Choreographing power: government innovation through a Design lens

The recent turbulent U.S. presidential election has drawn intense attention, not only from Americans but from a global audience. How can we remain uninvolved in such a pivotal conversation? How do we ensure the safety and well-being of ourselves, our families, and others, regardless of ethnicity, gender, or social status—especially when we are surrounded by wars and critical political, economic, and social challenges worldwide?

My interest and intention lie less in politics and more in the design and innovation aspects within the political sphere. The complexity and interconnectedness of these issues remind me of the themes surrounding government design and social innovation. This topic offers a thoughtful way for me to clear my mind and reflect on my current design research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Designing for government innovation is a vast, challenging, and sometimes intimidating area for designers and researchers. Although I am not an expert, I have gained relevant experience through projects focused on government innovation and social impact during my work with IDEO, MIT GOV/LAB, and my own side projects.

Government Innovation – 3 key learnings:

Design for Whom?

Identify, Understand, and Manage a Complex Network of Stakeholders

MIT GOV/LAB launched the Governance Innovation Initiative to explore the relationship between creative problem-solving process, government, and civil society, aiming to make governance more transparent, accountable, and responsive through design.

In the summer of 2022, I had the opportunity to work briefly with MIT GOV/LAB on a governance innovation project alongside Carlos Centeno, Cory Ventres-Pake, and Awab Elmesbah, under the guidance of Professor Lily L. Tsai, Department of Political Science at MIT. Our objective was to create a design-thinking curriculum for governments in Africa (Figure 1).

I participated during the early stages of the project, at the beginning of the post-pandemic period. At that moment, international travel remained uncertain, making fieldwork with African governments challenging.

Despite working collaboratively at MIT GOV/LAB, I found it challenging to identify and understand the key stakeholders involved. Layers of email communication and unfamiliarity with contacts on the client (government) side added to the confusion. Information was scattered, and the decision-making structure within the government, organizations, sponsors, and project team was unclear.

Who were we specifically designing for—government leaders, policymakers, legislators, sponsors, citizens or all of them?

Transparent and accessible communication is crucial for identifying stakeholders effectively. Determining the contact persons on both sides, whether they are reliable, responsive, and influential within or beyond their organization, is critical. Stakeholders, communication, and power are interconnected, tied closely to motivation.

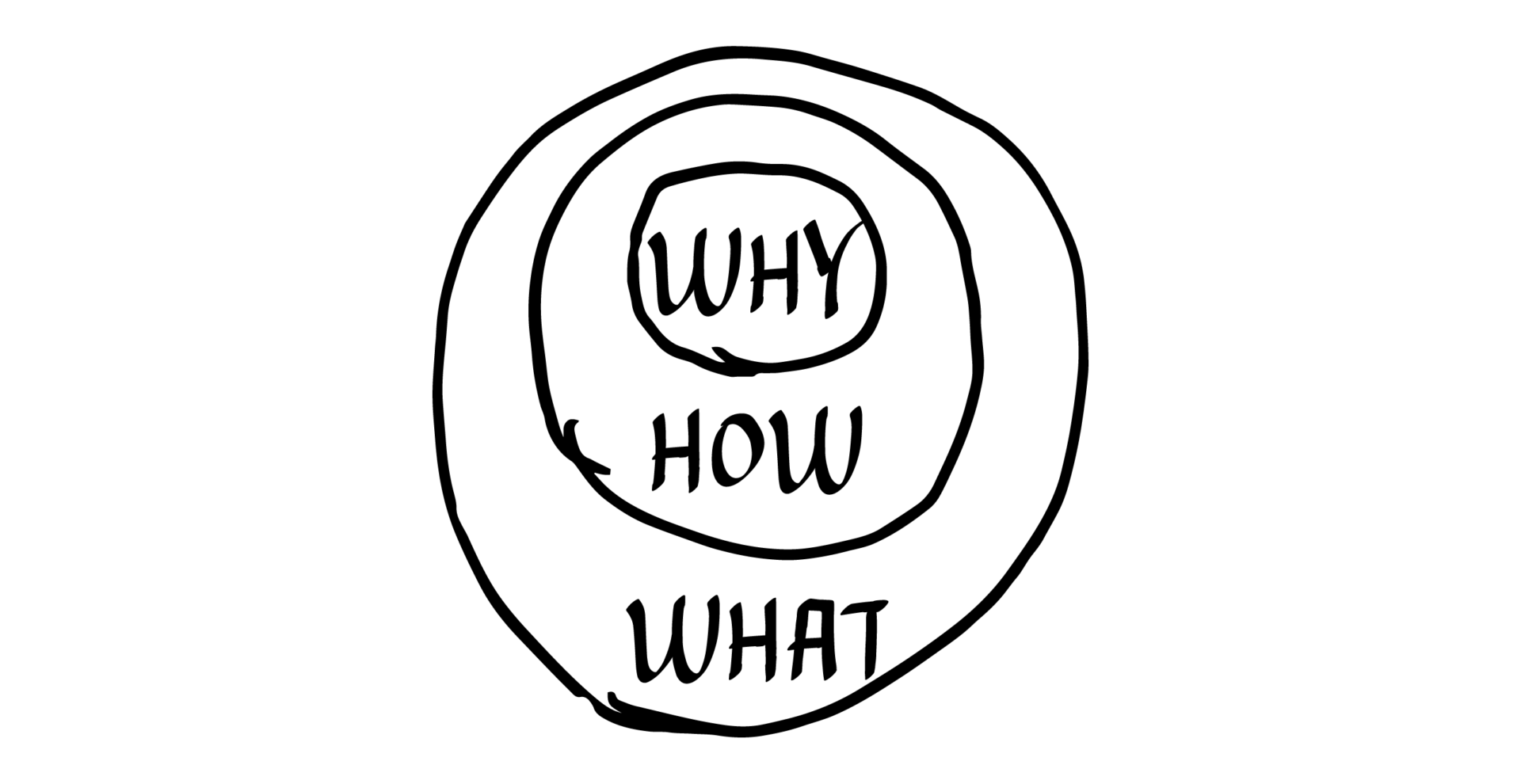

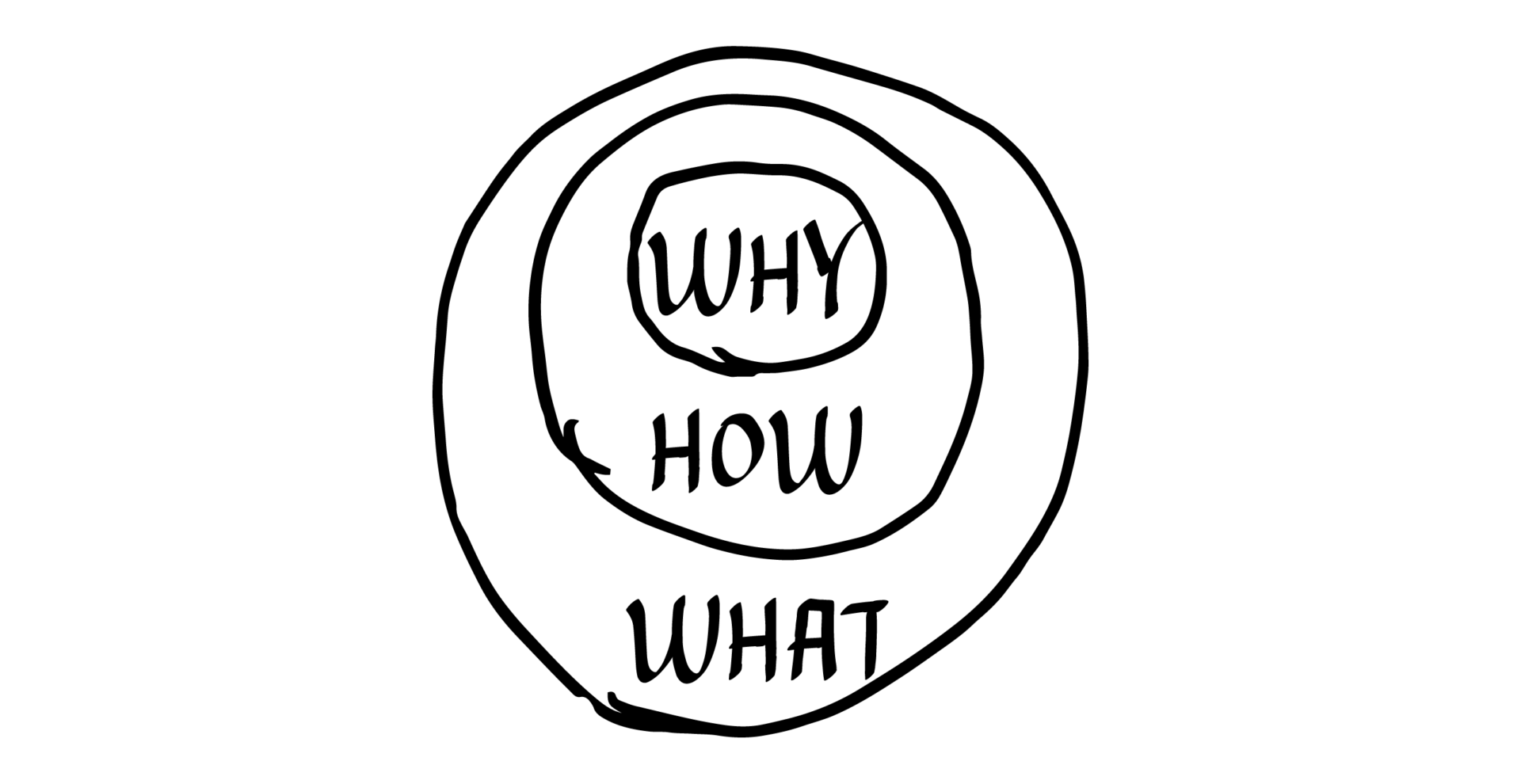

Simon Sinek’s Golden Circle framework resonates with this process (Figure 2). It starts with a simple question: “Why?” The outer circle, “What,” represents more tangible, easily understood outcomes. The middle circle, “How,” represents the approach or process to achieve these foreseeable outcomes. The inner circle, “Why,” is the purpose—the true source of motivation and power.

Obviously, purpose and motivation are deeply connected. Once we understand our client’s purpose—government leaders in this case—we can more effectively identify the key stakeholders within this complex organizational system.

Identifying, understanding, and analyzing key stakeholders and their relationships are crucial, especially before fieldwork begins. Designers or researchers need to know what they are looking for, how they intend to share their outcomes, and the deliverables they are expected to meet.

At MIT GOV/LAB, we spent three months not only designing the curriculum for the government innovation but also understanding the needs of our key stakeholders, including our project sponsor (the Gates Foundation), client (the African government), and MIT GOV/LAB.

Design for What?

Deliver Outcomes in Meaningful Forms Beyond Products, Services, and Systems

The format of design outcomes matters. Today, people have numerous options, tools, and methods to apply and appreciate the outcomes and processes of design. With Apple’s launch of Vision Pro, Meta’s Quest Pro, and other tech companies entering the AR/VR space, individuals now have access to more immersive and customized experiences.

At the same time, with the widespread adoption of smartphones, mobile digital experiences have become a universal experience and a common design language. Almost everyone has at least one smart device in their hands.

For instance, the City of Boston partnered with IDEO, a global design firm, to redesign the digital wayfinding of the government website, emphasizing a citizen-centered approach. The goal was to empower individuals to effortlessly navigate the site, find answers, and position the platform as a community hub.

These examples highlight the importance of how designers and researchers deliver their outcomes for government innovation projects and research. Beyond traditional formats like white papers, reports, or other static formats, there are more interactive, engaging, and meaningful approaches to present results—approaches that can evolve over time.

During my time at IDEO, in 2018, IDEO, ATÖLYE, and Palmwood co-organized and launched the Design Gov program for government innovation in Dubai (Figure 3). With versatile outputs ranging from design co-creation workshops to toolkit development, the level of participation among government leaders was significantly elevated, impacting core leadership. The program led to the co-hosting of government events, activities, and even transformed the design curriculum and policies.

In my view, designing for government-related projects and research often mean designing for groups of people with shared interests, benefits, and beliefs—individuals whose decisions can have transformative effects at a national level.

There are many possible formats—physical, virtual, or hybrid—that span products, services, and systems. Importantly, we should ask ourselves: what do we truly want to deliver to meaningfully and respectfully “scale” our positive influence? Is it products, services, systems, or perhaps broader connections to emerging technologies like AR/VR experiences?

Design for How Long?

Build Lasting Social Impact through Thoughtful Design Conditions

How can we create sustainable, system-level impact from government-related innovation projects? This is a question to consider. From my experience, the outcomes of most projects often include hosting one-off workshops, testing design toolkits, or co-publishing white papers.

Beyond these creative activities, how can we develop more actionable plans to evaluate the design solutions? What other options can we experiment with to make our impact more substantial and lasting? I am still exploring these questions myself.

One approach I’ve experimented with is creating a supportive and safe environment with secured funding and trustworthy leadership to facilitate co-creation workshops involving government and industry leaders.

For example, since 2023, I have collaborated with Shih Chien University and the Taipei City Government to explore how to build an AgeTech city and create a longevity-friendly urban experience.

That same year, I also worked with a research team at the Taiwan Design Research Institute (TDRI) to envision the future of Taiwan’s healthcare system through the lens of longevity. We invited medical doctors, caregivers, care recipients (mostly older adults), medical service providers, and service designers to collaborate on this complex topic.

Although it was only a three-hour design workshop, our goal was to at least create a positive momentum—to raise local government awareness and encourage modifications or changes to current policies, public services, and service design.

Design as Democratic Inquiry

I explore governance innovation through a design lens, focusing on the challenges and opportunities of integrating design approaches into government processes. The article highlights three key learnings:

- Identify, understand, and manage a complex network of stakeholders.

- Deliver outcomes in meaningful forms beyond products, services, and systems.

- Build lasting social impact through thoughtful design conditions.

These learnings are informed by my previous work with MIT GOV/LAB, IDEO, and other side projects, underscoring the importance of considering clear stakeholder communication and impactful delivery methods to enhance government transparency and accountability.

These reflections remind me of Professor Carl DiSalvo’s book Design as Democratic Inquiry (Figure 4). In it, DiSalvo used design as a mode of inquiry to explore the intersection of design and democracy, offering thought-provoking perspectives and methodologies.

He further examined the practice and conceptualization of design as part of democratic inquiry, mainly when dealing with complex, systemic socioeconomic projects. He viewed the design for social impact projects as emerging from the interplay of individuals, institutions, and ideologies.

DiSalvo uses the term “civics” to mean “democracy on a micro-scale,” referring to the contextual or situated experiences that foster unity, collective agency, and a sense of community. He suggests that design experiments in civics are creative practices aimed at reconfiguring our communal existence, framing them as methods of democratic inquiry through design.

I agree that design experiments in civics or government innovation intricately weave together imaginative creation, political theory, and social structures (Figure 5). I also consider design an applied science that stands alongside art, craft, writing, and other creative disciplines as a legitimate form of imaginative creation.

When we rethink the design of a democratic inquiry tool for government innovation, we envision a tool that connects civics with purposeful creation, advancing collective agency and community engagement within governance.

While design’s role in civics and government innovation may not align perfectly with the strict boundaries of science, the aim is to cultivate a design practice that is dynamic, imaginative, inherently political, and deeply respectful.