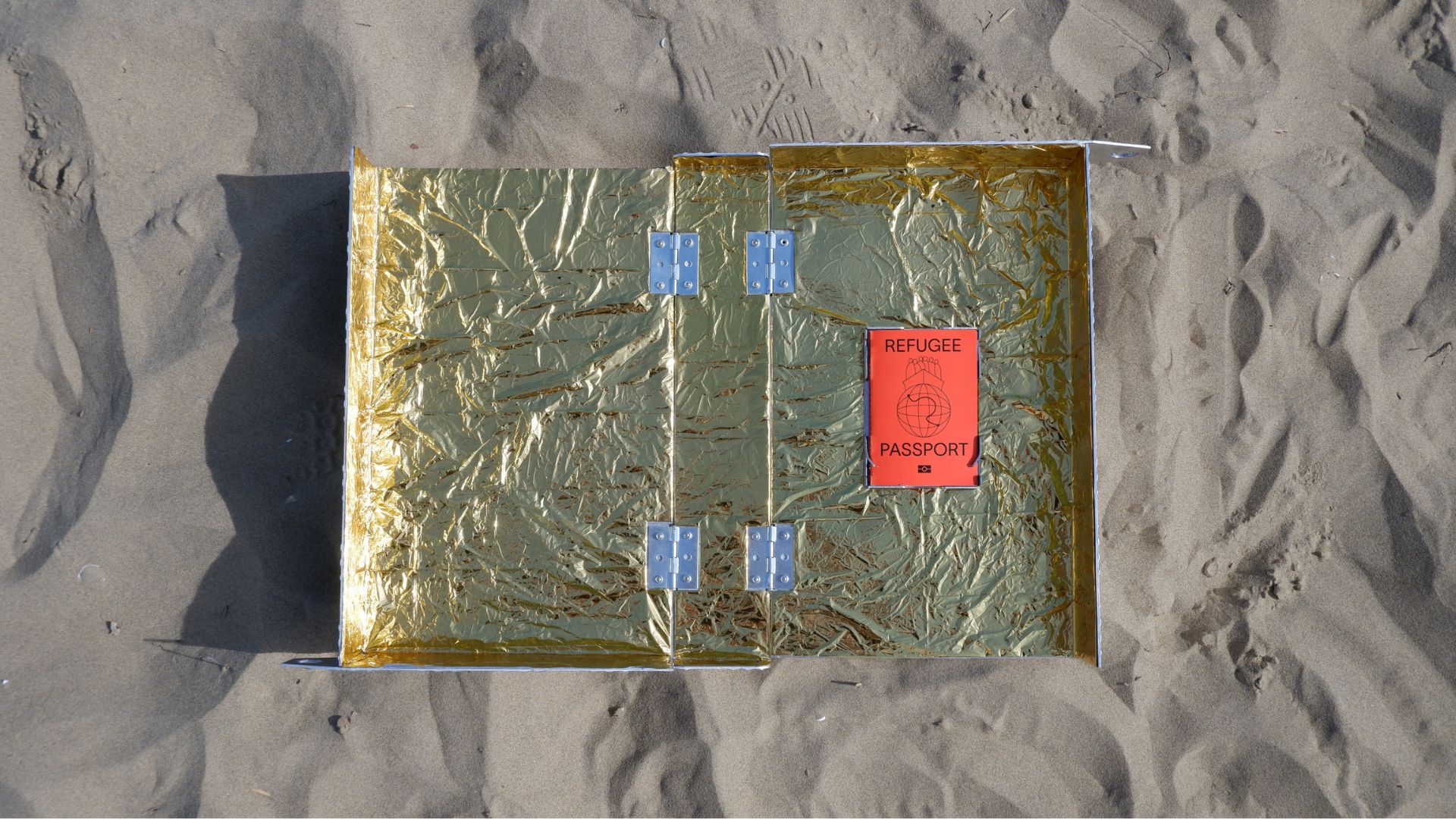

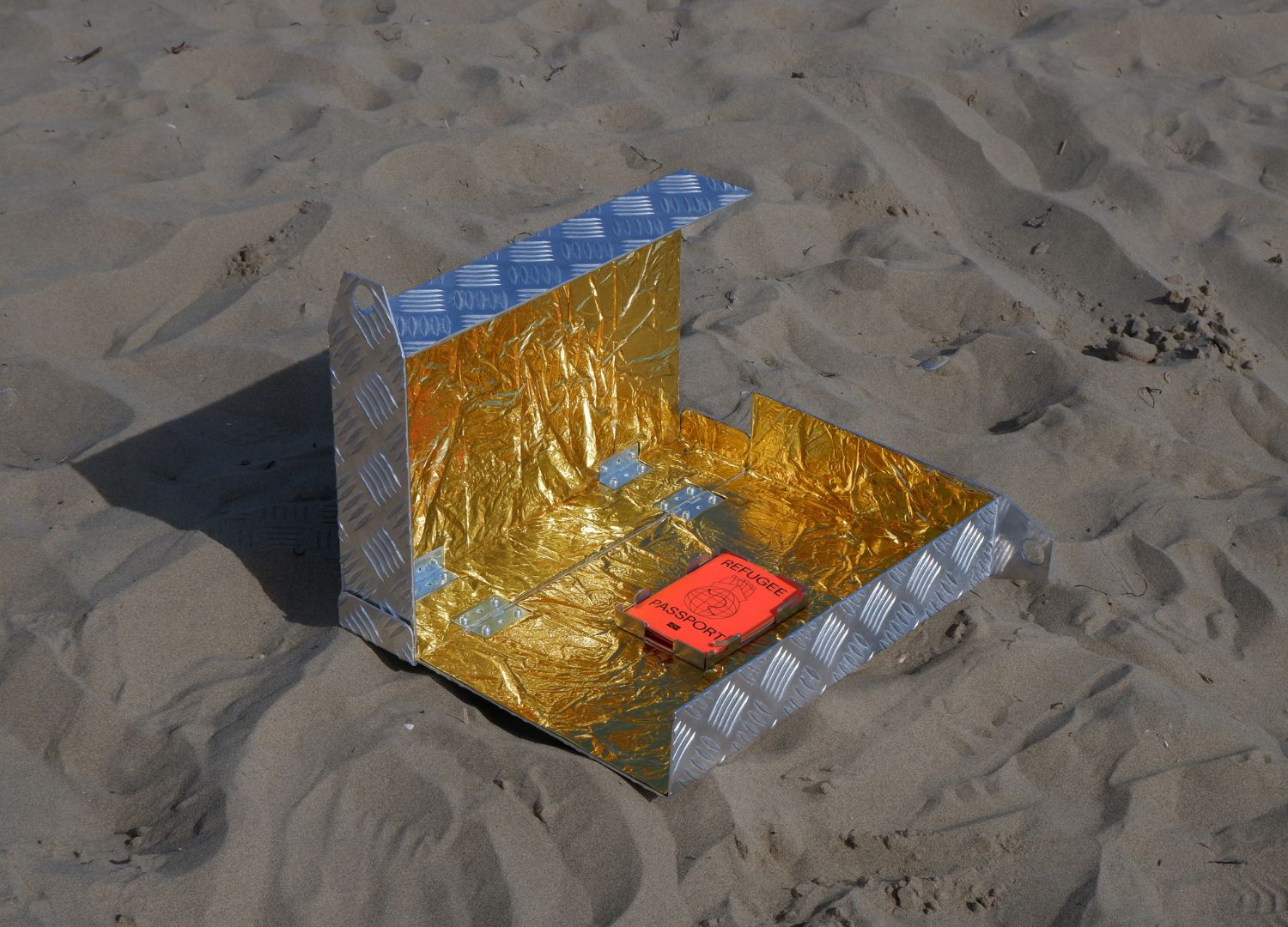

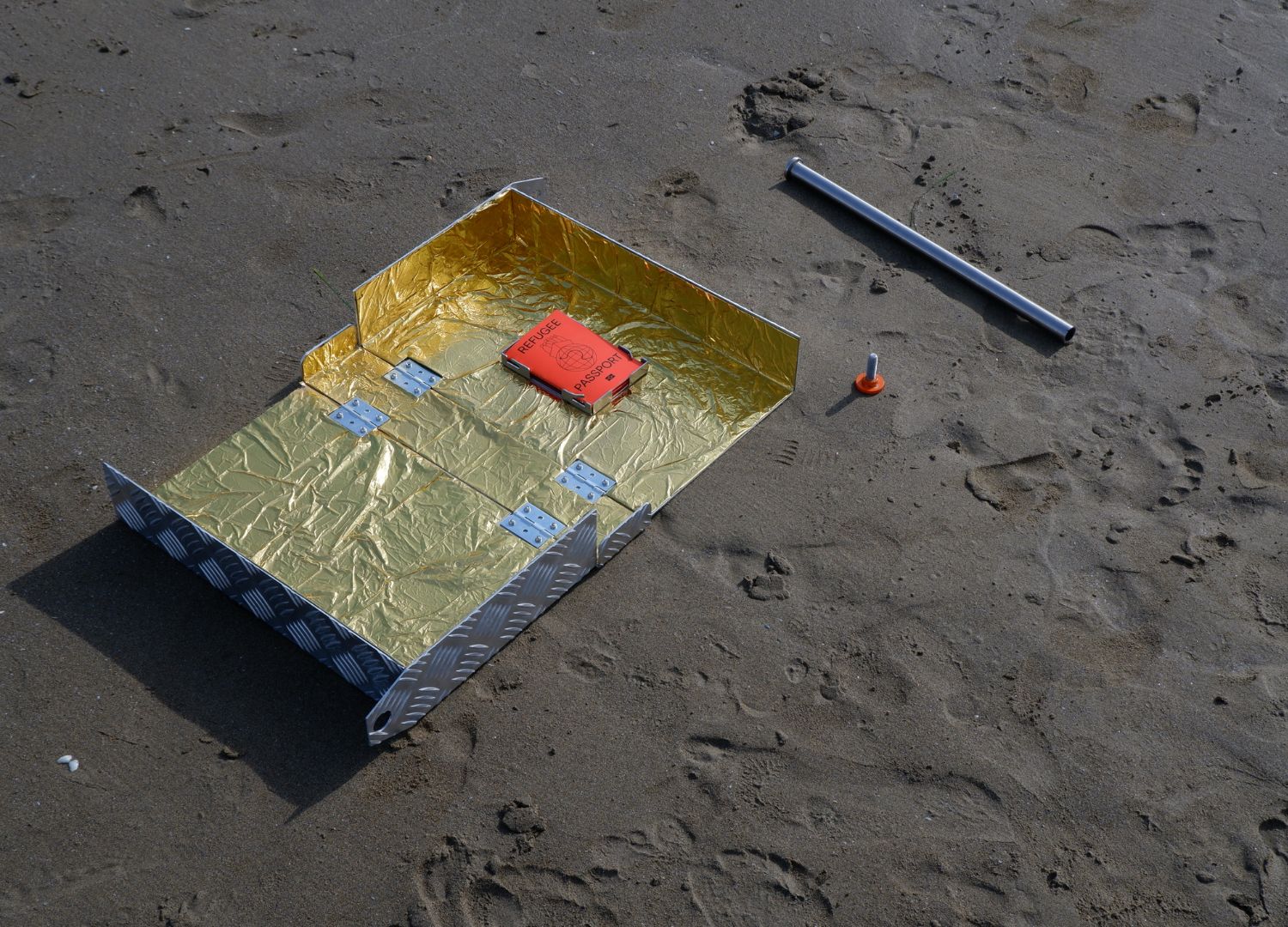

“The suitcase I designed wasn’t meant for actual use by a migrant; its purpose was to gather testimonies, stories, materials, and objects reflecting the migrant experience, merging them into a “MANIFESTO” that highlights each migrant’s journey. Constructed entirely of checker plate, a material typically used for walkable surfaces, the suitcase is lined with a thermal blanket—a fabric often associated with migrants, seen in images of them wrapped in such blankets. The suitcase is secured by a tube running through it.

Inside, there is one central item: the Refugee Passport. This passport is not just an identification document but also a travel diary, capturing the refugee’s journey. It tells the story of their travels, who they wished to bring with them, what they wanted to carry, and their hopes and dreams. This unique document facilitates entry into a new country while narrating the migrant’s story, explaining their reasons for leaving, the languages they speak, and their aspirations—essentially a curriculum vitae that enhances the refugee’s reception.”

Your idea stems from your father’s personal journey from Albania to Italy. If he had come from a different country, would you have designed the suitcase differently? Why?

Gjergji Gjoka:

“My father’s story served as the initial spark to identify the “problem” I wanted to address as a designer. I soon shifted my focus away from his specific background, aiming to create a universal suitcase that could hold a universal passport. For the design, I sought out testimonies from Syrian, Eritrean, and Cameroonian refugees, among others. The use of a tube as the lock was inspired by refugees’ accounts of enduring violence with batons and tubes, making it a central feature. Removing the tube allows the traveler to open the suitcase and access their passport, symbolizing the freedom and autonomy they seek. While my father’s story and heritage minimally influenced the object’s form and aesthetics, they deeply motivated me to convey this testimony as effectively as possible.”

There is a growing focus on social design. In your view, what are the most pressing social issues that deserve more attention from designers?

Gjergji Gjoka:

“In today’s landscape, fraught with increasingly urgent social challenges, the ethical responsibility of designers stands out prominently. Design transcends mere aesthetics and functionality, evolving into a powerful tool for raising awareness and driving change. As designer Philippe Starck aptly puts it: “I am a designer and design is my only weapon, so I use it to talk about what I consider important.” His “Gun Lamp” project exemplifies how design can convey messages of peace and counteract the culture of violence. Social design goes beyond addressing issues of war; it also tackles critical matters like the climate crisis, gender identity, and accessibility.

By creating thoughtful objects and spaces, designers can meet tangible needs while also telling stories, provoking thought, and increasing awareness about these issues. This approach is not just about making practically “useful” items, but about crafting tools that prompt reflection, highlight often overlooked problems, and foster a sense of individual and collective responsibility (read also about our ‘Enhance – Design for Social Impact’ exhibition). Thus, social design becomes a catalyst for change, bridging the aesthetic and ethical realms to positively impact society and help build a better future.”