The groundscape challenges faced by some of the tallest buildings in the world

John Wong gives us an insight into what are the groundscape challenges faced by some of the tallest buildings in the world. How difficult is it to find a human-scaled aesthetic and experience for the visitors? And how can leaders improve urbanization today?

Meticulous, zealous, inspirational, and true pioneer are some of the words that can describe John Wong. Having over 44 years of experience as a landscape architect, John has directed an array of both micro and macro projects in North America, the Middle East, and Asia and led over 150 campus improvement projects at Stanford University and mentored numerous students.

As a firm believer in teamwork, John emphasizes on collaborating with the best minds in the design field “to push the envelope, raise the bar”. The unprecedented perspective of his designs along with his leadership competency has led him and his team to design the groundscapes for 12 of the tallest buildings in the world- including the Burj Khalifa, the Shanghai tower and at present the Jeddha Tower which will be the tallest building in the world at 1km (3281ft) in height! With a remarkable educational background as an MLA graduate in Urban Design from Harvard University, John shares the importance of an on-site education compared to online classes.

Since his first encounter in landscape architecture along with SWA Group in 1976, John has not only experienced the metamorphosis in this field but also braved all challenges – be it technical, commercial, or humane.

DesignWanted had the opportunity to interview John Wong and perceive his awe-inspiring journey, learn more about the four essential elements that provide a foundation for good projects, and how the landscape can connect with the world!

Who is John Wong? How did your journey in Architecture and Design begin?

John Wong:

“I’m a landscape architect and passionate about design as a way of making people’s lives better—through the creation of places that are impactful, beautiful, and useful. Design can change people’s lives and the way they look at the world.

My family expected me to be a doctor or an engineer. I was born in Hong Kong and my family moved to the US when I was ten. I didn’t speak a word of English when I arrived here in the sixth grade, so I always felt like I started from behind. When I was in high school I took a drafting class and excelled. My teacher thought I had beautiful line work, and encouraged me to explore architecture, which is what I majored in at UC Berkeley as an undergraduate.

I remember very clearly when my interest shifted to landscape architecture. Peter Walker delivered a guest lecture to the students, and he showed these big plazas and large corporate centers he designed. The scale and character of his work were so impressive, and I was also inspired by his motivation to make a better world. The very next day, I went to see my advisor Michael Laurie and switch to landscape architecture.

If my parents thought architecture was a niche profession, at least they could liken it to engineering; they were confounded by my shift to landscape architecture and thought that I was running away from being a doctor.

Peter Walker inspired me initially and went on to become central to my development as a landscape architect. He has been my mentor, my teacher, my boss, and ultimately (many years later) my business partner at SWA Group. (Peter is one of the founding partners of SWA Group along with Hideo Sasaki.)

When I graduated with honors from UC Berkeley, I was selected for the SWA Group summer student program. This is an annual internship program the firm hosts to engage the firm’s professionals and a small number of promising students (who compete for the spots) on a real-world problem, pro-bono, and then spend the summer working on projects at the firm. Peter Walker led the program that year – it was 1974 – and he worked us very hard. It was exhilarating and exhausting. At the end of the summer, I was offered a job at the firm and worked for SWA Group for about a year before a terrible recession hit. It was far worse than today’s pandemic in terms of its immediate impact: within three short weeks, the firm went from employing 85 people to 30. SWA Group connected me with Pod, a landscape architecture firm in Irvine, California that was run by friends of SWA Group principals Bill Calloway and Dick Law, and I worked there for a couple of years, where I learned how to detail.

I decided to go to graduate school and got into the GSD at Harvard, where Pete was chairman. On day one, when I arrived, there was a note from Pete pinned to the door of my dorm room, inviting me for a drink and challenging me to start SWA Group “East” with him, in which I’d hold down the business of the office, hire and manage staff, while he would teach and bring in work. I worked there for seven years and became the youngest partner at age 27 (Martha Schwartz even joined us after she came to Harvard as a student).

My tenure at SWA Group East came to an end in 1981, when I won the Rome Prize and spent a year at the American Academy. When I returned to the United State and to SWA Group, Pete implored me to work with him as the landscape architect for SOM in Chicago: we designed the landscape for all their buildings. At the time, everything was hand-drawn, and we would sometimes present up to five or six projects at a time. You learn fast. I still work today with some of the SOM designers I met at that time.”

Your journey at SWA Group began 44 years ago in 1976! Since then you have also worked on large-scaled planning and design of towns and new communities. Can you take us through your design process? What are the key aspects to keep in mind when managing a project?

John Wong:

“You asked about the design process, especially for large projects. I learned a lot about design from Pete Walker, Kalvin Platt, Jim Reeves, and others. And I learned a lot about business on my own. To be a good professional, it’s important to know about both. On the business side, you need to be sure you get paid, that you can build what you design and deliver on time, and that you can manage a team of people, including yourself!

In my experience, four essential elements provide a foundation for good projects:

- Client

- Program

- Site

- Budget

You need a good grasp of all four elements, by asking a lot of questions and engaging in a lot of listening. The synthesis of that inquiry leads to a strong idea, and that’s where design starts. If there’s an issue, I always return to those four elements. As for leading projects, I don’t micro-manage. My approach is to put together a trusted design team, and then keep them working together, building on the idea, and moving in the same direction. I like to lead multiple projects at the same time. It’s not linear thinking.”

In the last two decades, SWA Group has led more than 150 campus improvement projects at some of the most prestigious universities in the world like Stanford. How do you suggest design students make the most from online-classes given that an on-site experience during a project is essential?

John Wong:

“What distinguishes a great campus, like Stanford’s, is the public realm—the connective space between buildings where people encounter each other and come together. It takes years to build a great campus, and it’s been a satisfying experience working with some of the best professionals in the world at Stanford, both on the staff and the consulting side. Olmsted envisioned a strong landscape framework for the campus, and the university has been guided by it over time. There were some buildings that were badly sited in the 1950s and 60s and we’ve worked around that to stitch the campus back together, creating outdoor spaces that give character and shape experience. I’ve enjoyed collaborating with leaders there like David Neuman, who appreciate excellent architecture but also understand the value of landscape to facilitate connections, both physically and metaphorically.

The experience of the campus is so important to the educational experience, so I hope that today’s students who are impacted by the pandemic will be back on campus before too long. While virtual learning is probably here to stay, students also need on-site experience. Whether it’s circulation through the campus on foot or bike or gathering with others in a quad, students need those outdoor campus places to engage. They are so important to the culture. Colleges and universities in California and other temperate climates also have the opportunity to host classes outside.”

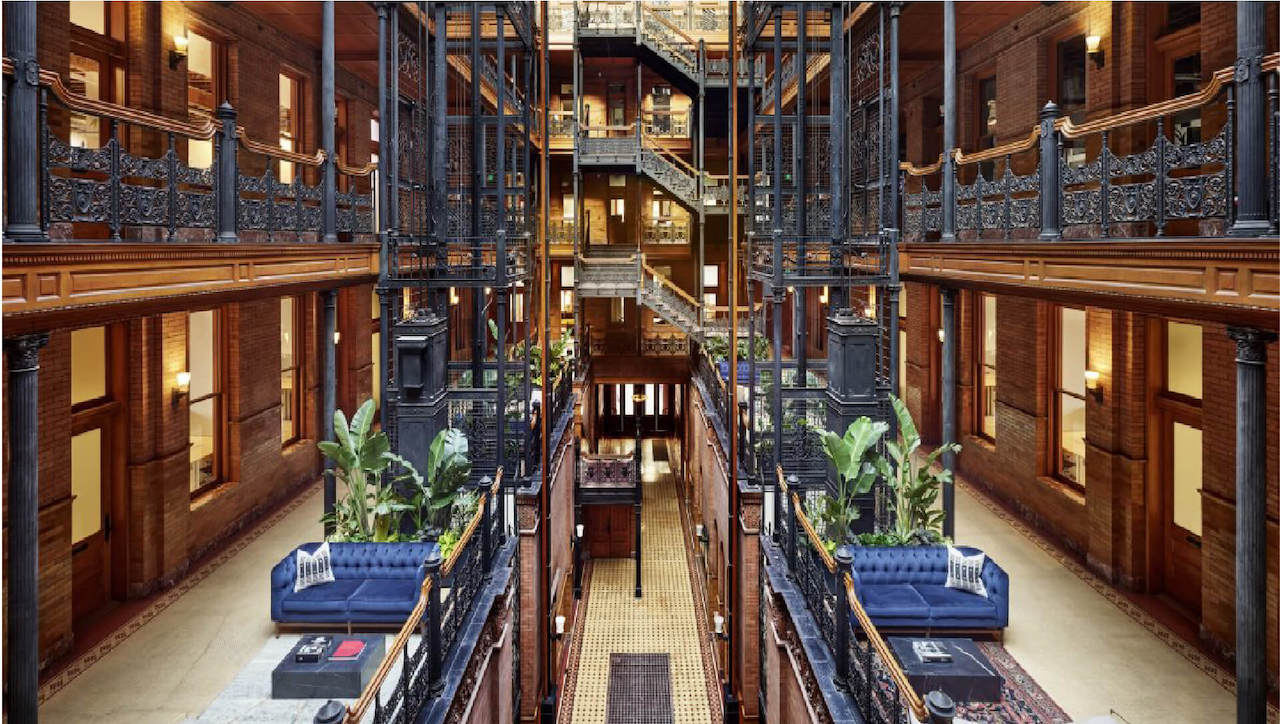

Designing the groundscapes for 12 out of the 100 tallest buildings in the world including The BurjKhalifa, The Shanghai Tower and The Cayan Tower is truly inspiring. What is your driving force? Could you share with us some of the challenges faced during the design process of these gigantic projects?

John Wong:

“Designing groundscapes for tall buildings wasn’t something I sought out; it was an outgrowth of relationships with talented architects, many of whom I met early in my career when SWA Group was the landscape architect for SOM. At one point, I think I had thirty projects in Chicago with SOM. Bruce Graham was a prolific architect of high rise buildings and had a staff of architects working for him, who then went on later in their careers to design several of the towers you mention. So the driving force for my work on these projects is really about working relationships with people. I’m currently working with Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architects on the Jeddah Tower in Jeddah that will be the tallest building in the world when it’s completed.

There are lots of challenges working on the groundscape for these projects, ranging from sophisticated building design and technical considerations to the wind created by the building to all the human egos involved. The buildings themselves are huge and contain an entire city in vertical form, so one of the groundscape challenges is to find a human-scaled aesthetic and experience for people who come to the building, and which also is pleasing when viewed from above (as many visitors see it). All the projects are built on structure, too, so there are challenges of how to artfully accommodate utilities and life safety exits at the ground.

The architects tell you where they will be, but we have to figure out what to do with them. To give you an idea of scale, the BurjKhalifa is a 27-acre site, seventy percent of which is on parking and mechanical structures. Water and wind also pose challenges for what kind of plantings can be accommodated. And then there is the question of how the grounds can add value to the surrounding cityscape when most of what people need is within the building.”

As we see overpopulation and climate change is affecting the infrastructure of our cities, what is your perspective on how leaders and designers can assist in improving “urbanization”?

John Wong:

“Most people live in cities today, and urbanization will continue at the urban edges. What people are discovering now, during this pandemic, is the importance of outdoor spaces—the public realm. People are rediscovering parks, and how essential these spaces are to a good quality of life. I live in San Francisco, and places like Golden Gate Park, the Presidio, and Land’s End are full of people. It’s great if you live nearby, but what’s missing in many cities is easy to access to parks.

What cities can and are doing right now is to close some streets to car traffic, and allow a pedestrian right of way. It’s an inexpensive and great way to get people outside safely and enable better connections to cities’ parks. In New York City, it would be great if you could close a street for most of the day –- say 9:00 am to 8:00 pm – and allow a pedestrian thoroughfare from Battery Park to the Bronx. You would have deliveries and services operating at night and early morning and still permit day time emergency vehicle access if it was needed. It would open up a different way of experiencing the city, and leaders could do it tomorrow at very little cost. Cities could strategically and temporarily close and capture streets for open space.

As cities continue to expand, I would encourage leaders to provide a framework for that growth that has open space at its core. That’s what makes for great cities.”

The year 2020 has put us all “thinking outside the box” with our work. What are some of the modifications you are implying with regard to the complete design process and efficiently assisting your clients?

John Wong:

“Thinking outside the box is really about being newly observant about the world, finding connections you haven’t thought of before and solving for new kinds of issues—climate change, environmental resilience, and social equity all of which are so important. And there are some enduring basics. Everyone appreciates beauty, and the world could use more of that. I still find the core concerns of client, program, site, and budget as useful touchstones when working on projects.”

What are the future goals of SWA/BALSLEY? Are there any upcoming projects we can keep an eye out for?

John Wong:

“SWA/Balsley is committed to helping cities create a robust and impactful public realm. Tom Balsley has a legacy of creating public space in New York, and we want to continue that in New York and beyond—working for both public and private clients. Outdoor spaces are so important to public health, which is something we are all more aware of these days, and cities need to improve the quality of the public realm and access to it. Design can change profoundly change people’s daily experience of their environment, and offer benefits that are immediate and enduring. That’s where we are focused as a practice, and it motivates us as designers.

Upcoming projects include EXPO2020 in Dubai, where we designed the entire public realm to showcase how a landscape can connect the world. The opening was postponed a year until October 2021. We are working on a waterfront park – Mandela Park – to serve a diverse community in Rotterdam, Netherlands. I’m also working on an iconic destination project for the Bank of China in Shanghai at the new Free Trade Zone, and the design of a new Science City, a satellite city to Shanghai that will focus on innovation and technology.”