From photogrammetry to Pi-shaped designers: lessons in future-oriented design

How photogrammetry, immersive environments, and cross-disciplinary education are reshaping the future of Design for Longevity.

At Dubai Design Week, I encountered three lenses that reframed how we might design for multigenerational futures: embodied learning through photogrammetry, immersive narrative environments, and cross-disciplinary design education.

These experiences—co-facilitating a Design for Longevity (D4L): Unclock workshop, visiting the Museum of the Future, and attending an education forum at the Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation (DIDI)—revealed how design can help us rethink aging, participation, and the evolving role of the designer.

Together, these experiences and reflections inform three key learnings about service and experience design from Dubai:

Photogrammetry – Learnings:

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

Embodied learning: reimagining longevity through photogrammetry

In the workshop, Professor Sofie Hodara and I introduced the Design for Longevity (D4L) Unclock Framework (Lee, 2025) and paired it with Scaniverse, a mobile photogrammetry app, to offer participants a new way of perceiving the Dubai Design Week campus.

The three-hour session (13:00–16:00) introduced participants to the intentions behind D4L and demonstrated how accessible tools such as photogrammetry can function both as research methods and as sources of design inspiration.

Photogrammetry refers to the creation of 3D models from multiple 2D photographs. Using specialized software, spatial information—including depth, scale, and positional relationships—is analyzed to reconstruct physical objects or environments.

When used with a smartphone, photogrammetry can complement ethnographic and design research methods such as mind mapping (Buzan, 1974, 1993) and service blueprinting (Shostack, 1984) to document and interpret environments connected to longevity challenges.

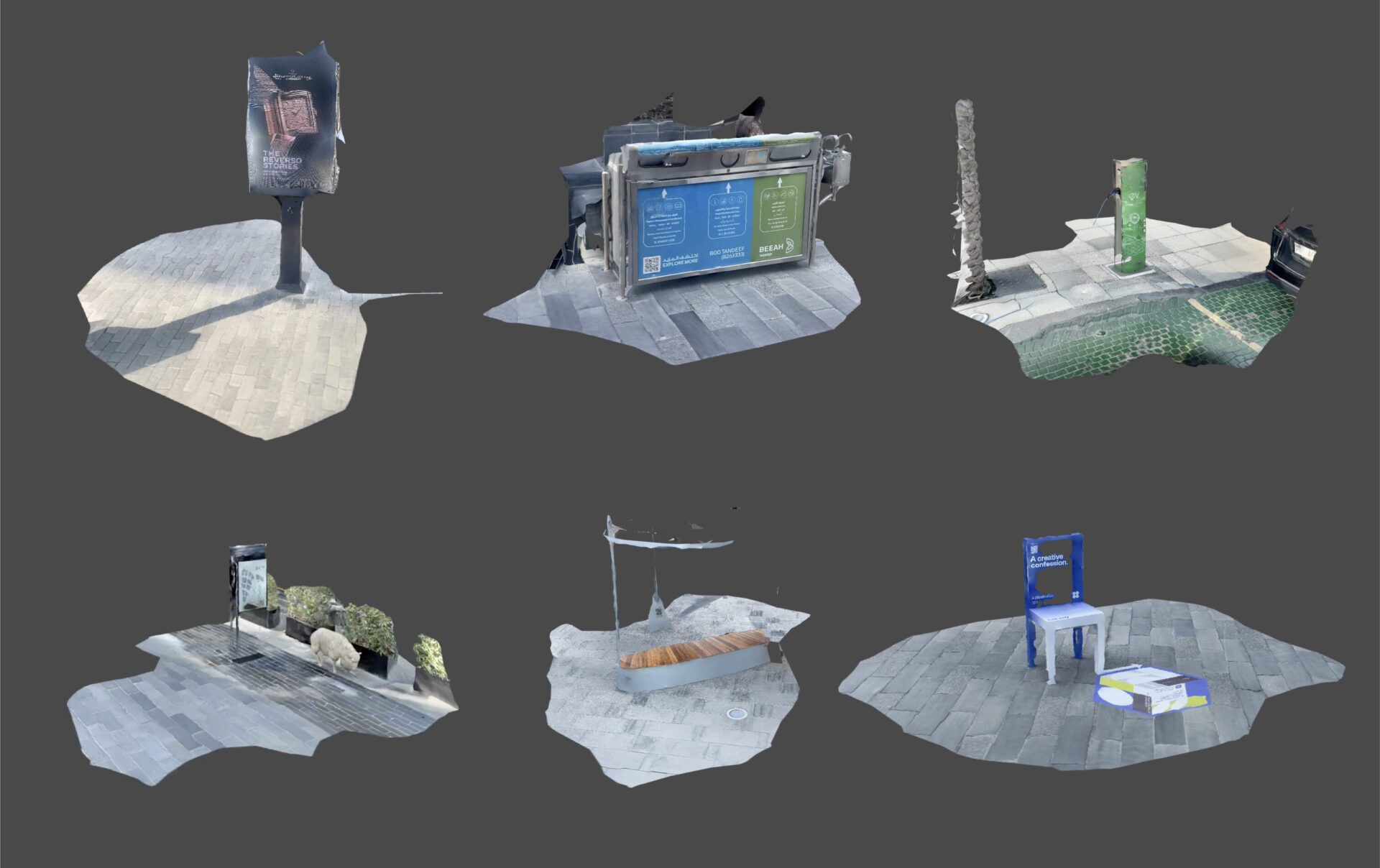

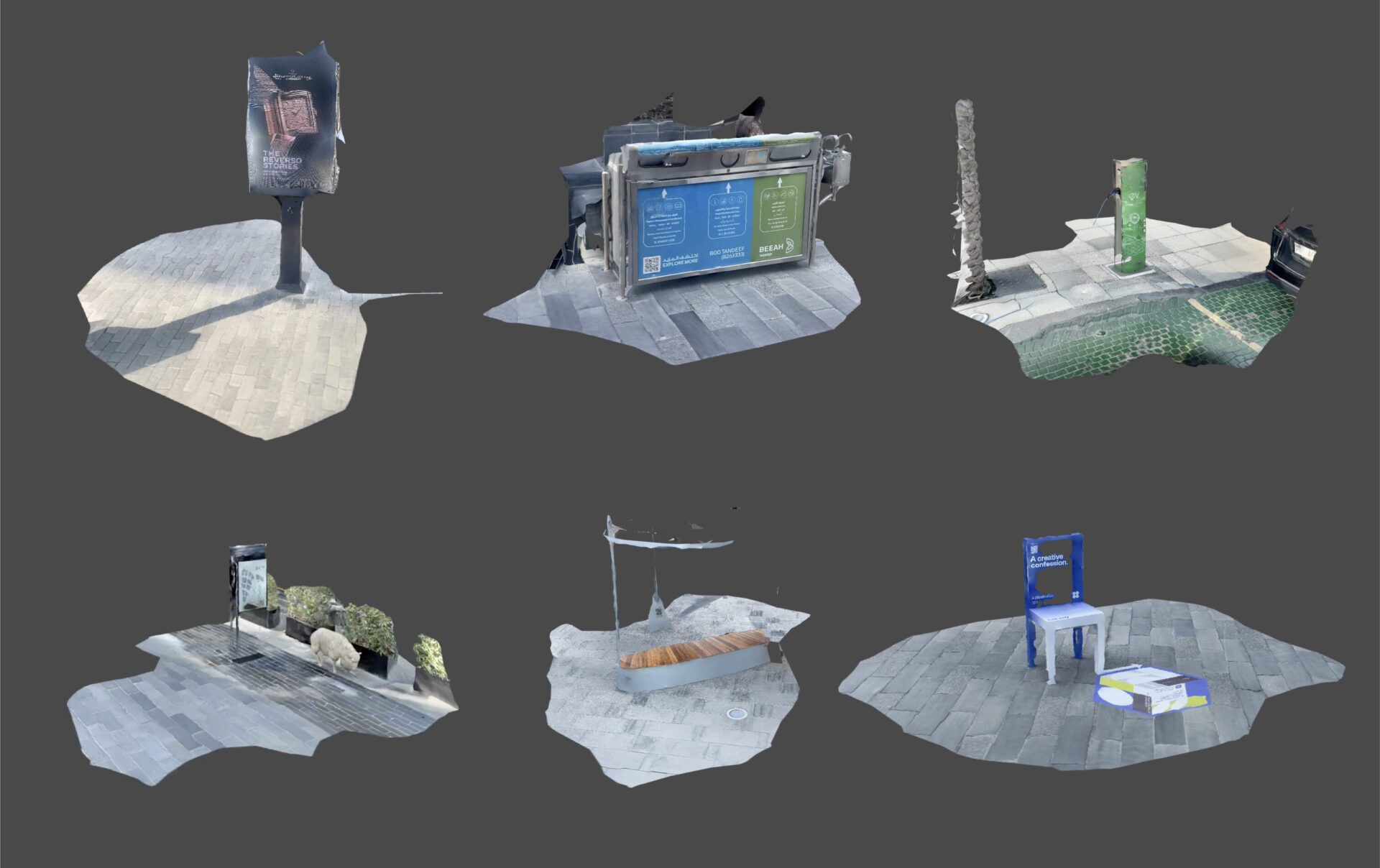

By systematically scanning a chosen site in Dubai Design Week campus to generate a 3D model, design researchers engage in a “slow,” evidence-driven observational process (Figure 2). This approach facilitates reflection on how longevity-related challenges manifest in everyday spaces, helping to identify opportunities for design interventions.

Although three hours may sound long, the time passed quickly due to the workshop’s dynamic structure—combining a mini-lecture, hands-on activities, and individual sharing—which supported a high level of engagement.

We opened with a 30-minute lecture to establish the conceptual foundations of D4L, longevity planning, and the urban exposome, and to encourage reframing aging beyond chronological years, to diverse life stages and trajectories (Figure 3).

For the hands-on component, participants had 30 minutes to use their smartphones to scan their surroundings and share their resulting 3D models (Figure 4). As Sofie noted, photogrammetry requires the body to move through space in order to capture it, an engagement that aligns with principles of bodystorming and embodied interaction.

This physical involvement was a key part of the workshop’s immersive and participatory nature. In this context, the process and act of scanning—looking closely, walking, circling, observing—was more important than the resolution or technical perfection of the final model.

Reflecting on the participatory co-creation experience at Dubai Design Week, I realized that my motivation has shifted. Whereas I once approached workshops primarily with the mindset of “I want to learn,” I now see the deeper value in co-creating peer learning environments. A workshop can serve as an experimental and generative space, abstract at times, but deeply inspirational, where knowledge emerges collectively through shared exploration (Figure 5).

Curated immersive experience for Museum Exploration

In addition to hosting the workshop, I visited the Museum of the Future, which opened in February 2022. The building’s oval form resembles a human eye, symbolizing a shared vision for the future. Arabic calligraphy wraps both the exterior façade and interior surfaces, embedding the museum within Dubai’s cultural and technological identity (Figure 6).

Given the building’s complex structural geometry, the exhibition team developed a “box within a box” spatial strategy. This allows each floor to offer a distinct experiential world without interfering with the integrity of the curved calligraphic envelope.

To streamline entry, I purchased a fast-track pass. The wristband, serving as both ticket and access credential for parking and storage, immediately reminded me of fast-track systems at Disneyland and Universal Studios. The museum experience itself also echoed that theme-park-like level of immersion. With the wristband, visitors can activate interactive stations designed to extend the narrative (Figure 7).

Across the museum, physical artifacts, such as staging consoles, seating installations, and reflective surfaces, are integrated with projection mapping, creating a seamless and sensorial environment (Figure 8).

One gallery invites visitors to explore the five senses through “connection therapy.” For instance, feeling therapy uses ultrasound-based haptic feedback to create a light breeze across one’s fingertips; grounding therapy is centered on sound; and movement therapy projects AI generative visuals that respond to a visitor’s gestures as they move through space.

In each gallery, staff members role-played as members of a spaceship crew, offering contextual cues and narrative framing. Their tone, script, and costuming significantly heightened the sense of presence and emotional engagement (Figure 9).

The first three stops were guided, after which visitors were encouraged to explore other exhibition themes at their own pace—striking a thoughtful balance between structure and personal discovery.

Before leaving, I purchased Imagine Design Execute: Inside the Museum of the Future, a book that provides insight into the museum’s conceptual foundations. Its central aim is to foster a sense of shared imagination and community, extending visitors’ experience beyond the exhibition floors and into broader discourse on what futures we collectively design.

Cultivating Pi-shaped designers in an era of cross-disciplinary practice

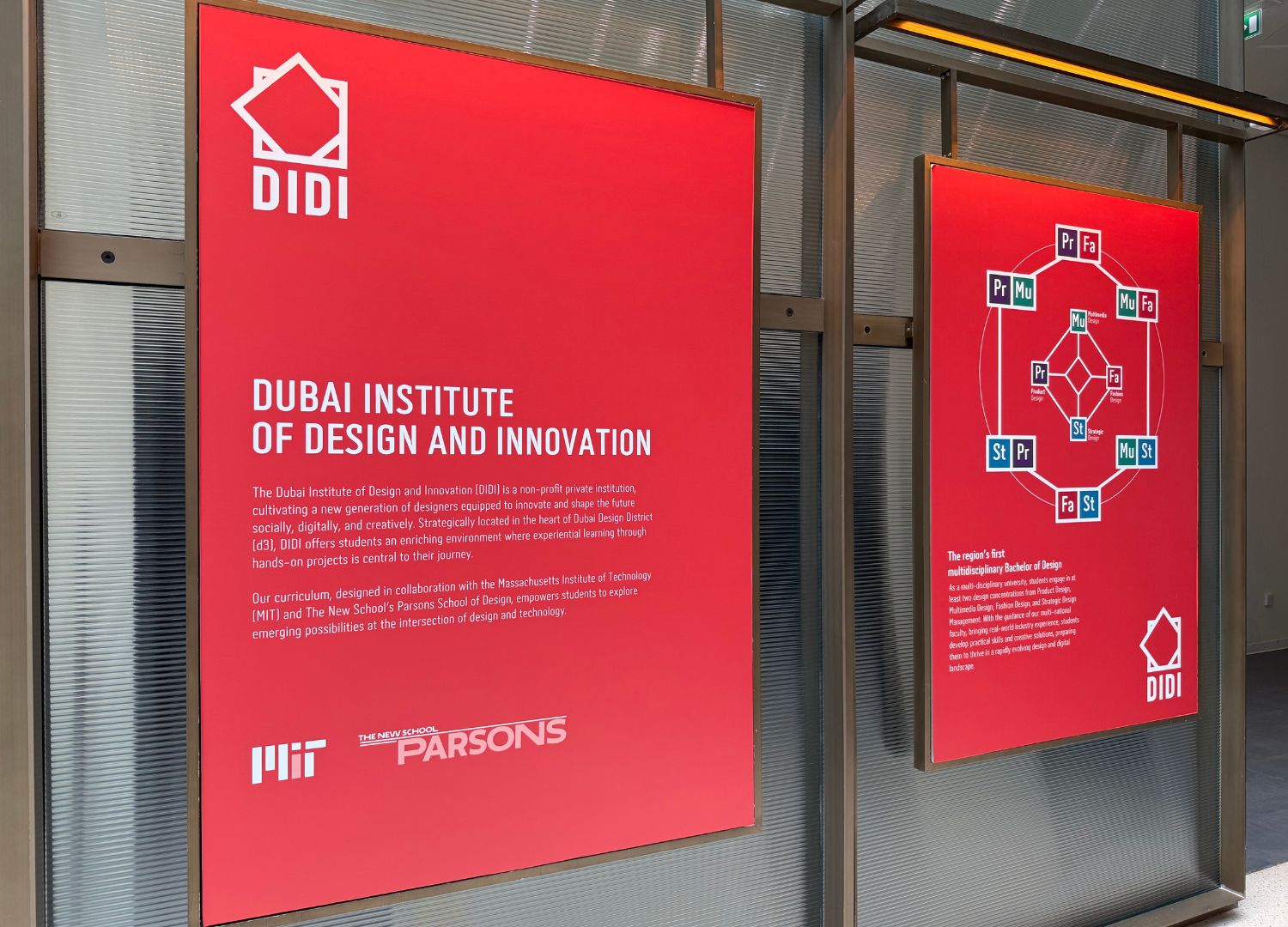

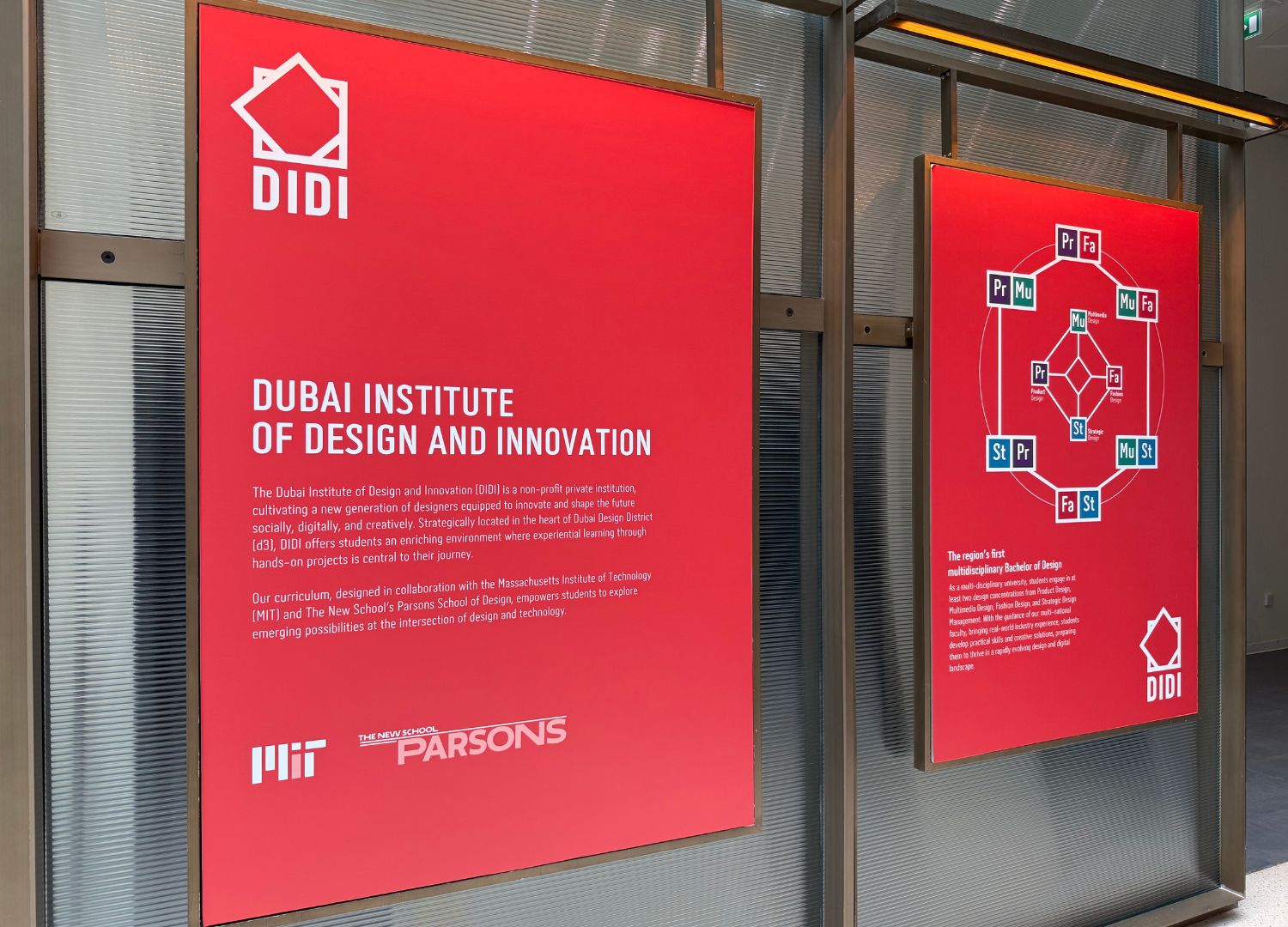

On my last day, while wandering through the Dubai Design Week campus in the D3 district, I came across an education forum hosted by the Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation (DIDI).

DIDI is a non-profit private institution dedicated to cultivating a new generation of designers who can shape the future socially, digitally, and creatively. Its curriculum, developed in collaboration with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Parsons School of Design at The New School, encourages students to explore emerging possibilities at the intersection of design and technology.

I was particularly intrigued by DIDI’s multidisciplinary Bachelor of Design program, in which students customize their education by combining two concentrations from four domains: Product Design, Multimedia Design, Fashion Design, and Strategic Design Management (Figure 10).

A central ambition of DIDI is to cultivate “Pi-shaped” designers, individuals who develop depth in two complementary disciplines and can move fluidly across boundaries. In an era shaped by artificial intelligence (AI), computational design, and rapidly evolving knowledge systems, the capacity to work across domains while continually learning has become fundamental to contemporary design practice.

This aligns with four dimensions I outlined in my perspective paper published by Design Studies (2025), reframing design as:

- Immersive Experience—shifting from artifacts to situated experiences

- Evolving Computational Capability—redefining AI from artificial to anticipatory intelligence

- Relational Tension—balancing ego-driven authorship with empathy-driven action

- Expanding Field—integrating cross- and trans-disciplinary knowledge

These dimensions position designers as connectors, curators, and co-creators of meaning—not only makers of things but stewards of shared futures.

Learning from Dubai: Design, Longevity, and Cross-Disciplinary Practice

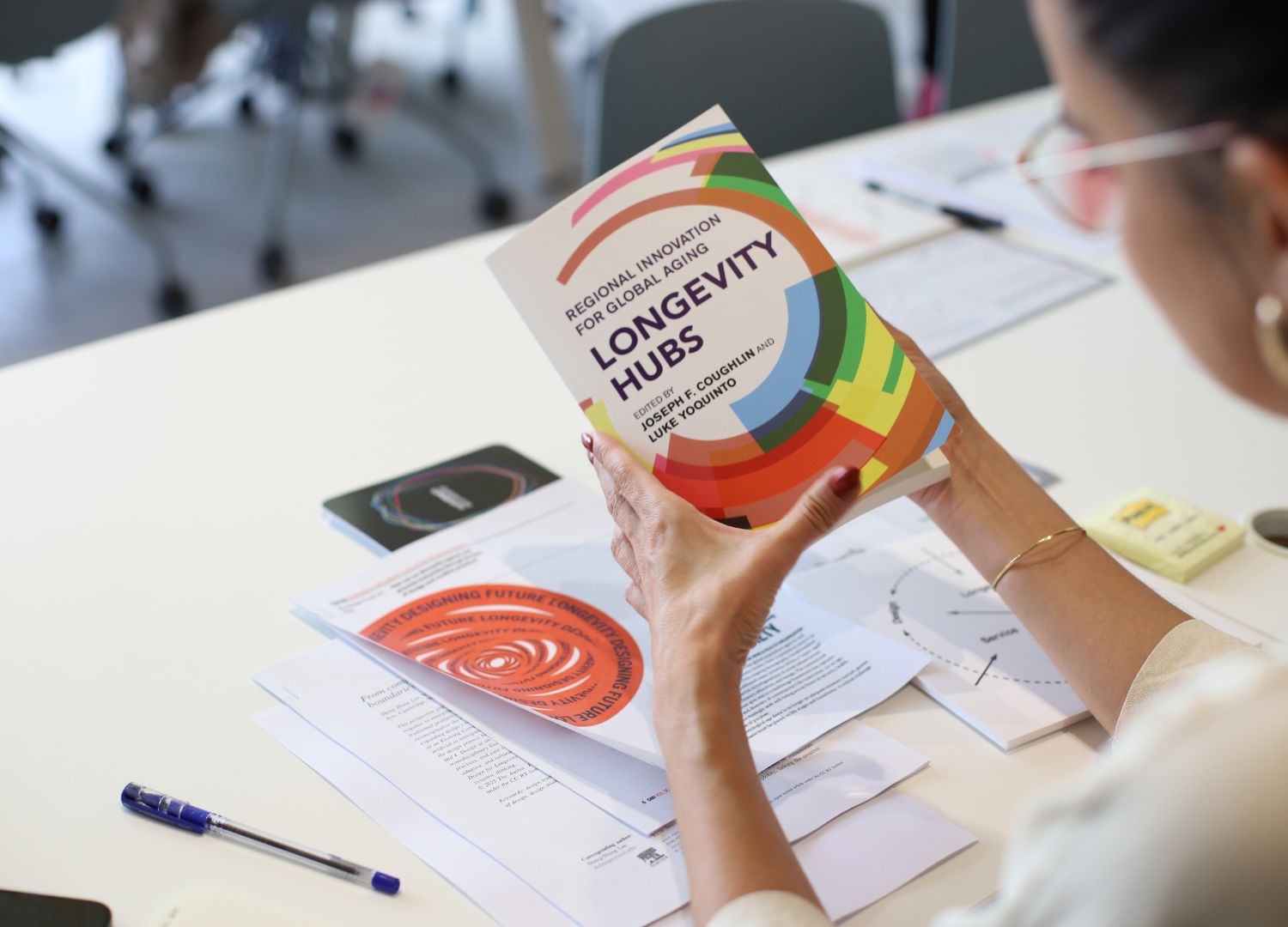

Throughout the participatory workshop, the museum visit, and conversations with educators in Dubai, I gained deeper insights into the concept of Design for Longevity (D4L), which has become the central focus of my current research.

D4L is not merely a framework or methodology. Rather, it is a practice of reorienting how we perceive time, interaction, and future possibilities—shaping a collective vision for navigating complex, multi-generational cultures, work environments, and societies (Figure 11).

The embodied photogrammetry exercise demonstrated how movement and close observation can reshape our understanding of aging and place, positioning longevity as something experienced through everyday encounters rather than measured solely in years.

The Museum of the Future illustrated how environments can be intentionally choreographed to spark imagination, encouraging visitors to feel, speculate, and co-construct narratives about what lies ahead (Figure 12).

Meanwhile, the discussion around cultivating Pi-shaped designers reinforced that contemporary design education must develop both depth and range. Designers require foundational craft and process skills, but also the adaptability to navigate across various scales, disciplines, and modes of collaboration—what Simon Sinek, an author and leadership expert, refers to as human skills.

Together, these experiences during Dubai Design Week highlight a shared imperative: to design educational, urban, and experiential environments that foster curiosity, empathy, and continuous learning.

D4L is not only about planning for an aging society, but also about shaping conditions that allow people of all ages to feel connected, capable, and empowered to shape their own futures.

Dubai’s ambition and openness to experimentation provided a fertile ground to explore these ideas. The work ahead lies in translating these insights into design practices that support more inclusive, multigenerational, and imaginative urban futures.

Acknowledgement

The author extends heartfelt thanks to Dubai Design Week, Caoimhe Jane Reynolds, Rasha Padiyath, Mivan Makia, and Ife Adedeji for their support, and to Professor Sofie Hodara, MIT AgeLab, the d-mix lab, and all workshop participants for their invaluable contributions. Appreciation is also given to DesignWanted for partnering to publish this work.

Reference