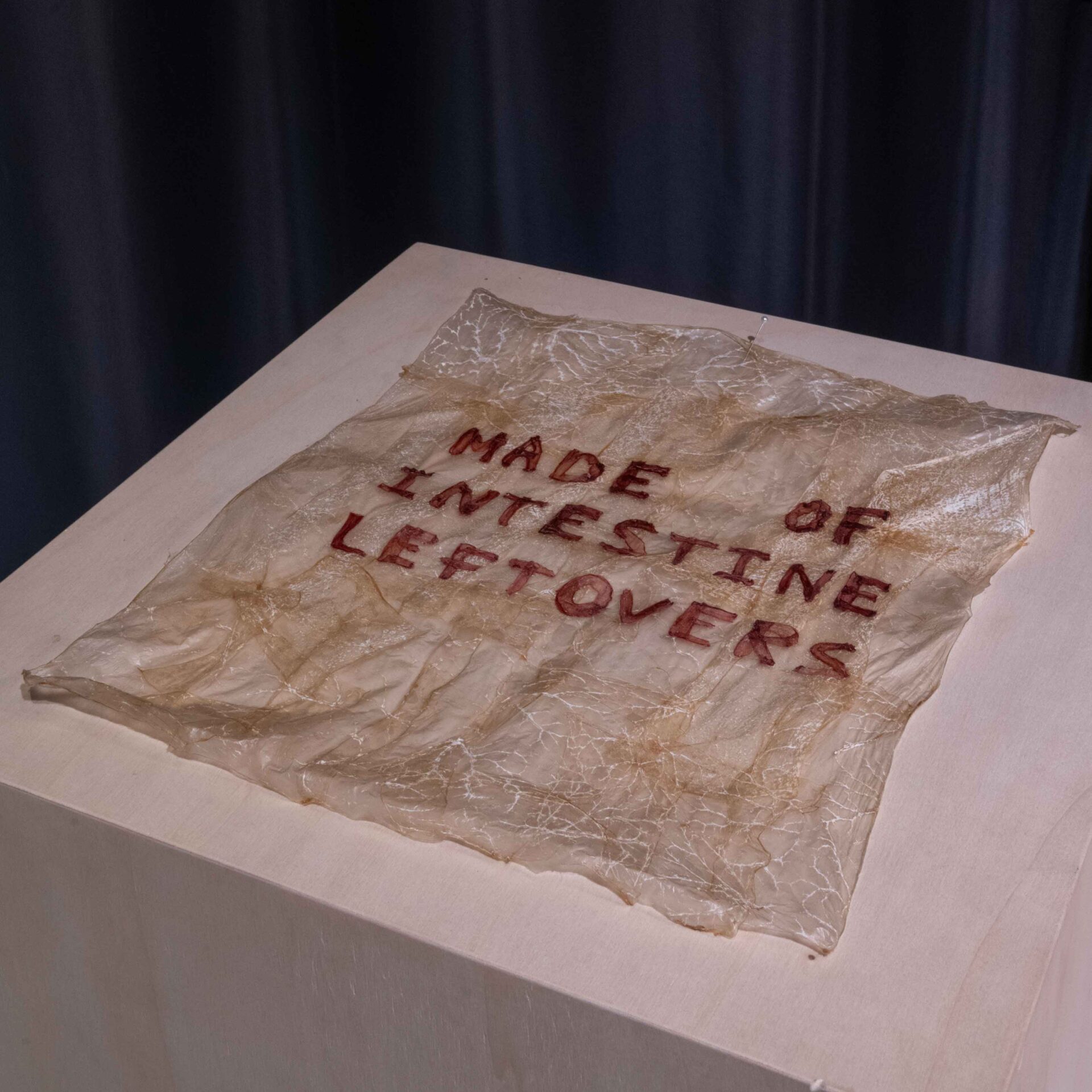

Made with an unexpected material of animal origin, these works lead us to question the conventional notion of waste

Through the hands of Thibault Philip, animal industry waste is reborn as works of striking complexity; humble materials transformed into chandeliers, installations, and sculptures that invite us to rethink waste

Thibault Philip is a French designer who works with a material that, at first glance, may evoke a sense of disgust: animal intestine recovered from industrial waste. A feeling of repulsion that coexists with the sense of wonder inspired by his works: lamps, installations, and sculptures with complex textures, creations that speak equally to the worlds of art and design.

But let’s take a step back. As controversial and delicate as it may seem, Thibault’s project raises an important reflection on a highly relevant issue today: production waste. We are generally accustomed to consuming goods and products with great ease, discarding their remnants without ever questioning their future destination, often even when these goods and products have not truly reached the end of their usefulness.

Much of what we throw away is not the result of an object’s true exhaustion, but of a cultural mindset shaped by convenience, speed, and distance from the origins of the materials we consume. Design, in this context, becomes more than an aesthetic or functional discipline: it becomes a cultural agent capable of reshaping our perception of matter.Thibault’s practice, by contrast, refers to a production system that shows greater respect for materials and the planet’s resources. Inspired by ancient cultures, he grounds his work in a concept of production in which waste is not seen as such, but as an additional raw material with infinite potential.

Gallery

Open full width

Open full width

“In my work, I am not constantly looking for new things; I am more interested in consistency and precision, knowledge and depth,” Thibault tells us at one point in this interview.

Such an approach requires an in-depth study of materials and a careful research process—one that involves setbacks, yet remains profoundly intentional and aware. The use of the intestine is not a random choice, but a considered and deliberate one, supported by collaboration with scientists. This allows Thibault to gain a deep understanding of the material he works with and to fully exploit its technical properties, avoiding the unnecessary use of additional materials that would only generate further waste.

This industrial by-product is thus reclaimed and transformed by Thibault into ceiling lamps and large-scale installations that, through their extraordinary presence and aesthetic, deconstruct the common negative misperception of this natural element. The process itself is simple: salt to preserve the material, water to rinse it, and natural dyes (black is obtained with squid ink, orange with poppy, blue with nila, an ochre used by the Tuaregs, yellow with cumin, and red with madder root).

His practice is not about producing new, sterile, or purposeless objects, but meaningful works, projects that speak of a return to a way of living and producing that views waste not as a problem to be disposed of, but as a resource to be understood, valued, and reimagined. It is a practice that does not chase novelty for its own sake, but rather dives curiously into what already exists, into what we have not yet fully explored or understood.

In this interview, Thibault shares his work from every perspective: practical, ethical, philosophical, and artistic. I’ll let him take it from here.

Tell us a little about yourself. Who are you, what do you do, and what has your journey been like so far?

Thibault Philip:

My name is Thibault Philip and I am a 29-year-old French designer and artist. My background is a mix of EESAB in Rennes, where I earned my master’s degree, the University of Arts in Poznan, and internships with Marlène Huissoud and, above all, Nacho Carbonell. My approach as a designer tends towards total radicalism in terms of materials and a quest for meaning and narrative in my objects. I want them to be unique and alive. For the past five years, I have been working on the reuse of food industry offcuts, especially intestines that are the wrong size or have holes.

The aim of this work is to create objects that question the relationship between humanity and animality while highlighting our cultural heritage. One of my goals is to return to the craftsmanship of the past through the industrial waste of the present. Taking a radical and manifest stance, I work with scientists to gain an in-depth understanding of the materials I use. This process allows me to move from the micro to the macro by exploiting the technical properties of the materials. For example, the proteins in intestines bio-weld themselves, meaning I never have to use glue or resin.

Your creations are extraordinarily fascinating from an aesthetic point of view. They are, in every sense, beautiful pieces that stand halfway between art and design. And yet, they originate from the manipulation of a material, an animal intestine, that can instinctively provoke a sense of repulsion. Have you ever reflected on this dichotomy? If so, what does it mean to you?

Thibault Philip:

Thank you for this important question. The fact that we are leaving environments connected to living things and becoming more and more urban and consumer-oriented cuts us off, as humans, from a real perception of the world. In the past, the proximity between humans and the environment allowed for a better understanding of it, and therefore, better knowledge. The crafts of ancient populations are an example of this, particularly their ability to take technical advantage of all the materials around them.

One of my goals as a designer is to break down the false perceptions we have of intestines in order to reveal their aesthetic and technical value. The dichotomy between aesthetics and disgust—this gap—is precisely a manifestation of our misperception of intestines. We think they are horrible and disgusting, when in fact they are a fine, translucent material that is incredibly resistant and has an authentic and unique pattern. Many ancient civilizations, such as the Inuit, understood the value of this material, and in my work, I seek to offer a more accurate interpretation of the living world.

Your works are also visually complex. A first glance is never enough to fully grasp their structure, subtle color variations, texture, and form. Does their appearance, in some way, dialogue with their material origin? Or do you draw inspiration elsewhere?

Thibault Philip:

The appearance of my objects is inseparable from their biological essence. I take the concept of organic design in the most pragmatic way possible, by using organs. The technical richness of this material allows it to be woven into thread, stretched into sheets, accumulated to achieve rigidity, but also formed into tubes, plates, and many other elements. Using this vocabulary of form, I define a direction for my objects, always taking into account the behavior of the material, whether in terms of how it dries or the fact that the pattern of the material changes each time, making every piece unique (see the differentiated series by Gaetano Pesce, one of my thought leaders).

In my way of working, I am more interested in collaborating with the material than in forcing it to become something else. I hope that the resulting pieces reflect this osmosis. For me, the biological world is a realm of infinite formal freedom, whose complexity of patterns and textures is inexhaustible. This is also what I try to convey in my work: the timeless aesthetics of the living.

Where did the idea of giving new value and function to discarded animal intestines come from?

Thibault Philip:

Initially, while doing my master’s degree, I was tired of mimicking the living world with unsuitable materials (resin, silicone, molten metals, etc.). I wanted to adopt a more authentic approach that was closer to my fascination with the living. After exploring various materials (bioplastic, algae, mycelium), I researched the use of animals and discovered that they are found in everything: hemoglobin in cigarette filters, protein in cellular concrete, collagen in electronic compounds — the list is huge. This use generates enormous production, which in turn produces enormous amounts of waste.

For the past five years, I have been combining the two through scraps from a quality control and quotation company specializing in natural intestines, called GBB Boyaux Bretons. This company embodies craftsmanship — but in the food sector — in order to handle the materials as carefully as possible and detect holes and defects. It is not a slaughterhouse but a casing company that operates within a short supply chain and sources only from Europe. They provide me with intestines that are not the right size or have holes in them — the ones that are usually thrown away. I was then able to analyze this material with the National Center for Scientific Research, which allowed me to understand that the proteins in the material enable it to bio-weld itself as it dries.

What does this experimentation mean to you – beyond the act of creating artworks/ design objects?

Thibault Philip:

Endless research means constant discovery, which is a source of joy and challenge. There is also the pleasure of engaging in dialogue with circles outside the worlds of art and design; scientists have boundless curiosity and a playful spirit. I am also fortunate to be able to talk about agricultural and farming communities through my work, which helps raise the profile of people such as the workers at the company that grades and quality-controls intestines, where I source my materials.

I also try to show that the past can serve as an example for the future — that the ways of doing things in the past were virtuous, taking as an example those populations who lived without wasting any part of the animals. I also try to show that craftsmanship can reinvent itself through design; that despite a biased and demeaning perception, the aesthetics of the living are everywhere, and that attitudes can change. My work reflects my stance: radical, as I work only with this material, without adding glue or resin; and manifest, because I try to reveal both the technical values (the proteins that bind together, the resistance, the diversity of forms) and the aesthetic values of this material.

We know that part of your research was inspired by the work of Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma. Could you tell us more about that influence?

Thibault Philip:

I had previously researched the use of animals and knew it to be intense and widespread. Christien’s book made this understanding even more profound and far-reaching. I use this book to illustrate my point, and it is crucial because it clearly shows that our world is an interconnection of materials. It also provides a better understanding of the systems established in production.

There is a wide range of products made from pigs, including plaster, cigarettes, concrete, paint, sandpaper, ceramics, and more. This diversity shows that human comfort is built on the use of animals. Although the book focuses only on pigs, it is important to note that the same uses exist for other animals, such as bovines and ovines.

To what extent is your work truly connected to the principles of circularity and resource optimization?

Thibault Philip:

Beyond reusing offcuts, my work uses design to demonstrate another way of doing things while delving deeper into the material to find, use, and showcase the technical values of the living. The aim is also to work within a short supply chain, with a company located 30 minutes from my studio, and to remain within Europe, with the most distant collaborator based in Germany.

Research into materials takes time. While art and design are the visible parts of my work, another part is progressing behind the scenes with scientists and other methods of shaping the material. This aspect is more related to the concepts of resource optimization and the replacement of polluting materials with those derived from biological waste, such as intestines, but it still needs time before it can be shared widely.

This year, you took part in Dutch Design Week, whose focus is well known to revolve around material experimentation and responsible design, presenting a new and unreleased work. Could you tell us about this project? How did it engage with the 2025 theme, “Past. Present. Possible”?

Thibault Philip:

With all its boldness, madness, and breaking down of barriers, Dutch Design Week is a key moment in my practice. There, I understood that design could be much more than what my limited perception as a young student had allowed me to see. From the beginning, my work as a designer has been based on objects that are formally calm and quiet. Returning to Eindhoven for the exhibition “Basic Instinct: Making With,” which will run until April 2026 at Kazerne, is a way of going back to my roots and starting a new chapter.

So I chose to be less restrained, to be more accepting and expressive, to show my language, and to create an important piece that resembles me more. Louvanes, named after the three interns who assisted me — Louis, Eva, and Inès — is a chandelier that explodes while remaining connected, a biological chaos emerging from a methodical process. There was almost no drawing at the beginning; I simply had an idea of what the result could be, from weaving to dyeing, from combining shapes to stretching the material. I wanted this chandelier to represent the possibilities of intestines in terms of aesthetics, structure, technique, shape, and color. My entire project converges on the theme of Dutch Design Week: the crafts of the past resurfacing from the ruins of today’s industrial system to create new possibilities for tomorrow in terms of aesthetics, radicalism, and the technical richness of the material.

How do you imagine your work evolving in the future? Do you think there will come a time when animal intestines will begin to interact with other types of raw materials? Are new experiments already underway?

Thibault Philip:

In my work, I am not constantly looking for new things; I am more interested in consistency and precision, knowledge and depth. The advantage of gut offcuts lies in the diversity of results that can be achieved. For the moment, I want to push the boundaries of what is possible even further and work more closely with scientists in order to guide the material toward new applications. From a design perspective, I want to make the shapes even more complex, more profound, and, in a sense, crazier — free from all constraints.

However, the material has its limits, particularly in terms of lightness. The goal is to overcome this limitation by hybridizing it with another material that adds weight and mass but shares the same characteristics as intestinal waste: no glue, no resin, and derived from living organisms. Research is currently underway in the studio on strains of mycelium that could meet these criteria.

In talking with Thibault, one reflection emerges: being considered ‘waste’ is not something inherent to specific natural or industrial elements — like a rotten apple, an empty can, a banana peel, and so on. It is a label we assign, out of ignorance or lack of means, to things that in reality “hide” infinite potential and therefore infinite possible uses. These approaches offer new perspectives on managing an issue we can no longer ignore: the handling of production waste.