An inquiry on research and business in Architecture, by MuDD Architects

MuDD Architects were invited by Designwanted to write a series of articles on the theme of Research and Business in Architecture, investigating how these two aspects intertwine and contrapose each other

We are thrilled by this writing opportunity as we have developed our own projects in both academia and industry environments. In addition, for MuDD Architects company to be viable as a business we need to constantly evolve our technologies and projects in close proximity with academia to remain competitive in the market.

There is a general trend from universities and research labs to intend to create new relationships with industry and immediate use of new technologies, new processes, or new materials developed by students to be used directly into real-life projects to be built. But some ethical questions emerge. Should academia do business? Should the projects developed for clients be used to advance research agendas?

We start this series on articles on Research vs Business in Architecture with the point of view of two engineers who are at the forefront of innovative construction engineering solutions.

Edoardo Tubuzzi director at AKT II London and Diederik Veenendaal from Summum Engineering in Rotterdam, who both worked with MuDD for the Terramia Drone Spray project in Milan.

Edoardo Tibuzzi AKT II London

Is there any relatively new material that you use in your projects that was initially developed in an academic environment?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“At AKTII, research in practice and in academia has been a constant focus since the inception of the company: we are constantly involved in researching new possibilities. In a small installation recently completed, we have implemented a patented system originally developed by the Swiss company Generelli SA and the Italian research team New Fundamentals from the Polytechnic of Bari, involving carbon fiber reinforced stone.”

Do you consider new processes more important than new materials?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“Materials are fundamental to our industry, but the only “new material” discovered recently that could have a big impact on our industry is Graphene which has been dubbed “the new steel”.

Although the first useful applications are starting to emerge (self-cleaning concrete, corrosion-proof steel), we will probably have to wait a bit longer before we can see the results of the current researches on its potential benefits to our industry.”

Have you ever been able to patent a new technique or material or combination of both through one of your client’s projects, without any academic involvement?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“No, but have worked with several new patented material solutions that have been achieved in collaboration with academia and/or industry. As an example, we used a new GFRP compound for the 2016 Serpentine Pavillion with BIG Architects.”

Among your clients, which one was mostly willing to take a risk for the sake of research and sustainability?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“Research and sustainability are at the top of the agenda of the majority of our clients. We had the luck to work for many major organizations that have pushed timber solutions, DFMA, composite materials, renewables, etc.

Across academic institutions working on new materials and processes, can you think of one, in particular, that is different from the others and that you would like to team up for your next projects?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“There are many academic institutions that have a deep interest in that side of research. We are particularly interested in the influence that big data will have on the way in which we think of new processes and materials. The biggest surprises are coming from the medical research departments and I think that cross-pollination would benefit both sides.”

Do you feel real innovation comes rather from industry or rather from academic research labs?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“If you ask me, I would think that innovation comes from design, wherever that would sit. More often academic research pursues targets that are taking a universal approach, therefore the focus is not on implementing a ready solution.

The industrial Ph.D.’s are now filling that gap, we are involved in several of them and can see the benefit, to focus the research efforts.”

Have you ever had a client complaining that is being used as a “guinea pig”?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“Not really. Every time we have tested an innovative solution it was a deliberate choice of the client and the design team.”

Do academic researchers do business? Should they?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“Many of the academics we collaborate with have their practices and push their research into practice. This is a fundamental part of the process in my own opinion as researching without practical implementation is often not fruitful.”

L’abre Blanc building in Montpellier by Sou Fujimoto and Bosco Verticale in Milan by Studio Boeri have been widely criticized for looking sustainable but employing non-sustainable construction methods: the huge amount of concrete they use is far from any progress in targeting greener solutions. We could call this “the green and the allegory of the green”.

Do you think that academic researchers and the industry are faking the idea of green?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“Our is a complex industry and I think there is a lot of effort now to minimize carbon footprint and impact of our buildings. I think that this is an aspect that needs to be taken into perspective as well. Different buildings have different design lives and adaptability and reuse play a big part in the carbon footprint of a building throughout its service life.

So, in the cases mentioned above, we will know the answer probably in 60-100 years! On our side, we are investing a lot of research time to calibrate our tools to have a better prediction of those parameters leveraging on data-driven design and internal experience.”

Can you briefly talk about the collaboration between your firm AKT II and MuDD Architects for the Terramia Project?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

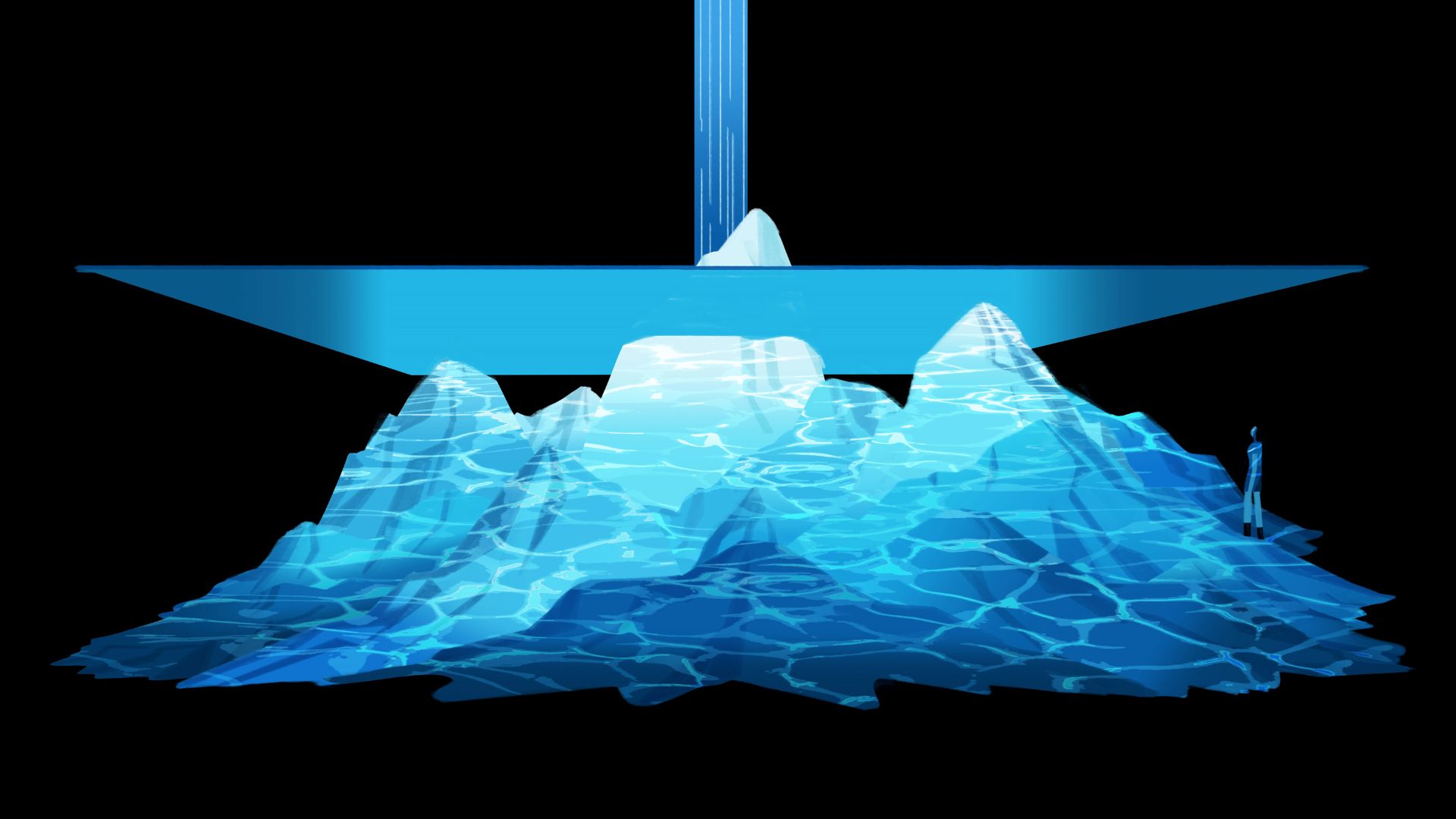

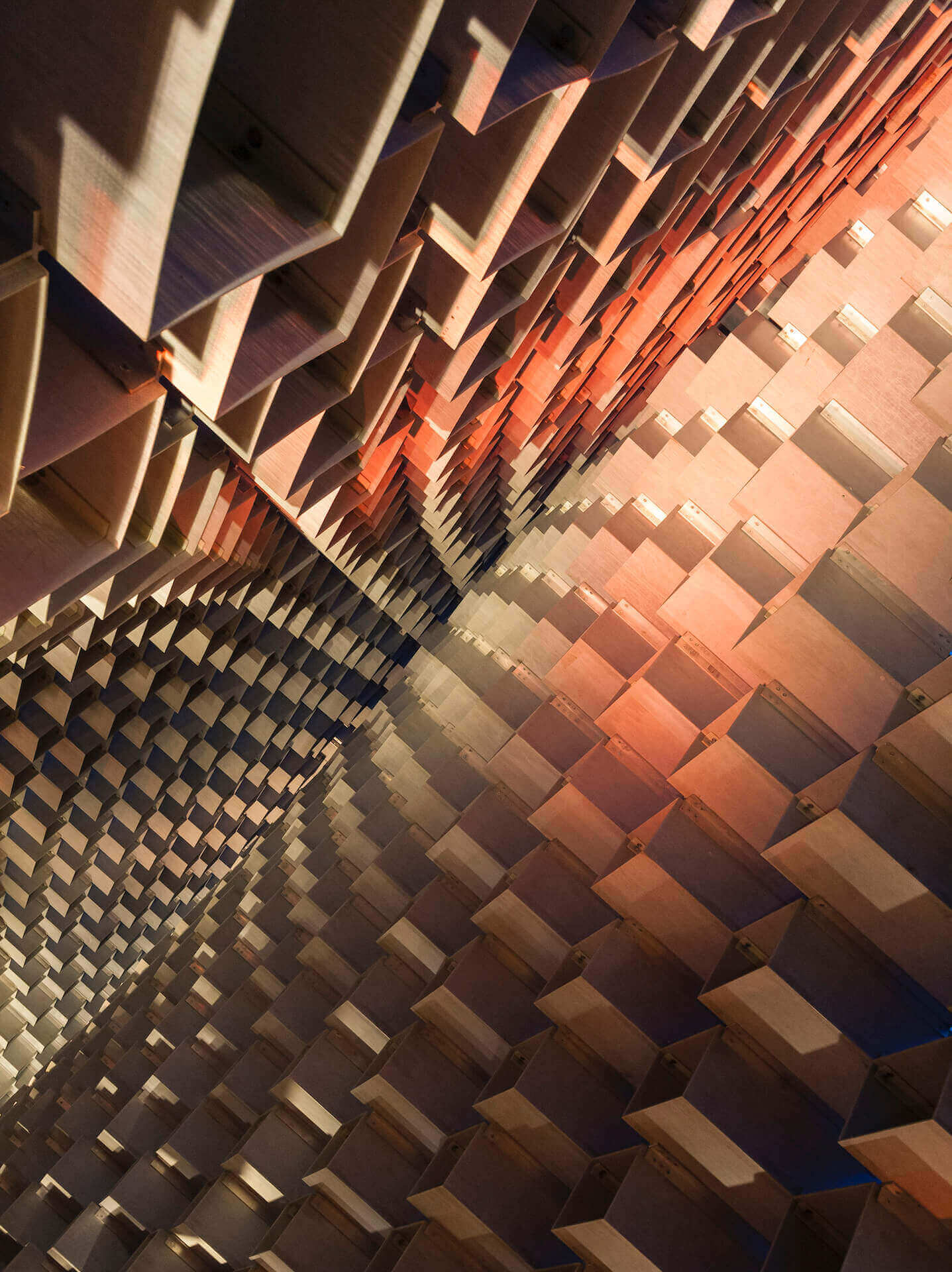

“The Terramia project was an interesting challenge as it added a whole layer of unpredictability to the design process. Working with drones is extremely interesting, especially considering that with a minimum impact they allow access to an area that otherwise would be inaccessible without constructing expensive and intrusive temporary structures.

Another benefit of testing this technology is the fact that the drones being digitally controlled, are inserting a layer in the process which is the enabling of data-driven design.

The Terramia project has pushed the boundaries of digital fabrication, whilst maintaining a very true approach to sustainable challenges and showcasing the importance of selecting the right materials, to make sure we touch the ground lightly and that we use the right tool to design and build. In short, it summarizes all the principles that are at the core of both mine and AKT II design culture.”

Do you find very futuristic research useful for your business? Or do you find more down-to-earth research in construction and architecture directly useful for your projects?

Edoardo Tibuzzi:

“I don’t think there should be a limit, it depends on the problem we are trying to solve. Generally, the biggest outbreaks are the ones that leverage a very simple idea, as an example concrete was discovered by the Romans mixing a mixture of volcanic ash, lime, and seawater.”

Diederik Veenendaal, Summum Engineering

Is there any relatively new material that you use in your projects that was initially developed in an academic environment?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“The Bridge Project involves 3D printed concrete, with much of the material and printing technology originally developed at TU Eindhoven. Other 3D printed concrete projects are from Dutch companies CyBe and Vertico, both of whom have been inspired by academic work as well.

As a material concrete, itself is not new, but 3D printing as a process offers opportunities to use this and other materials more efficiently.”

Do you consider new processes more important than new materials?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“I consider new processes of production and construction, including 3D printing and robotic fabrication to be more important. There has been an excessive reliance on newly developed materials such as plastics and composites to solve society’s problems. Many of these engineered materials are fossil-fuel based, difficult to recycle, and often toxic in their production.

There is increasing interest in the use of natural materials like rammed earth and straw, biobased materials like CLT and laminated bamboo, as well as recycled or even completely circular reused materials.

The main challenge is how to produce and apply these materials efficiently and effectively. With circular materials, how does one use existing supply directly in a new construction, without any downcycling? And how does this constraint influence design? These are more matters of process than material-related itself, in my opinion.”

Do you know any newly built projects that use new materials to result in greater sustainability?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“We are working on optimizing the structural performance and fabrication waste of the Dome of Plants, a design by LOLA Landscape Architects and Nomadic Resorts, which uses engineered, laminated bamboo as its principal structural material. The production of bamboo is one of the top solutions of Project Drawdown to stop global warming.”

[ Read also Bamboo house design & construction ]

Have you ever been able to patent a new technique or material or combination of both through one of your client’s projects without any academic involvement?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“No, patenting is a costly undertaking, and potentially counterproductive, as you become solely responsible for creating a market. I’ve either worked with larger companies or institutes who have patented technology, or I’ve opted to (scientifically) publish the work, such that the intellectual property is shared and can no longer be patented. As an early adopter, this allows you to maintain some advantage while preventing others from patenting it.”

Among your clients, which one was mostly willing to take a risk for the sake of research and sustainability?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“The Dutch government has been financing pilot projects in 3D printing and circular construction. Although those types of projects tend to be overly bureaucratic in their organization and can confuse various interests, the original intent for the funding is to be applauded. The Dutch government aims to achieve a 100% circular construction in 2050.”

Across academic institutions working on new materials and processes, can you think of one, in particular, that is different from the others and that you would like to team up for your next projects?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“The work at ETH Zurich’s Block Research Group, where I obtained my Ph.D., and other chairs at the Institute of Technology in Architecture, is absolutely inspiring and cutting edge, especially at the intersection between structural design, engineering, and digital fabrication. Nearby in Stuttgart, the output of Prof. Achim Menges’ ICD – the pavilions his team builds – boggles the mind.

In terms of circular and waste-based construction, I applaud the efforts of the Structural Xploration Lab at EPFL, led by Prof. Corentin Fivet, and those of Prof. Dirk Hebel and his team at the Karlsruhe Institut für Technologie and the Future Cities Laboratory SEC Singapore. The biobased developments at Prof. Neri Oxman’s MIT Media Lab are often mind-blowing.

Each of these, and many other amazing research groups around the world, do unique work, worthy of much more attention from industry than they are receiving.”

If you want to know more about MIT Media Lab’s work, don’t miss Making Data Matter: MIT Media Lab creates data-sculptures with multi-layered 3D printing.

Do you feel real innovation comes rather from industry or rather from academic research labs?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“Real innovation – in the sense of implemented in construction in a mainstream manner – must come from industry and anything that qualifies does. However, the best ideas that should be used in construction are definitely found in academia. The lack of R&D (due to no funding) in construction is troubling, as is the difficulty that exists in translating scientific knowledge to practice.”

Have you ever had a client complaining that is being used as a “guinea pig”?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“No, but that is because in my case, time spent on innovation was budgeted beforehand, funded by external subsidies, or provided as my own in-kind contribution.”

Are your clients interested in the techniques & innovations that their projects bring to the world or are they most interested in the end result?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“Many public clients, and clients from within the construction industry, have a definite and sincere interest in innovation, albeit for widely different reasons. Private and corporate clients tend to be more focused on the end result with little interest in how it is arrived at, at least in my experience.”

Do academic researchers do business? Should they?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“It is not uncommon for university professors and staff to hold positions in the private sector at the same time. It allows for practice-oriented research and education on the one hand, and knowledge transfer, albeit narrow, on the other. I consider it a good idea in general but can also mean these individuals have extremely busy schedules, making it difficult to focus their energies.”

L’abre Blanc building in Montpellier by Sou Fujimoto and Bosco Verticale in Milan by Studio Boeri have been widely criticized for looking sustainable but employing non-sustainable construction methods: the huge amount of concrete they use is far from any progress in targeting greener solutions. We could call this “the green and the allegory of the green”.

Do you think that academic researchers and the industry are faking the idea of green?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“The problem in science arises with a researcher being forced to frame their core interest in terms of societal issues such as circular economy or global warming, simply to attract funding for their work. This can come off as fake. Instead, there should always be a place and opportunity for undirected, fundamental research, free from societal and corporate interests.

The problem in the industry is that the commercial interests of many individual companies do not align well with sustainable development goals. Terms like “sustainable growth” and “circular concrete” are illogical and incoherent, and part of the overall greenwashing problem.

On a more subtle level, the complexity of the environmental challenge we are faced with has led to a vast array of solutions; methods to design, construct, power, ventilate, insulate, heat and cool our buildings. The resulting discussions and conflicting interests can make it difficult to take a step back, take in the entire problem, and decide on the best strategy moving forward.”

Do you find very futuristic research useful for your business? Or do you find more down-to-earth research in construction and architecture directly useful for your projects?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“We tend to take an agnostic view at the moment, instead of seeking clients and partners that, each in their own way, believe in their approach of changing the future of construction for the better. Doing so helps us to develop our own thoughts and opinions on the matter while working on a cornucopia of cool stuff, like strawbale houses, laminated bamboo domes, 3D printed recycled plastic street furniture, 3D printed concrete bridges and drone-sprayed earthen shells.”

Can you write a few words on your collaborations with MuDD Architects?

Diederik Veenendaal:

“I had met Stephanie Chaltiel at the 2015 IASS Symposium in Hamburg, where we attended each other’s lectures. The concept of using drones to spray natural mortars on lightweight formwork, as a means to create earthen architecture, was such a fresh perspective to me. The drones had more lifting capacity than I thought, and using them for remote building sites, and to spray hard-to-reach areas, reducing the need for scaffolding, was very innovative.

When the Terramia project came around, I was happy to contribute to this next step in her and MuDD Architects’ research. Combining all-natural materials to build three pavilions of significant size was exciting, to say the least. We helped them and CanyaViva developing the design of the pavilions and their construction logic. We also provided parametric modeling and structural engineering, relying on locally sourced bamboo for the main structure.

Gavin Sayers from AKT II reviewed our draft report, offering helpful advice for further improvement. Later, Stephanie invited us to do the parametric design research for possible patterns of a drone-sprayed mural in Brussels. Time and budget were tight on both projects, well below the initial scope and ambitions required.

I’m hoping that future clients recognize the potential of MuDD’s work for future architecture and construction and that further investment will allow them to scale up these concepts and technologies.”